PICKING THROUGH AMBIGUITIES

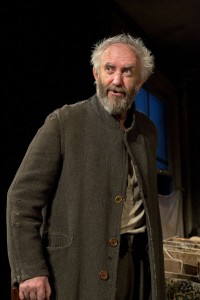

In Harold Pinter’s purposefully ambiguous The Caretaker (1960), currently playing at Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Harvey Theater, Davies (Jonathan Pryce) is a transient who is invited by Aston (Alan Cox) to stay in a dilapidated London house. All the action takes place in one crummy, cluttered room that is also frequented by Aston’s eccentric and threatening brother Mick (Alex Hassell). Though full of bravado, Davies is well aware of his place on the second-lowest rung of society; it even takes him some minutes to accept Aston’s invitation just to sit down in a chair. Before long, Davies makes himself at home, becoming more and more demanding as the play progresses, and turning positively tyrannical soon after both Aston and Mick independently offer him the position of caretaker at the house.

Mr. Pryce is brilliant in his portrayal of the resourceful and cunning Davies, a boastful derelict who is full of false hopes and delusions of grandeur; he’s a liar who doesn’t know if he’s lying to or about himself, bitter yet hopeful, weak yet predatory. Mr. Price’s performance captures these nuances with elegant precision. He paints a truthful and vivid picture of Davies’ life, which is so essential to playing a Pinterian role like this one, where we don’t ever find out the real facts of the character’s existence.

Mr. Pryce is brilliant in his portrayal of the resourceful and cunning Davies, a boastful derelict who is full of false hopes and delusions of grandeur; he’s a liar who doesn’t know if he’s lying to or about himself, bitter yet hopeful, weak yet predatory. Mr. Price’s performance captures these nuances with elegant precision. He paints a truthful and vivid picture of Davies’ life, which is so essential to playing a Pinterian role like this one, where we don’t ever find out the real facts of the character’s existence.

Pryce’s performance, along with a rich technical design, should have had the makings of compelling theater, yet the show was ultimately tiresome, due to both the cloudy performances of Mr. Cox and Mr. Hassell, and the uncertain vision of director Christopher Morahan. The characters of Aston and Mick are like icebergs, in that the playwright tells us precious little about the brothers. The unseen mass – that is, Pinter’s intentionally vague actualities of character – forces an actor to create meaning behind the text. Unfortunately, both Mr. Cox and Mr. Hassell failed in this regard, undermining the entire production; their seeming lack of both choices and character motivation made Pinter’s indistinct meanings come off as awkward and sloppy. It is unclear is if this was due to the skilled and talented actors or the interpretation of director Christopher Morahan.

Aston has a well-known monologue regarding his past experiences with electro-shock therapy, used to treat hallucinations. In a BBC program, Colin Firth performed the monologue as a man destroyed, but who at one time had spirit, strength, ambition, imagination, and a rich (maybe too rich) mental life. There was a real sense of a young man, a boy really, who possessed all those things, who was alive and free, but who one day had his strength, his hope, and his mind ripped out from him, creating a shadow of his former self, a leftover thing that hasn’t yet died. This is Aston’s tragedy, and inside this tragedy is the drama.

Mr. Cox’s Aston, on the other hand, is simply helpless to the point of pathetic, a choice which is neither compelling nor dramatic. We are never made to feel, on a visceral level, that at one time he might have been someone different. There’s a point at which he describes a struggle where he’d “laid out” a hospital orderly, but looking at Mr. Cox’s Aston one could say almost certainly that there was never an incarnation of him that was capable, physically or emotionally, of laying out anyone. Is the director implying that Aston is still hallucinating?

As Mick, Mr. Hassell suffers from a similar problem, in that we don’t get the a sense of his life outside of his relatively brief appearances on the stage. Mick is the first character we see in the play, standing alone in the room, his back to the audience. He stands still for a while, then turns his head. After hearing footsteps, he runs out and hides in the hallway. We do not know who he is, why he is there, or what happened before, so Hassell must somehow fill in the blanks in order to command our attention from the start. Did he come there from work, a rape, a card game, or a trip to the zoo? Is he hungover? Does he have hemorrhoids? Is he hungry or horny or lonely? Elsewhere in the play, one has the sense that the actor (not the character) is confused, or at least unsure of what’s going on. The motivations behind Mr. Hassell’s performance seem to be jumbled together, as opposed to being specific from line to line, word to word and moment to moment.

In most plays we see the action as if through a window. In The Caretaker we look through a keyhole. This makes it all the more vital that everything outside our field of vision be precise and correct. If not, then we do not trust the things that we see. This play offers a great many ambiguities and unanswered questions: Why does Aston invite a disgusting, smelly old bum to his room? And is it in fact his house or his brother’s? Why is Mick hanging around in the first place? Why is he trying to both frighten and befriend Davies? Why is it that the brothers hardly talk to each other and never have a scene together? Is Mick brain-damaged like Aston? Is he even real or is he in fact someone’s hallucination? And if so, whose?

The answers to some of these questions may be easier to find than others. For example, clues in the dialogue suggest that both Aston and Mick are attracted to Davies as a sort of father figure (albeit a comical one), to serve as their caretaker, as a poor old man for them to take care of, and finally as a parent to reject. But questions behind the scenario seem neither to be asked nor answered by Cox, Hassell and Morahan.

The set, designed by Eileen Diss, is rich enough in detail and texture to comfortably entertain over two hours of scrutiny. Add to that the spot-on lighting by Colin Grenfell, Dany Everett’s serviceable costumes, and Tom Lishman’s crisp sound design, and the result is a living space that is at once real and theatrical.

The set, designed by Eileen Diss, is rich enough in detail and texture to comfortably entertain over two hours of scrutiny. Add to that the spot-on lighting by Colin Grenfell, Dany Everett’s serviceable costumes, and Tom Lishman’s crisp sound design, and the result is a living space that is at once real and theatrical.

There is good confusion and bad confusion in the theater. Good confusion is when you think things are happening according to a certain set of laws but then discover that something completely different is in fact happening. Bad confusion is when false clues are unintentionally created by imprecision, and where laws can be broken as needed. Ambiguity and absurdity only work, are only meaningful, truthful, and artistic if everything around them is precise. Otherwise, things turn murky, and coherence is lost. Hence, watching The Caretaker was like trying to pick out lost peanut halves from a bowl full of shells.

photos by Richard Termine

The Caretaker

Theater Royal Bath Productions/Liverpool Everyman

Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Harvey Theater

651 Fulton St. in Brooklyn

ends on June 17, 2012

for tickets, call 718-636-4100 or visit BAM

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

I must contest your assessment. The show’s characters may be confused, but the show is hardly confusing. It may revel in ambiguity, but only the productive kind.

Read the extent of my disagreement on my own blog. Here’s an excerpt:

“There should be a special circle of hell devoted to theatregoers who are unwilling to wait five minutes after a performance has ended to give the actors their due, because they must be the first ones to the taxis and their cars, as if the actors were trained monkeys who existed only from curtain to curtain for their wearied amusement. This kind of oafish behavior is especially galling after a performance as fine as the one I saw Thursday night at BAM in the Theatre Royal Bath’s production of Harold Pinter’s The Cartetaker, which aside from the persons of great distinction heading to their vehicles to clog the atmosphere, received a well-deserved standing ovation from the rest of us.”