DEAFTRAP

Writer Stephen Sachs and the Fountain Theatre have come up with what would appear to be a fresh approach to Rostand’s classic play, Cyrano de Bergerac. In this modern-day version, Cyrano is no longer the joyful poet, soldier, and owner of a humongous proboscis, but a frustrated poet who happens to be deaf. He falls for the poetry-loving Roxy, who is hearing, but she’s hot for his brother Chris, a hard-rocking, alcoholic musician who reciprocates Roxy’s affections. Chris is based on Christian, the gorgeous, elegant soldier who adores Roxanne, but lacks aesthetics; Rostand’s Christian states, “I must find some way of meeting her. I am dying of love!†Sachs’ Chris states, “She’s, like, a freak. Insane. Gets my bone hard. Big time.†Yuck.

Cyrano, ashamed to pursue Roxy because of his deafness, decides to express his love for her through Chris’s text-messages, even as Cyrano despises social media. Roxy sleeps with the drug-consuming, dim-witted loser Chris, which naturally upsets Cyrano even more. After Chris departs for a tour with his band, a series of events leads to Cyrano’s new-found pride in his deafness. The dialogue is told in a variety of formats, from American Sign Language (ASL) to video monitor displays. A fresh approach which sounds inspiring, right?

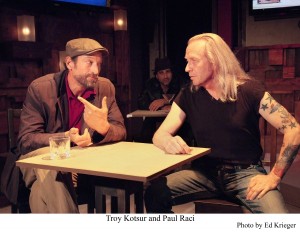

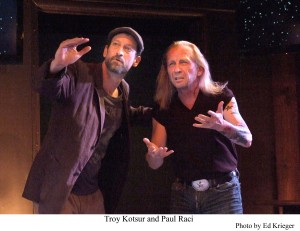

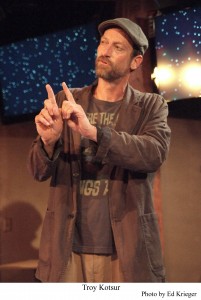

Yes, it’s a great idea and a commendable attempt, with a stunning and marvelous central performance by deaf actor Troy Kotsur. There are indeed some lovely moments of humor and pathos, with some fascinating insights into modern technology and communication, but the enterprise, as a whole, left a bad taste in my mouth.

It collapses upon itself for a number of reasons: Sachs’s writing incorporates some lovely poetic passages for Cyrano, but they appear alongside choppy, churlish dialogue; lead characters with little to no back story are hyper-self-aware and mostly unsympathetic, shallow and/or unnecessarily vulgar; and lesser characters are so underdeveloped that they don’t even have names, such as Deafie #4 and Hearing #1 (which is fine with the huge cast of almost 50 in Rostand’s version, but not on a tiny stage with 13 actors).

Sachs subtitled his play “a modern-day deaf/hearing fable.†A fable is designed to teach us a lesson, but it must be credible and grounded in truth. Cyrano never feels believable, not just due to the dialogue, but because of Simon Levy’s unfocused direction and a substandard speaking cast which recites lines haltingly, as if they were addressing children on Sesame Street – an incontrovertible irony since the character of Cyrano accuses another character of trying to speak to him as if he were a child himself.

This is a co-production with Deaf West, which, since 1990, incorporates a device in their productions that is so simple and captivatingly original that it caught the attention of the nation: when deaf actors sign their dialogue, other strategically-placed hearing actors recite the lines aloud. In A Streetcar Named Desire, the inimitable Mr. Kotsur signed Stanley’s dialogue, while a French Quarter neighbor spoke his lines from above. The effect was uncanny because the voice soon appeared to be emanating from Kotsur’s expressive hands. The brilliant gooseflesh-inducing moment occurred when Kotsur spoke out loud for the first time: “Stella-a-a-a!â€

The same applied to Deaf West’s ASL adaptations of musicals, namely Oliver! and Big River, the latter which even moved to Broadway. At one point in Big River, the entire chorus sang the same refrain over and over while signing the lyrics. Suddenly, they stopped singing, but continued signing; it was as if we could hear their voices flying from their gesticulation. It was another of my favorite theater moments of all time.

However, without great source material, Deaf West’s stunningly original concept feels particularly gimmicky, as it did with the more recent Pippin (at Mark Taper Forum) and Pinocchio (which suffered from the same identity problem as Cyrano: it smacks of Children’s Theatre with adult themes).

