DRUID’S EVER STURDY CRIPPLE

Since I think that the Druid and Atlantic Theater Company production of Martin McDonagh’s The Cripple of Inishmaan, under the sublime direction of Garry Hynes, is as close to perfection as we can reasonably expect the theater to get, I am offering  up my review of their original production [both linked here and reprinted below]. Dearbhla Molloy and Laurence Kinlan are the only actors left from that cast, but it makes little difference, since the new ensemble enters the world of the play with such raw feeling, such comic precision, such fervor, and such a profound understanding of the poignancy that lies just beneath the surface sourness, that it is every bit as rich an experience as it was when I first saw it. It is too bad that Angelenos are deprived of the opportunity to see the great Marie Mullen, but Ingrid Craigie, who has inherited her part, captures the play’s quirky rhythms with funny and touching results. This is a masterpiece of comic writing, made haunting by Ms. Hynes’s perceptive understanding of what is sneakily hiding between the lines. Anyone in love with the theater would be crazy to miss The Cripple of Inishmaan.

up my review of their original production [both linked here and reprinted below]. Dearbhla Molloy and Laurence Kinlan are the only actors left from that cast, but it makes little difference, since the new ensemble enters the world of the play with such raw feeling, such comic precision, such fervor, and such a profound understanding of the poignancy that lies just beneath the surface sourness, that it is every bit as rich an experience as it was when I first saw it. It is too bad that Angelenos are deprived of the opportunity to see the great Marie Mullen, but Ingrid Craigie, who has inherited her part, captures the play’s quirky rhythms with funny and touching results. This is a masterpiece of comic writing, made haunting by Ms. Hynes’s perceptive understanding of what is sneakily hiding between the lines. Anyone in love with the theater would be crazy to miss The Cripple of Inishmaan.

The Cripple of Inishmaan

Druid Theatre Company

Center Theatre Group

Kirk Douglas Theatre in Culver City

scheduled to end on May 1, 2011

for tickets, visit http://www.centertheatregroup.org/

—————————-

MARTIN McDONAGH’S FEVER DREAM OF A PLAY

originally published January 9, 2009

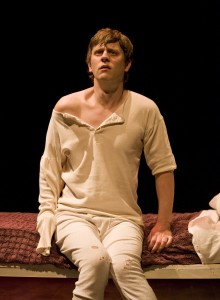

[Editor’s note: the photos used in this review are from the current cast]

Oh, they exist all right, those fabled Aran Islands, with their rugged terrains surrounded by what, in rough weather, can be a terrifying Galway Bay, but Inishmaan and Inishmore, as real as they are, exist as much in the fever brain of Martin McDonagh, who has placed them on a map, along with Inisheer, Leenane and Connemara, outside of Ireland: the map of contemporary theater. And even though McDonagh was born in England (just as John Ford – whose Inishfree’s rolling green meadows are forever a part of The Quiet Man rather than a part any true Irish landscape – was born in Maine), the Ireland he has created for the stage is as authentic as it is dedicated to the mythologies the great Irish dramatists have always been bent on creating. Do we take him as seriously as we do John Millington Synge? Or do we see him as an outsider hurling invective at the shenanigans of those “stage Irish?” Is he having fun with the land of the leprechauns, where ghosts walk hand in hand with the living inhabitants, or is he looking bitterly and sadly at their peculiar and peculiarly fascinating ways?

Oh, they exist all right, those fabled Aran Islands, with their rugged terrains surrounded by what, in rough weather, can be a terrifying Galway Bay, but Inishmaan and Inishmore, as real as they are, exist as much in the fever brain of Martin McDonagh, who has placed them on a map, along with Inisheer, Leenane and Connemara, outside of Ireland: the map of contemporary theater. And even though McDonagh was born in England (just as John Ford – whose Inishfree’s rolling green meadows are forever a part of The Quiet Man rather than a part any true Irish landscape – was born in Maine), the Ireland he has created for the stage is as authentic as it is dedicated to the mythologies the great Irish dramatists have always been bent on creating. Do we take him as seriously as we do John Millington Synge? Or do we see him as an outsider hurling invective at the shenanigans of those “stage Irish?” Is he having fun with the land of the leprechauns, where ghosts walk hand in hand with the living inhabitants, or is he looking bitterly and sadly at their peculiar and peculiarly fascinating ways?

