THERE’S NOT AN APP FOR THAT

Enough already. First, I applaud The Dallas Opera for taking a chance on Tod Machover’s new experimental opera Death and the Powers, as well as the diligent cast and crew. I also commend Los Angeles’ cool new opera company, The Industry, for presenting the “world’s first live interactive opera,” and the beneficent Hammer Museum for hosting the free occasion. But for all the hoopla about multimedia “this” and sci-fi opera “that,” the live simulcast of this excruciating ninety-minute opera was a hokey pretentious mess. Any philanthropic critical assessments—“maybe it was better in the theater,” “a prodigious cast,” “the libretto had its moments”—are mere buoys in the tidal wave of mediocrity on display at the Billy Wilder Theater (the opera was beamed from Dallas to nine theaters worldwide).

Enough already. First, I applaud The Dallas Opera for taking a chance on Tod Machover’s new experimental opera Death and the Powers, as well as the diligent cast and crew. I also commend Los Angeles’ cool new opera company, The Industry, for presenting the “world’s first live interactive opera,” and the beneficent Hammer Museum for hosting the free occasion. But for all the hoopla about multimedia “this” and sci-fi opera “that,” the live simulcast of this excruciating ninety-minute opera was a hokey pretentious mess. Any philanthropic critical assessments—“maybe it was better in the theater,” “a prodigious cast,” “the libretto had its moments”—are mere buoys in the tidal wave of mediocrity on display at the Billy Wilder Theater (the opera was beamed from Dallas to nine theaters worldwide).

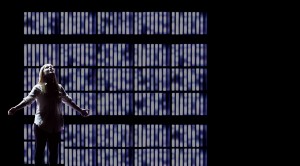

Some of the disappointment arrives courtesy of the presenter’s insistence on the event’s import, but the live digital technology was just as feeble as the opera it was intended to enhance. Audience members were instructed to download the “Powers Live” app to offer an “omniscient view of the action of the opera” and to “access the inner world of the main character, Simon Powers”…”who transfers his consciousness to an omniscient robot ‘system’ in order to perpetuate his existence beyond the decay of his physical being.” But no app in the world can save this opera, which was originally directed by Diane Paulus for American Repertory Theater in 2011. Alex McDowell’s production design contains impressive technological achievements, such as Bob Hsiung and Michael Miller’s remote-controlled robots, but the thing would have done better at a science fair.

Some of the disappointment arrives courtesy of the presenter’s insistence on the event’s import, but the live digital technology was just as feeble as the opera it was intended to enhance. Audience members were instructed to download the “Powers Live” app to offer an “omniscient view of the action of the opera” and to “access the inner world of the main character, Simon Powers”…”who transfers his consciousness to an omniscient robot ‘system’ in order to perpetuate his existence beyond the decay of his physical being.” But no app in the world can save this opera, which was originally directed by Diane Paulus for American Repertory Theater in 2011. Alex McDowell’s production design contains impressive technological achievements, such as Bob Hsiung and Michael Miller’s remote-controlled robots, but the thing would have done better at a science fair.

Imagine if an anarchist and a futurist half-baked a sci-fi musical, wrote some glorified Seussian quasi-poetry, and hired some sixty year-old synth geek to punch-up a John Adams tune, and you have an idea of what Death feels like. The score could have been serviceable had Machover deleted the constant tinkling MIDI triteness, which bumped the score from potential drama into 70’s sci-fi weirdness. Poet-laureate Robert Pinsky’s libretto (from a story by Pinsky and Randy Weiner) poses provocative questions, such as “what happens to humans when consciousness can exist eternally in technology?” In fact, the story is the greatest asset, and the libretto has potential. But Machover completely abuses the message, repeating Pinsky’s already verbose prose to a pulp, and fastening the text willy-nilly to oblique and anti-dramatic vocal lines. Just as disturbing to my ears was the news that Machover was nominated as a finalist for the 2012 Pulitzer Award in music.