When it comes to assigning voices, this is one of the most confusing Deaf West productions I have seen – there were too many times in the crowd scenes that I couldn’t figure out who was speaking for whom. And while Mr. Levy could have done more to set a proper tone and clarify the proceedings, he is contending with an extremely troubling script, as evidenced in the first scene:

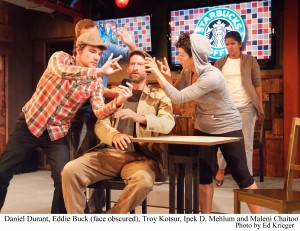

The far-fetched action begins when Cyrano rudely interrupts a conceited poet named Monty during a poetry jam in a café (paralleling the original in which Cyrano forbids the actor Montfleury to take the stage). Cyrano’s outburst (we will discover later) is motivated by his jealousy: Roxy is in the audience and the published poet Monty has eyes for her. The problem is that I felt sympathy for Monty – his poetry may have been pretentious, but it was also amusing: “I choke on stink, I breathe the rot, as putrid vapors rise, a fetid cloud burns the airways of my soul.†And although Cyrano is later chastised by both Chris and a friend named Bill for his inappropriate behavior, it’s difficult to glom onto this protagonist’s journey; Cyrano doesn’t come off as frustrated and desperate, he appears as a self-pitying, self-righteous bully.

Right away, Cyrano’s poetic dialogue feels out of context in Sachs’s contemporary re-imagining. Using brother Chris as Cyrano’s speaking voice, Sachs has the deaf poet taunt Monty with such quips as, “I may be deaf but will pummel you mute if you don’t plug your hole and its pretentious diarrhea.†To which Monty later responds, “Who the fuck do you think you are? Some deaf motherfucker telling me what poetry is? I am a published poet, god damnit! I’m not going to take this shit from you! You want to settle this? Step outside, you fucking deaf pussy! I’ll show you who the real man is!†I still shudder at the excessive and avoidable crassness in the script. Is Monty’s grossness supposed to make us appreciate Cyrano that much more? Well, it doesn’t.

And what does it matter to Monty that Cyrano is deaf? If some asshole came in and interrupted and heckled a performer, can you imagine him fleeing in sissified fear, as Monty does? Can you imagine patrons silently sitting by? Can you imagine the café owner canceling the poetry jam because of that incessantly obnoxious interferer? There was nowhere in that first long scene that I could get on board with the play.

But then Sachs’s writing shines: Instead of the 1897 Cyrano describing the many clever ways one can insult his nose, the present Cyrano lists the cunning ways to refer to his being deaf:

“Curious: ‘How do you stop a deaf argument at night, switch off the light?’

Zoological: ‘Do deaf pigs speak swine language?’

Paternal: ‘If a deaf child swears, do you wash his hands out with soap?’â€

Then, we return to the incongruities: Cyrano improvises a poem while he fistfights with a complete stranger (named Man), who is upset that the jam was cancelled. Up to now, Chris has been voicing Cyrano’s dialogue for the patrons of the bar, but how can Chris magically convert his brother’s flailing hands into perfect rhymes? And the staging of Cyrano’s somehow magical ability to fight and sign at the same time came off as awkward; it was one of the most uncomfortable stage combats I have ever witnessed, compounded by the actors in the background, whose reactions as the patrons can best be described as amateurish.

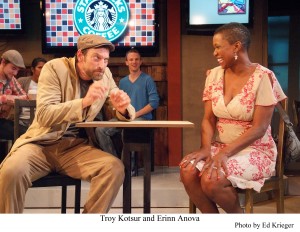

Later, at a Starbuck’s, Cyrano meets up with Roxy for the first time; naturally they have trouble communicating because she doesn’t know ASL. They whip out their phones and begin texting to each other, the missives being displayed on monitors behind them. It’s a very clever conceit, but with a major issue that slackened the pace: Roxy just discovered that Cyrano reads lips, so why does she take an interminable amount of time to text him? Why not just caption her voice on the monitor, as is done in later scenes?

Later, at a Starbuck’s, Cyrano meets up with Roxy for the first time; naturally they have trouble communicating because she doesn’t know ASL. They whip out their phones and begin texting to each other, the missives being displayed on monitors behind them. It’s a very clever conceit, but with a major issue that slackened the pace: Roxy just discovered that Cyrano reads lips, so why does she take an interminable amount of time to text him? Why not just caption her voice on the monitor, as is done in later scenes?

Then there’s the issue with so much truncated, halting dialogue. My guess is that Sachs was writing as literal interpretations of ASL. Here are some examples: Chris – “I’ve learned a lot. From you. I got this. I’ll take over from here;†Cyrano – “A trifle, a doodle. Weeks ago. Not sent.†It’s even weird when Roxie, who is practicing ASL, is given dialogue that sounds like Hollywood’s version of Native Americans: “My signing. Bad†(which would have been a funny line – were it not for the other characters who already spoke in that same pattern).

There’s more, but enough. It’s as if much of Cyrano was written with a deaf audience in mind. Even so, that doesn’t excuse the gross tactlessness in the writing, the highly unnecessary insults toward deaf people, or the gratuitous profanity.

photos by Ed Krieger

Cyrano

Fountain Theatre in Los Angeles Theater

scheduled to end on July 8 EXTENDED to July 29, 2012

for tickets, call 323.663.1525 or visit Fountain Theatre