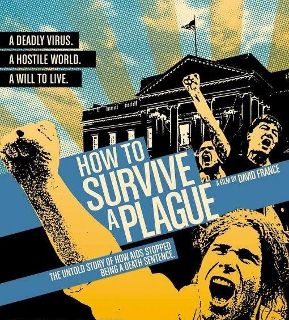

HOW TO CREATE A GREAT DOCUMENTARY

There’s a great line in the Bette Midler musical For the Boys, when, as an old woman, she is looking back on her years doing U.S.O. tours for the troops, and she quips, “Yeah, World War Two’¦ Everybody’s big break.” I thought of that when I was watching David France’s extraordinary new documentary about the early years of the AIDS crisis, How to Survive a Plague. I also thought of another wonderful war film, John Boorman’s Hope and Glory, about a boy having the best time of his life during the London Blitz.

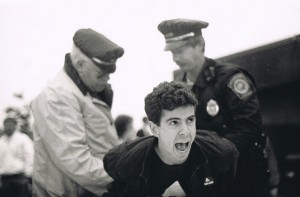

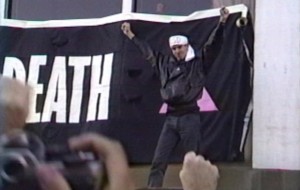

Being on the front lines of a war (or a plague) can be amazing and exciting. People find in themselves a new excellence, and a new sense of purpose that brings moments of sheer joy along with the danger and heartache. That’s one of the best things about How to Survive a Plague. As France tells the story of a group of men who helped found ACT UP in 1987, he makes us feel their exhilaration and delight in forcing the FDA, the federal government, the media, and the gay and lesbian community itself, to pay attention and do something. Their lives depend on it. And it’s downright intoxicating when they give themselves over to their justified rage; I dare you not to get giddy watching them drape a giant condom over the home of the now dead, ultra-right-wing homophobe Senator Jesse Helms.

Of course, you also feel the terror in their moments of hopelessness, and the terrible realization’”tinged with gallows humor’”that “winning” the battle over faster FDA drug approval, for some, resulted in losing the war against AIDS: Some of the drugs ACT UP compelled the FDA to distribute ended up doing more harm than good for HIV patients.

Of course, you also feel the terror in their moments of hopelessness, and the terrible realization’”tinged with gallows humor’”that “winning” the battle over faster FDA drug approval, for some, resulted in losing the war against AIDS: Some of the drugs ACT UP compelled the FDA to distribute ended up doing more harm than good for HIV patients.

That this film exists at all is something of a miracle. France sorted through over 700 hours of footage from thirty independent shooters’”some professional, many not’”and somehow he has made a cohesive whole from the different styles of videography, the varying skill levels involved, and the wildly divergent technical quality of the material. It feels like it was all created by one filmmaker, with one vision, telling one story.

France does something else remarkable: He lets the story be what it is, without proselytizing, and without succumbing to the often irresistible urge to preach to the choir. France was there during these dark days of the epidemic. You can easily imagine his own feelings and beliefs about the events that unfold here are fully formed. But he doesn’t feel and believe for you. Rather he trusts us to find the story on our own. The fact that in a clip from CNN’s Crossfire, Pat Buchanan emerges (however briefly) as a voice of reason, is not just funny and ironic’”it’s also good storytelling. You get a little jolt of surprise that reminds you to stay on your toes.

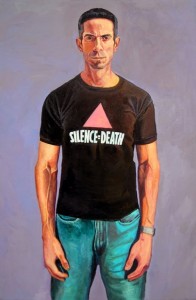

Ultimately it is a coming-of-age film. Boys become men as they face the greatest battle of their lives’”sometimes with grace; often with all-too-human moments of doubt, despair, pettiness, viciousness, even selfishness; and always with courage. The main characters make vivid transitions’”this is in many ways a kind of fractured rites-of-passage tale’”and their self-awareness is sometimes breathtaking. Particularly Peter Staley, who transforms from Wall Street bond trader to street activist to internationally respected treatment advocate; his eyes glitter with the realization of what he is doing; Can you believe this shit?’”he seems to be saying to the camera with an eager grin. Then there is the seemingly rather mousy housewife Garance Franke-Ruta, who starts asking questions from the perspective of a self-described science nerd, and ends up changing the way governments and drug companies interact. Mark Harrington and Spencer Cox are artsy and unfocused in the beginning, but become seasoned activists who grow from rabble-rousers to effective agents of real change.

It feels glib to call these people heroes. The rhetoric of heroism is often reductive in its smug certainty and situational morality. They aren’t just heroes. They’re living, breathing, human beings: complex, fascinating, contradictory, impossible, and loving. They don’t try to break your heart; they engage it fully’”which is probably a huge part of why they have accomplished so much against such incredibly high odds. They knew nothing; they felt like nobody cared; and most of them believed they were under death sentences.

They changed the world anyway.

How to Survive a Plague

Sundance Selects

USA | 2012 | 109 min. | not rated

released on September 21, 2012

to watch, visit How to Survive