INTRIGUE? I’M GLAD YOU MASKED

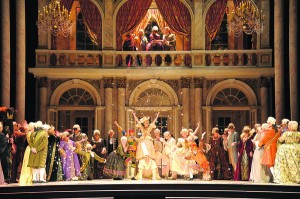

The poster of San Diego Opera’s production of Verdi’s A Masked Ball claims “Based on a True Story.” This is not hyperbole. When their production opens on Saturday with a not-to-be-missed cast, the opulent setting you will see is the court of King Gustav III in 18th-century Sweden. This is indeed the location of an actual event which inspired the opera: King Gustav’s assassination.

Yet when Un ballo in maschera opened in Rome on Feb. 17, 1859, Verdi and his librettist Antonio Somma had written the opera as such, but transferred the action from Europe to British colonial Boston, replacing Gustav III with a character  named Riccardo, the Count (or Earl) of Warwick. It wasn’t until the last six decades of the twentieth century that most productions restored the original Swedish setting and characters’ names. What happened?

named Riccardo, the Count (or Earl) of Warwick. It wasn’t until the last six decades of the twentieth century that most productions restored the original Swedish setting and characters’ names. What happened?

First, the story of Verdi’s opera actually begins with another opera: Gustave III, ou Le bal masque (“Gustavus III, or The Masked Ball”) by French composer Daniel François Esprit Auber. Eugène Scribe’s libretto for this 1833 grand opera in five acts (a.k.a. an opéra historique) did not contain a historically accurate narrative, but it nonetheless concerned the same true story.

King Gustav III, who assumed power after a coup d’état in 1772, was determined to restore royal autocracy. During the French Revolution (1789-1799), Gustav established an allegiance to Louis XVI, going so far as to offer Swedish assistance to help reinstate him after the Storming of the Bastille in 1789. While Gustav belonged  to a growing cadre of leaders who embraced Enlightenment, he was nonetheless an absolute monarch, and would fall victim to a widespread collusion among his aristocratic enemies. You know, it always gets a little sticky when one emphasizes reason and individualism rather than tradition, but does so from an ivory tower.

to a growing cadre of leaders who embraced Enlightenment, he was nonetheless an absolute monarch, and would fall victim to a widespread collusion among his aristocratic enemies. You know, it always gets a little sticky when one emphasizes reason and individualism rather than tradition, but does so from an ivory tower.

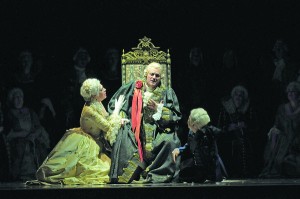

On March 16, 1792, an anonymous letter written in French threatening Gustav’s life was delivered to the king while he dined with friends prior to a masked ball at Stockholm’s Royal Opera House, which Gustav himself founded. Ah, so many missives, so many threats. He snubbed the letter, and soon upon entering the masquerade ball, he was encircled by Swedish military officer Jacob Johan Anckarström and his co-conspirators Counts Horn and Ribbing. The pistol-shot that Anckarström fired into Gustav’s back did not immediately kill the king, who would die 13 days later from an infected wound, but it certainly fueled Les Misérables to continue their class war.

All of the aforementioned characters are in Verdi’s opera, along with Madame Arvidson, based on the real life fortune teller Ulrica Arfvidsson, who consulted Gustav when he met with her in disguise in 1786. Among other predictions, including regicide, she warned, “Beware of the man with a sword you will meet this evening, for he aspires to take your life.” Turns out that Gustav bumped into a guy with a sword leaving his sister-in-law’s apartment later that day, and it was none other than Count Horn (naturally, Arfvidsson was well-known for having a web of moles who aided in her “predictions,” and she was said to be very helpful when interrogated about the king’s murder).

All of the aforementioned characters are in Verdi’s opera, along with Madame Arvidson, based on the real life fortune teller Ulrica Arfvidsson, who consulted Gustav when he met with her in disguise in 1786. Among other predictions, including regicide, she warned, “Beware of the man with a sword you will meet this evening, for he aspires to take your life.” Turns out that Gustav bumped into a guy with a sword leaving his sister-in-law’s apartment later that day, and it was none other than Count Horn (naturally, Arfvidsson was well-known for having a web of moles who aided in her “predictions,” and she was said to be very helpful when interrogated about the king’s murder).