When The Cripple of Inishmaan first made its way to New York in an often misguided and somewhat troublesome production a decade ago at the Public Theater, it seemed, even then, to be a wonderful piece of blarney. But it has taken Garry Hynes, the great director of the Druid Theatre Company, in its current incarnation at the Atlantic Theater Company, to bring the play to artistic fruition, to release its mockery and its daffiness and, at the same time, to reveal its haunted heart. There is no funnier or more heartbreaking play in town at the moment. Ms. Hynes knows her Irish theater and she knows exactly what McDonagh is laughing at, and she also knows that McDonagh knows that what cannot be taken away from the Irish is their brooding sense of the tragic.

When The Cripple of Inishmaan first made its way to New York in an often misguided and somewhat troublesome production a decade ago at the Public Theater, it seemed, even then, to be a wonderful piece of blarney. But it has taken Garry Hynes, the great director of the Druid Theatre Company, in its current incarnation at the Atlantic Theater Company, to bring the play to artistic fruition, to release its mockery and its daffiness and, at the same time, to reveal its haunted heart. There is no funnier or more heartbreaking play in town at the moment. Ms. Hynes knows her Irish theater and she knows exactly what McDonagh is laughing at, and she also knows that McDonagh knows that what cannot be taken away from the Irish is their brooding sense of the tragic.

The play takes place in 1934 on the island of Inishmaan, and its conceit is that its villagers are in pursuit of taking part in the filming of Robert Flaherty’s classic Man of Aran, whose crews are shooting at a neighboring island. They pooh-pooh the idea of Cripple Billy – whose tortured body will surely remind older theatergoers of the way in which John Merrick’s body was twisted out of shape by Philip Anglim in the original production of The Elephant Man – going with them. But, of course, it is Cripple Billy who gets sent off to Hollywood, complete with contract. And, of course again, at just the time when a screening of the finished Man of Aran is shown at the local church, Cripple Billy is possibly dying in a Hollywood hotel, a rotting piece of human decay in the center of the hotel’s flashing lights. But The Cripple of Inishmaan has its happy ending. Or does it? At least, Cripple Billy returns to Inishmaan.

The play takes place in 1934 on the island of Inishmaan, and its conceit is that its villagers are in pursuit of taking part in the filming of Robert Flaherty’s classic Man of Aran, whose crews are shooting at a neighboring island. They pooh-pooh the idea of Cripple Billy – whose tortured body will surely remind older theatergoers of the way in which John Merrick’s body was twisted out of shape by Philip Anglim in the original production of The Elephant Man – going with them. But, of course, it is Cripple Billy who gets sent off to Hollywood, complete with contract. And, of course again, at just the time when a screening of the finished Man of Aran is shown at the local church, Cripple Billy is possibly dying in a Hollywood hotel, a rotting piece of human decay in the center of the hotel’s flashing lights. But The Cripple of Inishmaan has its happy ending. Or does it? At least, Cripple Billy returns to Inishmaan.

He returns to the original stew of thwarted lives and inherent violence that he left behind. There’s Kate and Eileen, who have raised Cripple Billy (after the mysterious death of his parents), running the grocery whose entire stock seems to be made up of tinned peas and fresh eggs, most of which are more likely to be broken on the head of Bartley by his sister, the slut, Helen, than eaten by anybody in town. There’s Johnny PateenMike, who sells gossip in trade for anything he can get, and who is anxiously anticipating the imminent death of his bedridden mother, Mammy, whose advanced state of alcoholism would have killed anyone else ages ago, and who, incidentally, drinks because she instinctively knows her son is trying to kill her. And there’s Babby Bobby, the man who brings Cripple Billy to the filming when nobody else will take him, and who hides, beneath his gentle exterior, a storehouse of violent subterranean emotions. A lively cast of characters, indeed, to be stranded on an island with, particularly when it’s BabbyBobby who’s got the only lifeboat!

He returns to the original stew of thwarted lives and inherent violence that he left behind. There’s Kate and Eileen, who have raised Cripple Billy (after the mysterious death of his parents), running the grocery whose entire stock seems to be made up of tinned peas and fresh eggs, most of which are more likely to be broken on the head of Bartley by his sister, the slut, Helen, than eaten by anybody in town. There’s Johnny PateenMike, who sells gossip in trade for anything he can get, and who is anxiously anticipating the imminent death of his bedridden mother, Mammy, whose advanced state of alcoholism would have killed anyone else ages ago, and who, incidentally, drinks because she instinctively knows her son is trying to kill her. And there’s Babby Bobby, the man who brings Cripple Billy to the filming when nobody else will take him, and who hides, beneath his gentle exterior, a storehouse of violent subterranean emotions. A lively cast of characters, indeed, to be stranded on an island with, particularly when it’s BabbyBobby who’s got the only lifeboat!

