THE QUESTION IS: CAN YOU SEE TOMMY?

Everything is murky about the DOMA Theatre Company’s new production of The Who’s Tommy at the Met Theatre’”the performances, the sound design, the staging, the choreography, and especially the lighting. Often actors are hardly visible when they sing, and the lighting design seemingly hasn’t been created with any thought to focusing the audience’s attention. That is a huge problem for a production that has trouble delineating what is happening on stage, why it is happening, what it means, and what we should be watching at any given moment.

Tommy is a bit of a mess on a lot of levels, starting with the material itself. Of the different versions’”the original 1969 rock opera by The Who, the 1975 Ken Russell film, and the 1993 Broadway stage show, the stage show is the least narratively coherent’”both in terms of the story itself, and the emotional transitions that take us from one moment to another.

Tommy is a bit of a mess on a lot of levels, starting with the material itself. Of the different versions’”the original 1969 rock opera by The Who, the 1975 Ken Russell film, and the 1993 Broadway stage show, the stage show is the least narratively coherent’”both in terms of the story itself, and the emotional transitions that take us from one moment to another.

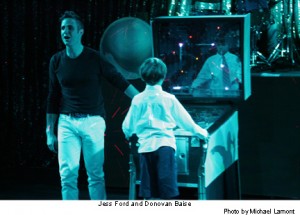

A man goes off to war and is thought killed in action. His son Tommy is born and his widow takes up with another man. When the husband turns up very much alive he catches his wife and her lover in flagrante and kills the lover. Little Tommy witnesses it, and is brainwashed into believing he didn’t see it, hear it, and can’t say anything to anyone about it, which triggers some sort of psychotic break, and he goes deaf, dumb, and blind. In a journey that involves child abuse, molestation, a trip to an acid dealer, and a lot of other unpleasantness, Tommy grows up, finds improbable success playing pinball’”though he still cannot see or hear’”and, finally, regains his senses through staring into a broken mirror, becomes a sort of cult leader, and in the end, his adoring followers turn on him’”possibly killing him, possibly just hurting his feelings’”before the whole troupe troops into the audience and forces everyone to clap in rhythm to “Listening to You.”

A man goes off to war and is thought killed in action. His son Tommy is born and his widow takes up with another man. When the husband turns up very much alive he catches his wife and her lover in flagrante and kills the lover. Little Tommy witnesses it, and is brainwashed into believing he didn’t see it, hear it, and can’t say anything to anyone about it, which triggers some sort of psychotic break, and he goes deaf, dumb, and blind. In a journey that involves child abuse, molestation, a trip to an acid dealer, and a lot of other unpleasantness, Tommy grows up, finds improbable success playing pinball’”though he still cannot see or hear’”and, finally, regains his senses through staring into a broken mirror, becomes a sort of cult leader, and in the end, his adoring followers turn on him’”possibly killing him, possibly just hurting his feelings’”before the whole troupe troops into the audience and forces everyone to clap in rhythm to “Listening to You.”

I saw the original stage production on Broadway, but had largely forgotten many of its flaws. The film, which I saw as a young kid, had stayed in my memory, supplanting whatever memories I had of the stage version’”mainly because of its amazing performances: Ann-Marget was Oscar-nominated for her wonderfully demented, over-the-top turn as the mother, Elton John played the Pinball Wizard and made the song a hit all over again, Tina Turner was electric as the Acid Queen, and Jack Nicholson, Roger Daltry, Oliver Reed, and Keith Moon skillfully rounded out the cast.

I saw the original stage production on Broadway, but had largely forgotten many of its flaws. The film, which I saw as a young kid, had stayed in my memory, supplanting whatever memories I had of the stage version’”mainly because of its amazing performances: Ann-Marget was Oscar-nominated for her wonderfully demented, over-the-top turn as the mother, Elton John played the Pinball Wizard and made the song a hit all over again, Tina Turner was electric as the Acid Queen, and Jack Nicholson, Roger Daltry, Oliver Reed, and Keith Moon skillfully rounded out the cast.

Therein lies the problem both with this production and with the conception of the stage musical itself: It has no stars. By “stars” I don’t mean famous people’”I mean people who can rivet your attention by sheer force of will. In structuring the stage musical it was as if Des McAnuff, who worked with The Who’s Pete Townshend to reshape the material, wanted the show itself to be the star rather than individual performers. While I fundamentally disagree with that decision, the Broadway show certainly backed it up with the saving grace of innovative staging and choreography. It became a huge hit and ran for two years.

The production at the Met has no such saving grace.

The cavernous stage is poorly utilized, with a two dimensional approach to blocking, no appreciable attempt at a workable set design, the afore-mentioned lack of a coherent lighting design, and pedestrian, haphazard choreography. Director Hallie Baran doesn’t seem to have a clue. She sends her actors out an ugly mélange of unflattering costumes and cheap wigs, and gives them movement that points up their limitations rather than highlights whatever strengths they may possess.

The mission of Dolf Ramos and Marco Gomez, the “Do” and “Ma” of the DOMA Theatre Company, is to bring together seasoned professionals and up and coming talent to nurture the next generation of artists, but if there are no true professionals on hand to provide such seasoning, the effort seems misdirected or even pointless. A great deal of time, energy, and passion motivates the company, and their ambition is high: The rest of the season includes Once on this Island, Xanadu, and Jekyll & Hyde. Are we meant to applaud the attempt itself? Our culture’s psychological and human development strategy has become one of rewarding effort rather than achievement. I’m not a fan of the idea. Nor do I want to sit idly by and let it take the theater hostage.

The mission of Dolf Ramos and Marco Gomez, the “Do” and “Ma” of the DOMA Theatre Company, is to bring together seasoned professionals and up and coming talent to nurture the next generation of artists, but if there are no true professionals on hand to provide such seasoning, the effort seems misdirected or even pointless. A great deal of time, energy, and passion motivates the company, and their ambition is high: The rest of the season includes Once on this Island, Xanadu, and Jekyll & Hyde. Are we meant to applaud the attempt itself? Our culture’s psychological and human development strategy has become one of rewarding effort rather than achievement. I’m not a fan of the idea. Nor do I want to sit idly by and let it take the theater hostage.

photos by Michael Lamont

The Who’s Tommy

DOMA Theatre Company at the Met in Hollywood (Los Angeles Theater)

through April 15

for tickets, visit http://www.domatheatre.com