As if this cast of characters isn’t ripe enough for an opera, Scribe (a great name for a librettist!) added to Auber’s opera another character: Amélie, who would become in Verdi’s opera Amelia, Anckarström’s wife who just happens to be having an unconsummated love affair with the king. (It seems that despotism wasn’t enough incentive for regicide.) As Dumas wrote in his play, The Mohicans of Paris, “Cherchez la femme,” or when a man behaves out of character, the cause is always a woman.

As if this cast of characters isn’t ripe enough for an opera, Scribe (a great name for a librettist!) added to Auber’s opera another character: Amélie, who would become in Verdi’s opera Amelia, Anckarström’s wife who just happens to be having an unconsummated love affair with the king. (It seems that despotism wasn’t enough incentive for regicide.) As Dumas wrote in his play, The Mohicans of Paris, “Cherchez la femme,” or when a man behaves out of character, the cause is always a woman.

Just as fascinating as the story of Gustav III of Sweden is that of Verdi and the censors. There is a reason why Verdi and Somma changed the character of Gustavo, King of Sweden to Riccardo, Governor of Boston: The Hays Code of 1850s’ Italy. Authorities had little problem with forbidden desire and gory murder in the opera; they were worried that the portrayal of duplicity and regicide in a European court’”even in far-off Sweden’”might set the stage for the plebeians to rehearse the uprising (indeed, on Jan. 14, 1858, three Italians had attempted to assassinate Emperor Napolean III in Paris). From Naples to Rome, nasty lawsuits and more censorship ensued, and Verdi simply was done changing the opera anymore. Instead of altering their opus, which up to this time was titled Una vendetta in dominò, the writers simply changed the names, and moved the story to Massachusetts, a location which was paradoxically on everyone’s mind during the French Revolution (remember that the treaty which ended the American Revolutionary War in 1783 was signed in Paris).

Just as fascinating as the story of Gustav III of Sweden is that of Verdi and the censors. There is a reason why Verdi and Somma changed the character of Gustavo, King of Sweden to Riccardo, Governor of Boston: The Hays Code of 1850s’ Italy. Authorities had little problem with forbidden desire and gory murder in the opera; they were worried that the portrayal of duplicity and regicide in a European court’”even in far-off Sweden’”might set the stage for the plebeians to rehearse the uprising (indeed, on Jan. 14, 1858, three Italians had attempted to assassinate Emperor Napolean III in Paris). From Naples to Rome, nasty lawsuits and more censorship ensued, and Verdi simply was done changing the opera anymore. Instead of altering their opus, which up to this time was titled Una vendetta in dominò, the writers simply changed the names, and moved the story to Massachusetts, a location which was paradoxically on everyone’s mind during the French Revolution (remember that the treaty which ended the American Revolutionary War in 1783 was signed in Paris).

So, 155 years later, the setting and characters’ names are back in their rightful place. Justice has come full circle and now we can get back to murder and adultery, along with prophesizing, political machinations, and an awesome royal costume party all set to Verdi’s magnificent score. Add to that Bulgarian soprano Krassimira Stoyanova, American mezzo Stephanie Blythe, and the incredibly in-demand Polish lyric tenor Piotr Beczala’”all outfitted in John Conklin’s zestfully detailed costumes’”and this event becomes one ball to die for.

So, 155 years later, the setting and characters’ names are back in their rightful place. Justice has come full circle and now we can get back to murder and adultery, along with prophesizing, political machinations, and an awesome royal costume party all set to Verdi’s magnificent score. Add to that Bulgarian soprano Krassimira Stoyanova, American mezzo Stephanie Blythe, and the incredibly in-demand Polish lyric tenor Piotr Beczala’”all outfitted in John Conklin’s zestfully detailed costumes’”and this event becomes one ball to die for.

photos of Lyric Opera of Chicago’s production by Dan Rest

A Masked Ball

A Masked Ball

San Diego Opera

San Diego Civic Theatre

1100 3rd Ave

(Corner of Third Ave and B Street)

Saturday March 8, 2014 at 7 pm

Tuesday March 11, 2014 at 7 pm

Friday, March 14, 2014 at7 pm

Sunday, March 16, 2014 at 2 pm

for tickets, call (619) 533-7000

or visit www.SDopera.com

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

It is definitely a cast to die for.

It puzzles me why the Domingo-led LA Opera which is a much bigger (and supposedly more influential) than the San Diego Opera keeps casting mostly B grade/C grade singers in their operas, while San Diego Opera mostly casts A/A-minus grade talent in their operas. In San Diego, leads usually have major role credits from the Met, Royal Opera, and the Vienna State Opera. In LA, leads seem to have their credits from Tulsa, Kansas City, and Zagreb.