The marvelous cast Ms. Hynes has assembled create an ensemble that should be envied by every other theater company around (and this in a season of memorable ensemble performances). What makes each characterization so vibrant is how fully their innate absurdity is projected while the pitiable aspects of their humanity keep peering through. I mention them all here: Dearbhla Molloy’s open-faced Eileen, forever hiding her favorite candies and forever searching for them; David Pearse’s worm-eaten Johnny PateenMike, who can’t make a move that doesn’t bring suspicion upon him but who, in fact, simply can’t make a move; Laurence Kinlan’s amiable, slightly brutish buffoon of a Bartley; Kerry Condon’s saucily indelicate Helen; Andrew Connolly’s hearty, handsome and profoundly secretive Babby Bobby; Patricia O’Connell’s dry Mammy, happily guzzling her gin while life cheerily passes her by; John C. Vennema’s doctor, the play’s voice of reason (which may be one of the reasons why we remember least of all what it is he says); Aaron Monaghan’s Cripple Billy, an astonishing portrait of coughing human anguish and

The marvelous cast Ms. Hynes has assembled create an ensemble that should be envied by every other theater company around (and this in a season of memorable ensemble performances). What makes each characterization so vibrant is how fully their innate absurdity is projected while the pitiable aspects of their humanity keep peering through. I mention them all here: Dearbhla Molloy’s open-faced Eileen, forever hiding her favorite candies and forever searching for them; David Pearse’s worm-eaten Johnny PateenMike, who can’t make a move that doesn’t bring suspicion upon him but who, in fact, simply can’t make a move; Laurence Kinlan’s amiable, slightly brutish buffoon of a Bartley; Kerry Condon’s saucily indelicate Helen; Andrew Connolly’s hearty, handsome and profoundly secretive Babby Bobby; Patricia O’Connell’s dry Mammy, happily guzzling her gin while life cheerily passes her by; John C. Vennema’s doctor, the play’s voice of reason (which may be one of the reasons why we remember least of all what it is he says); Aaron Monaghan’s Cripple Billy, an astonishing portrait of coughing human anguish and  wary hopefulness inside a tormented physicality that captures incisively the dueling nature of McDonagh’s play. As for Marie Mullen as Kate, Eileen’s crabbed but sensible sister, I have come to the conclusion, after seeing her in The Beauty Queen of Leenane and in the rich variety of characters she played in Druid/Synge and now, in her impeccable playing of this character, that she is one of the world’s greatest living actresses. To be in the potent presence of her company is reason enough to drop everything and run off to see The Cripple of Inishmaan.

wary hopefulness inside a tormented physicality that captures incisively the dueling nature of McDonagh’s play. As for Marie Mullen as Kate, Eileen’s crabbed but sensible sister, I have come to the conclusion, after seeing her in The Beauty Queen of Leenane and in the rich variety of characters she played in Druid/Synge and now, in her impeccable playing of this character, that she is one of the world’s greatest living actresses. To be in the potent presence of her company is reason enough to drop everything and run off to see The Cripple of Inishmaan.

It is clear that even if Martin McDonagh is having mercilessly mean fun with the Irish character and with the deliciously poetic idiosyncrasies of Irish language, he also has a sweeping compassion for the Irish soul, and Garry Hynes, his perfect collaborator, understands, with a Beckettian sense of truth, that the vaudeville house stands right next door to the cemetery.

To see this re-printed review as it was originally published, visit http://old.stageandcinema.com/crippleofinishmaan.html

