TIMON ON OUR HANDS

OK, raise your hand if you have read Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens. No? Do you even know how to say Timon? It is pronounced TIME-uhn. Have you seen a production? Probably not, as it is rarely produced. Well, guess what? It most likely wasn’t even produced in Shakespeare’s time. The scholarly guess is that the “tragedy†was written around 1606, but no production records exist prior to its 1623 Folio publication. Yet even after 1623, this five-act play is easily the least-produced work out of Shakespeare’s canon. The rendition currently on at Chicago Shakespeare Theater (CST) proves why this estimable company is one of the finest regional theaters in the country, but this version also elucidates why the play is rarely staged. It appears in Act One that Artistic Director Barbara Gaines was poised to prove any Timon naysayers wrong with a briskly-paced, rousingly inventive, accessible adaptation, but Act Two sadly confirms that this play may just be unsavable.

As of the 21st Century, the accepted theory is that Shakespeare had a co-author named Thomas Middleton, but regardless of how the play came into being, it is nonetheless a most problematic piece, basically because the main character is given little to no background that would validate his quick descent from a happy-go-lucky philanthropic businessman to a hapless, hopeless misanthrope. Plus, there’s a huge cast of supporting players, from senators to servants, who are difficult to tell apart based on their characteristics; an inconsequential love story (cut from the production at Chicago Shakespeare); and unexplained plot developments.

As of the 21st Century, the accepted theory is that Shakespeare had a co-author named Thomas Middleton, but regardless of how the play came into being, it is nonetheless a most problematic piece, basically because the main character is given little to no background that would validate his quick descent from a happy-go-lucky philanthropic businessman to a hapless, hopeless misanthrope. Plus, there’s a huge cast of supporting players, from senators to servants, who are difficult to tell apart based on their characteristics; an inconsequential love story (cut from the production at Chicago Shakespeare); and unexplained plot developments.

At CST, the first act is easily one of the most enthralling, ravishing and fascinating Shakespearean theatrical experiences in memory. Gaines’ streamlined adaptation combines characters into one, and cuts out extraneous storylines, even as she still uses an enormous (and superlative) cast. The design elements are breathtaking, even as the Wall Street milieu is quickly becoming clichéd in Shakespeare productions of the last few years. Kevin Depinet’s set design is reminiscent of a chrome-covered board room, with giant TV screens hurling down from above, and Robert Wierzel’s circular pools of light are inspired. Mike Tutaj designed the projections,  Susan E. Mickey the costumes, and Lindsay Jones is responsible for the sound and original music.

At CST, the first act is easily one of the most enthralling, ravishing and fascinating Shakespearean theatrical experiences in memory. Gaines’ streamlined adaptation combines characters into one, and cuts out extraneous storylines, even as she still uses an enormous (and superlative) cast. The design elements are breathtaking, even as the Wall Street milieu is quickly becoming clichéd in Shakespeare productions of the last few years. Kevin Depinet’s set design is reminiscent of a chrome-covered board room, with giant TV screens hurling down from above, and Robert Wierzel’s circular pools of light are inspired. Mike Tutaj designed the projections,  Susan E. Mickey the costumes, and Lindsay Jones is responsible for the sound and original music.

Timon, (gloriously interpreted by Ian McDiarmid), a rich and generous futures-trading tycoon, throws a lavish banquet for his bevy of friends; among them are artists, senators, military personnel and bankers. The only dissenter among them is Apemantus (James Newcomb), a philosopher who balks at these so-called friends, perceiving them as flattering takers; he won’t even have anything to do with the sexy dancers that Timon hired for his grand fete.

Timon, (gloriously interpreted by Ian McDiarmid), a rich and generous futures-trading tycoon, throws a lavish banquet for his bevy of friends; among them are artists, senators, military personnel and bankers. The only dissenter among them is Apemantus (James Newcomb), a philosopher who balks at these so-called friends, perceiving them as flattering takers; he won’t even have anything to do with the sexy dancers that Timon hired for his grand fete.

