A TENNESSEE WILLIAMS CARICATURE

A number of theatres in Los Angeles have marked the 100th anniversary of Tennessee Williams’ birth by staging productions of his plays. Following upon the successful runs of A House Not Meant To Stand at The Fountain Theatre and Five Beauties at the McCadden Theatre is the Elephant Theatre Company’s production of Baby Doll at the Lillian. Unlike those productions, this one is not based on a fully-fledged piece of Williams’ dramatic writing. Rather, it is based on the 1956 film Baby Doll, directed by Elia Kazan. Although Baby Doll is based on Williams’ one-act play “27 Wagons Full of Cotton,” Kazan claims in his autobiography to have written the majority of the screenplay. The latter claim seems plausible when this play is compared to Williams’ others, for Baby Doll is not so well-written, lacking the dramatic force, religious mania, and well-crafted dialogue of his best plays. In short, Baby Doll is a caricature of a Tennessee Williams play.

Despite the lackluster quality of the script, the Elephant Theatre Company fails to lift Baby Doll above the morass. Unevenness characterizes the production and is its chief fault. For the first thirty minutes, the audience has little idea of what is going on because the plot is so poorly introduced. When one enters the theater, cast members are simply lying about on set, as if asleep. As the performance begins, they begin to wake and move bales of cotton and pieces of furniture, clearing the set of its original clutter. But they move as if in a trance, guided by an over-stylized choreography that ill-fits a Tennessee Williams play. It is only much later that one makes the connection between these bales of cotton and one of the principal events in the plot: Archie Lee Meighan’s burning down of his competitor Silva Vacarro’s cotton gin in order to gain a monopoly on cotton production.

Despite the lackluster quality of the script, the Elephant Theatre Company fails to lift Baby Doll above the morass. Unevenness characterizes the production and is its chief fault. For the first thirty minutes, the audience has little idea of what is going on because the plot is so poorly introduced. When one enters the theater, cast members are simply lying about on set, as if asleep. As the performance begins, they begin to wake and move bales of cotton and pieces of furniture, clearing the set of its original clutter. But they move as if in a trance, guided by an over-stylized choreography that ill-fits a Tennessee Williams play. It is only much later that one makes the connection between these bales of cotton and one of the principal events in the plot: Archie Lee Meighan’s burning down of his competitor Silva Vacarro’s cotton gin in order to gain a monopoly on cotton production.

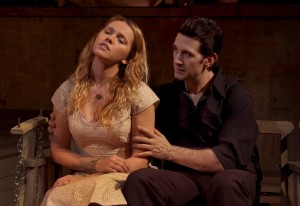

Another oddity of the production is the singing of two folk songs not more than five minutes apart. These disturb the flow of the action and seem a kind of aesthetic distraction. The songs, sung by Chloe Petersen and Bernadette Speakes, are pleasant in and of themselves, but if they are meant to add local color to the set, then they have surely failed. These songs are more reminiscent of the bluegrass of Kentucky or Tennessee than the blues and spirituals of the play’s Mississippi setting. If these early aspects of the production – the singing and choreography – were followed through in the remainder of the play, one might be able to view them more benignly. Instead, they are an anomaly. Each of the three principal characters – Silva Vacarro (Ronnie Marmo), Baby Doll Meighan (Lulu Brud) and Archie Lee Meighan (Tony Gatto) – further adds to the unevenness of the play by his/her dialogue. It’s difficult to tell that Silva’s character is Sicilian until he tells us so, because Marmo’s Sicilian accent is slow to warm up and develop a rhythm. And the same goes for the Meighans’ southern accents. Baby Doll doesn’t really begin to run smoothly until halfway through the performance.

Another oddity of the production is the singing of two folk songs not more than five minutes apart. These disturb the flow of the action and seem a kind of aesthetic distraction. The songs, sung by Chloe Petersen and Bernadette Speakes, are pleasant in and of themselves, but if they are meant to add local color to the set, then they have surely failed. These songs are more reminiscent of the bluegrass of Kentucky or Tennessee than the blues and spirituals of the play’s Mississippi setting. If these early aspects of the production – the singing and choreography – were followed through in the remainder of the play, one might be able to view them more benignly. Instead, they are an anomaly. Each of the three principal characters – Silva Vacarro (Ronnie Marmo), Baby Doll Meighan (Lulu Brud) and Archie Lee Meighan (Tony Gatto) – further adds to the unevenness of the play by his/her dialogue. It’s difficult to tell that Silva’s character is Sicilian until he tells us so, because Marmo’s Sicilian accent is slow to warm up and develop a rhythm. And the same goes for the Meighans’ southern accents. Baby Doll doesn’t really begin to run smoothly until halfway through the performance.

Baby Doll is not the most enjoyable of theatergoing experiences, and this is more by reason of its content than any qualitative deficiencies in the current production. Archie Lee Meighan and Silva Vacarro are both mean, disreputable men. Archie manhandles his wife in such an abusive way that it almost makes you sick to your stomach. It’s no wonder that Baby Doll withholds her body from her all-too-willing husband. Silva has the potential to be Baby Doll’s knight in shining armor, but instead he squanders the opportunity by taking his revenge on Archie (for burning down his cotton gin). And Silva takes his revenge in the form of Baby Doll’s virginity, which she gives up only too willingly in the naïve hope that Silva will take her away from Archie.

If Tony Gatto’s performance as Archie is good in that it makes us despise his character, Lulu Brud’s performance is lacking by comparison. Whereas we should naturally feel sympathy for one in her situation, she fails to evoke it. She doesn’t even exude the sex appeal that got the original film banned in many countries. It’s as if she doesn’t know the measure of her own sexual magnetism. The most noteworthy performance is actually that of Jacque Lynn Colton, who plays the minor part of Aunt Rose. Her character is comically eccentric, yet played with just the right amount of pathos. Having seen this production, it is easy to imagine “27 Wagons Full of Cotton” as a powerfully dramatic and ambitious one-act play. It’s adaptation into Baby Doll, whether the fault of Elia Kazan or not, draws the blood out and leaves it lifeless. What’s left is but a pale shadow, neither worthy of the Elephant Theatre Company or Tennessee Williams.

If Tony Gatto’s performance as Archie is good in that it makes us despise his character, Lulu Brud’s performance is lacking by comparison. Whereas we should naturally feel sympathy for one in her situation, she fails to evoke it. She doesn’t even exude the sex appeal that got the original film banned in many countries. It’s as if she doesn’t know the measure of her own sexual magnetism. The most noteworthy performance is actually that of Jacque Lynn Colton, who plays the minor part of Aunt Rose. Her character is comically eccentric, yet played with just the right amount of pathos. Having seen this production, it is easy to imagine “27 Wagons Full of Cotton” as a powerfully dramatic and ambitious one-act play. It’s adaptation into Baby Doll, whether the fault of Elia Kazan or not, draws the blood out and leaves it lifeless. What’s left is but a pale shadow, neither worthy of the Elephant Theatre Company or Tennessee Williams.

photos by Joel Daavid

Baby Doll

Lillian Theatre in Los Angeles

scheduled to end on January 8, 2012

EXTENDED TO JANUARY 22, 2012

for tickets, visit http://www.babydollatthelillian.com