published January 9, 2009Oh, they exist all right, those fabled Aran Islands, with their rugged terrains surrounded by what, in rough weather, can be a terrifying Galway Bay, but Inishmaan and Inishmore, as real as they are, exist as much in the fever brain of Martin McDonagh, who has placed them on a map, along with Inisheer, Leenane and Connemara, outside of Ireland: the map of contemporary theater. And even though McDonagh was born in England (just as John Ford – whose Inishfree’s rolling green meadows are forever a part of The Quiet Man rather than a part any true Irish landscape – was born in Maine), the Ireland he has created for the stage is as authentic as it is dedicated to the mythologies the great Irish dramatists have always been bent on creating. Do we take him as seriously as we do John Millington Synge? Or do we see him as an outsider hurling invective at the shenanigans of those “stage Irish?” Is he having fun with the land of the leprechauns, where ghosts walk hand in hand with the living inhabitants, or is he looking bitterly and sadly at their peculiar and peculiarly fascinating ways?When The Cripple of Inishmaan first made its way to New York in an often misguided and somewhat troublesome production a decade ago at the Public Theater, it seemed, even then, to be a wonderful piece of blarney. But it has taken Garry Hynes, the great director of the Druid Theatre Company, in its current incarnation at the Atlantic Theater Company, to bring the play to artistic fruition, to release its mockery and its daffiness and, at the same time, to reveal its haunted heart. There is no funnier or more heartbreaking play in town at the moment. Ms. Hynes knows her Irish theater and she knows exactly what McDonagh is laughing at, and she also knows that McDonagh knows that what cannot be taken away from the Irish is their brooding sense of the tragic.The play takes place in 1934 on the island of Inishmaan, and its conceit is that its villagers are in pursuit of taking part in the filming of Robert Flaherty’s classic Man of Aran, whose crews are shooting at a neighboring island. They pooh-pooh the idea of Cripple Billy – whose tortured body will surely remind older theatergoers of the way in which John Merrick’s body was twisted out of shape by Philip Anglim in the original production of The Elephant Man – going with them. But, of course, it is Cripple Billy who gets sent off to Hollywood, complete with contract. And, of course again, at just the time when a screening of the finished Man of Aran is shown at the local church, Cripple Billy is possibly dying in a Hollywood hotel, a rotting piece of human decay in the center of the hotel’s flashing lights. But The Cripple of Inishmaan has its happy ending. Or does it? At least, Cripple Billy returns to Inishmaan.

He returns to the original stew of thwarted lives and inherent violence that he left behind. There’s Kate and Eileen, who have raised Cripple Billy (after the mysterious death of his parents), running the grocery whose entire stock seems to be made up of tinned peas and fresh eggs, most of which are more likely to be broken on the head of Bartley by his sister, the slut, Helen, than eaten by anybody in town. There’s Johnny PateenMike, who sells gossip in trade for anything he can get, and who is anxiously anticipating the imminent death of his bedridden mother, Mammy, whose advanced state of alcoholism would have killed anyone else ages ago, and who, incidentally, drinks because she instinctively knows her son is trying to kill her. And there’s Babby Bobby, the man who brings Cripple Billy to the filming when nobody else will take him, and who hides, beneath his gentle exterior, a storehouse of violent subterranean emotions. A lively cast of characters, indeed, to be stranded on an island with, particularly when it’s BabbyBobby who’s got the only lifeboat!

The marvelous cast Ms. Hynes has assembled create an ensemble that should be envied by every other theater company around (and this in a season of memorable ensemble performances). What makes each characterization so vibrant is how fully their innate absurdity is projected while the pitiable aspects of their humanity keep peering through. I mention them all here: Dearbhla Molloy’s open-faced Eileen, forever hiding her favorite candies and forever searching for them; David Pearse’s worm-eaten Johnny PateenMike, who can’t make a move that doesn’t bring suspicion upon him but who, in fact, simply can’t make a move; Laurence Kinlan’s amiable, slightly brutish buffoon of a Bartley; Kerry Condon’s saucily indelicate Helen; Andrew Connolly’s hearty, handsome and profoundly secretive Babby Bobby; Patricia O’Connell’s dry Mammy, happily guzzling her gin while life cheerily passes her by; John C. Vennema’s doctor, the play’s voice of reason (which may be one of the reasons why we remember least of all what it is he says); Aaron Monaghan’s Cripple Billy, an astonishing portrait of coughing human anguish and wary hopefulness inside a tormented physicality that captures incisively the dueling nature of McDonagh’s play. As for Marie Mullen as Kate, Eileen’s crabbed but sensible sister, I have come to the conclusion, after seeing her in The Beauty Queen of Leenane and in the rich variety of characters she played in Druid/Synge and now, in her impeccable playing of this character, that she is one of the world’s greatest living actresses. To be in the potent presence of her company is reason enough to drop everything and run off to see The Cripple of Inishmaan.

It is clear that even if Martin McDonagh is having mercilessly mean fun with the Irish character and with the deliciously poetic idiosyncrasies of Irish language, he also has a sweeping compassion for the Irish soul, and Garry Hynes, his perfect collaborator, understands, with a Beckettian sense of truth, that the vaudeville house stands right next door to the cemetery.