No doubt Timon is reckless with his money: he buys a gaudy ring from a Jeweller (William Dick); strains his charity by supporting a freeloading Writer (Kevin Gudahl) and Artist (Timothy Edward Kane); and pays off the debts of another dubious friend, Ventidius (Terry Hamilton). As with most bankers throughout history, however, Timon’s money doesn’t really belong to him, so when creditors come calling, he ignores the advice of his true friend and steward Flauvius (Sean Fortunato), and seeks financial assistance all over Athens. In a clever sequence where Timon’s associates are working out at a gym or being tailored, Flauvius is roundly denied.  Timon receives the news by incongruously flying into an overwrought rage (why does he not confront the friends himself?) Instead, Timon throws another banquet, but serves stones with hot water as supper, generally railing against the unkindness of humanity.

No doubt Timon is reckless with his money: he buys a gaudy ring from a Jeweller (William Dick); strains his charity by supporting a freeloading Writer (Kevin Gudahl) and Artist (Timothy Edward Kane); and pays off the debts of another dubious friend, Ventidius (Terry Hamilton). As with most bankers throughout history, however, Timon’s money doesn’t really belong to him, so when creditors come calling, he ignores the advice of his true friend and steward Flauvius (Sean Fortunato), and seeks financial assistance all over Athens. In a clever sequence where Timon’s associates are working out at a gym or being tailored, Flauvius is roundly denied.  Timon receives the news by incongruously flying into an overwrought rage (why does he not confront the friends himself?) Instead, Timon throws another banquet, but serves stones with hot water as supper, generally railing against the unkindness of humanity.

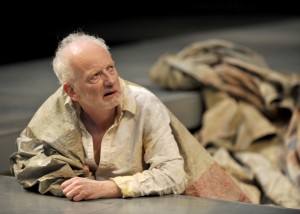

In the second act, Timon has become a hermit on the beach (another technical triumph of design), but only two things happen in this tedious portion of the show: first, Timon, after some more general railing, discovers Fort Knox-like gold bullion bars buried in the sand, which delighted the audience to no end. Even though we have no idea where this gold came from, we suspect that Timon will now exact revenge or somehow have his comeuppance. Not even close. Instead, old “friends†who hear of Timon’s brand-new wealth, unsurprisingly appear to share the treasure. But the entire second act is a showcase for Mr. McDiarmid, who rages, rants, and rails (and then rages, rants and rails some more) against the hatefulness of man. He starves himself to death just after bequeathing the gold to Flauvius, who becomes the new financial bigwig in Athens. Now tell me, is that any way to treat a friend?

In the second act, Timon has become a hermit on the beach (another technical triumph of design), but only two things happen in this tedious portion of the show: first, Timon, after some more general railing, discovers Fort Knox-like gold bullion bars buried in the sand, which delighted the audience to no end. Even though we have no idea where this gold came from, we suspect that Timon will now exact revenge or somehow have his comeuppance. Not even close. Instead, old “friends†who hear of Timon’s brand-new wealth, unsurprisingly appear to share the treasure. But the entire second act is a showcase for Mr. McDiarmid, who rages, rants, and rails (and then rages, rants and rails some more) against the hatefulness of man. He starves himself to death just after bequeathing the gold to Flauvius, who becomes the new financial bigwig in Athens. Now tell me, is that any way to treat a friend?

It is guaranteed that you will not leave the theater complaining of boredom, and CST is to be commended for proving how unworkable this play is, but there may be a lesson in all of this: maybe theaters around the country will stop over-producing playwrights’ unworthy works because of their popular name (LaBute and Mamet come to mind) if we can be politically incorrect enough to admit even the Bard himself created a stinker – whether he had help or not.

It is guaranteed that you will not leave the theater complaining of boredom, and CST is to be commended for proving how unworkable this play is, but there may be a lesson in all of this: maybe theaters around the country will stop over-producing playwrights’ unworthy works because of their popular name (LaBute and Mamet come to mind) if we can be politically incorrect enough to admit even the Bard himself created a stinker – whether he had help or not.

photos by Liz Lauren

Timon of Athens

Chicago Shakespeare Theater on Navy Pier in Chicago

through June 10

for tickets, call 312.595.5600 or visit http://www.chicagoshakes.com