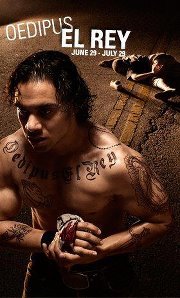

GREEK TRAGEDY IN THE ‘HOOD

Luis Alfaro’s slant on the Oedipus myth is at no point more transparent than the opening of his play, when several Latinos in orange jumpsuits sit behind bars, nodding their heads as James and Bobby Purify’s lyrics blare from a prisoner’s boombox: “I’ll do funny things if you want me to, I’m your puppet.” The men gather together in ritual to tell the story of Oedipus El Rey, a story of a man with no real choices, no escape from his fate—a life destined to tragedy before he even gets to live it. In Alfaro’s play, these men retell (and relive) the Greek myth as a ritual, commenting on the racialized, oppressive nature of prison-industrial complex and the horrors of gang violence. Victory Garden Theater’s production of Oedipus El Ray brings this passionate story of the Chicano in America to heartbreaking, hopeless realization.

Oedipus El Rey is a retelling of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, the story of a king who is bound by destiny to kill his father and wed his mother. It is the very act of seeking to avoid that fate that causes him to fulfill it. In Alfaro’s Latino interpretation, Oedipus becomes ‘king’ of an LA gang that lives by the laws of old gods and healers. It is a fascinating combination of mythology and urban street life, offering compelling insight into the Greek tragedy and into gang culture. Alfaro’s telling is somewhat forced—it’s not a likely combination, nor an easy one—but once we suspend our disbelief, it is an exceptionally rewarding interpretation.

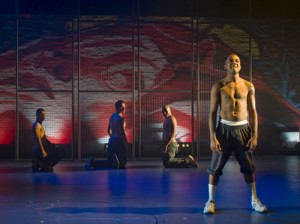

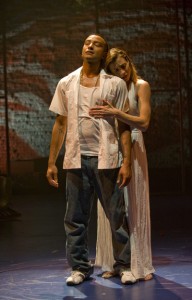

The beating heart of this production is director Chay Yew, who makes immediately clear that he won’t allow the audience to watch the story unfold from a safe distance, sending the prisoners out into the audience to begin their ritual. We are never permitted the detachment we might feel during a traditional telling of Oedipus Rex, as the men are emphatic that, “this is our story!” Yew’s pacing makes it feel that way throughout the entire 95 minutes—this drama moves quickly, and is constantly engaging without ever feeling rushed. While Yew’s fast-paced storytelling is impressive, his best work is in his still, more intimate scenes. The moment when Oedipus and his mother Jocasta go to bed together, having pillow-talk while nude downstage on a rotating platform, is sensual and serene, but wrought with premonitory undertones of the tragic horror that lies ahead. Kevin Depinet’s set, a series of jailhouse iron bars and graffiti covered buildings, is beautifully utilized throughout.

The beating heart of this production is director Chay Yew, who makes immediately clear that he won’t allow the audience to watch the story unfold from a safe distance, sending the prisoners out into the audience to begin their ritual. We are never permitted the detachment we might feel during a traditional telling of Oedipus Rex, as the men are emphatic that, “this is our story!” Yew’s pacing makes it feel that way throughout the entire 95 minutes—this drama moves quickly, and is constantly engaging without ever feeling rushed. While Yew’s fast-paced storytelling is impressive, his best work is in his still, more intimate scenes. The moment when Oedipus and his mother Jocasta go to bed together, having pillow-talk while nude downstage on a rotating platform, is sensual and serene, but wrought with premonitory undertones of the tragic horror that lies ahead. Kevin Depinet’s set, a series of jailhouse iron bars and graffiti covered buildings, is beautifully utilized throughout.

Yew only steps astray in the scene where Oedipus confronts the healers/sphinx to become king; the scene didn’t feel in tune with the rest of the piece. The hissing of the healers as they became the sphinx felt almost comical, as the three men whirled around stage with blankets over their head. The scene isn’t helped by Ryan Bourque’s fight choreography, which feels cheap and clumsy. This unwieldy scene certainly poses a problem in staging to begin with, but it’s one that Yew doesn’t quite overcome.

Yew only steps astray in the scene where Oedipus confronts the healers/sphinx to become king; the scene didn’t feel in tune with the rest of the piece. The hissing of the healers as they became the sphinx felt almost comical, as the three men whirled around stage with blankets over their head. The scene isn’t helped by Ryan Bourque’s fight choreography, which feels cheap and clumsy. This unwieldy scene certainly poses a problem in staging to begin with, but it’s one that Yew doesn’t quite overcome.

Adam Poss’ Oedipus is cool, confident, and handsome. He plays the role with a certain naïve arrogance that works well with this role; under Poss’ care, Oedipus is definitely compelling but not particularly complex. Charin Alvarez, on the other hand, brings depth to Jocasta that can’t quite be matched by the rest of the cast. There is a certain sadness and strength to Alvarez’ performance that makes her not only the star of this cast, but also the tragic core of this production.

Arturo Soria (Creon) and ensemble members Jesse David Perez and Steve Casillas are also remarkably strong. The two exceptions are Madrid St. Angelo as Lauis and Eddie Torres as Tiresius. St. Angelo doesn’t quite channel enough machismo to make him believable as Oedipus’s tyrannical father—he doesn’t feel like a king, a murderer, or even really a misogynist; it is a capable performance, but lacks dimension. Torres’ Tiresius, the blind prophet who raises Oedipus after his father attempts to kill him, stumbles around stage and voices inspirational quotes, but he doesn’t bring anything interesting or charismatic to the role—a role which, at least in Oedipus Rex, I find the most fascinating. Neither of these two are particularly believable as inmates at the beginning either, and are a liability throughout.

Even with these issues, Alfaro effectively adapts Sophocles’ tragedy to take on entirely new implications, making it a powerful statement against prison infrastructure and the treatment of race in America. Ultimately, it seems Oedipus and his fellow inmates are no more than puppets, manipulated by a system of strings that sets them up for the same tragic end over and over again. Alfaro’s play shines a light on those strings, but what’s most devastating here is the utter hopelessness of the situation. Just as within the story, it feels as though the more we struggle and try to break these strings, the more entangled we become.

photos by Michael Brosilow

Oedipus El Rey

Victory Gardens Biograph Theater, 2433 N. Lincoln Ave

Tues-Fri at 7:30; Sat at 3 & 7:30; Sun at 3

ends on July 29, 2012

for tickets, call 773.871.3000 or visit Victory Gardens

for more shows, visit Theatre in Chicago