Imagine if an anarchist and a futurist half-baked a sci-fi musical, wrote some glorified Seussian quasi-poetry, and hired some sixty year-old synth geek to punch-up a John Adams tune, and you have an idea of what Death feels like. The score could have been serviceable had Machover deleted the constant tinkling MIDI triteness, which bumped the score from potential drama into 70’s sci-fi weirdness. Poet-laureate Robert Pinsky’s libretto (from a story by Pinsky and Randy Weiner) poses provocative questions, such as “what happens to humans when consciousness can exist eternally in technology?” In fact, the story is the greatest asset, and the libretto has potential. But Machover completely abuses the message, repeating Pinsky’s already verbose prose to a pulp, and fastening the text willy-nilly to oblique and anti-dramatic vocal lines. Just as disturbing to my ears was the news that Machover was nominated as a finalist for the 2012 Pulitzer Award in music.

Contributing to the screening’s failure was a horrible mix mostly reliant on contact mics. Part of the reason opera is presented in big theaters is to demonstrate its grandness. Opera singers love to project. If you tape microphones to their face and shove cameras up their noses, you lose the essential feature of their years of training and reduce the acoustic of a big theater to that of a broom cupboard. Being below the stage, instrumentalists already struggle to project; the mix clipped the orchestra’s wings too.

Contributing to the screening’s failure was a horrible mix mostly reliant on contact mics. Part of the reason opera is presented in big theaters is to demonstrate its grandness. Opera singers love to project. If you tape microphones to their face and shove cameras up their noses, you lose the essential feature of their years of training and reduce the acoustic of a big theater to that of a broom cupboard. Being below the stage, instrumentalists already struggle to project; the mix clipped the orchestra’s wings too.

Prior to this insufferable event, made worse by an overall air of preciousness, we were presented with pre-show material consisting of almost an hour of advertisements, along with commentary from a host of the contributors: the charming and eloquent lead Robert Orth; the conductor Nicole Paiement (it’s refreshing to see a female maestro); and the composer himself, who tellingly hesitated before saying, “We hope you get it.”

But the cherry on top was the proprietary, opera-enhancing app, the use of which was either fruitless or downright hilarious. Ultimately this game-breaker–only available to those with newer operating systems on their smartphones and tablets–was just a silly diversion. My favorite part: When the instruction “shake” appeared on the devices (which were distractingly lit up the entire show), the only thing it prompted was audience members simulating epileptic fits and masturbation. The sole contribution from their expensive apparatuses, aside from putting money into the pockets of The Powers, was a blank screen interspersed with goofy light shows and images of what already appeared on stage in Dallas.

But the cherry on top was the proprietary, opera-enhancing app, the use of which was either fruitless or downright hilarious. Ultimately this game-breaker–only available to those with newer operating systems on their smartphones and tablets–was just a silly diversion. My favorite part: When the instruction “shake” appeared on the devices (which were distractingly lit up the entire show), the only thing it prompted was audience members simulating epileptic fits and masturbation. The sole contribution from their expensive apparatuses, aside from putting money into the pockets of The Powers, was a blank screen interspersed with goofy light shows and images of what already appeared on stage in Dallas.

There is a fitting and ironic undertone here: While the opera itself and the app-centric event extoll the virtues of embracing technology, the dorkiness of the app accentuated the piece’s failure. The creators are going for an epic comment on humans and our relationship to digital consciousness, but they created an opera and an event which inadvertently comments on how technology is getting in the way of true art.

photos by Jonathan Williams, Carter Rose, Jill Steinberg, and Paula Aguilera

Death and the Powers

The Dallas Opera at Winspear Opera House

presented by The Industry

screened at the Hammer Museum in Westwood

played on February 16, 2014

click here for future Hammer events

click here for more info on The Industry

click here for more info on The Dallas Opera

click here for more info on Death and the Powers