THE PEASANTS ARE REVOLTING, NOT THE PRODUCTION

Set amidst the teeming, verdant jungles of South India, Encounter is an often compelling dance theatrical production from the Navarasa Dance Theater, a group that has origins in South Asia and India (though the company is currently based in Massachusetts); it is a tale of atrocity, tyranny, and caste struggle told mostly through music and the heightened realism of movement.

The drama utilizes theatrical techniques and, yes, martial arts choreography hailing from the Indian folkloric community; some may call this a dance piece, but whatever the category, it combines a timeless, mythic presentational style with a charged political message that’s strangely contemporary. The artful marriage of these theatrical forms often seems like something entirely new: Ancient dances and performance combined with modern themes and contextual backdrops. Based on East West Player’s presentation, which opened this week, dazzling staging combined with rich, sincere meaning is a potent form of political theater.

The drama utilizes theatrical techniques and, yes, martial arts choreography hailing from the Indian folkloric community; some may call this a dance piece, but whatever the category, it combines a timeless, mythic presentational style with a charged political message that’s strangely contemporary. The artful marriage of these theatrical forms often seems like something entirely new: Ancient dances and performance combined with modern themes and contextual backdrops. Based on East West Player’s presentation, which opened this week, dazzling staging combined with rich, sincere meaning is a potent form of political theater.

It is, of course, a potentially arrogant act to judge a work that finds its grounding within such an alien culture – how can we know the centuries of meaning behind a certain gesture or a particular feral howl? But to a Western viewer, half of the Navarasa Company’s charms is the way that they present their dramatic points, using methods that seem new and innovative to us, but which to a practitioner of Indian culture must seem as ancient as Kabuki theater is to a Japanese audience.

It is, of course, a potentially arrogant act to judge a work that finds its grounding within such an alien culture – how can we know the centuries of meaning behind a certain gesture or a particular feral howl? But to a Western viewer, half of the Navarasa Company’s charms is the way that they present their dramatic points, using methods that seem new and innovative to us, but which to a practitioner of Indian culture must seem as ancient as Kabuki theater is to a Japanese audience.

The play’s plot, based on Indian writer Mahasweta Devi’s short story, tells the tale of a pair of peasant field hands, beautiful Dopdi (Aparma Sindhoor) and her husband Dulna (Anil Natyaveda), who slave in the paddies all day, and then entertain their fellow workers with songs, dances, and little entertainments in the evening. An oppressed minority, the peasants live in feudal conditions, and are exploited by landowners and a vicious government that seeks to starve them off their land. Even Ganesh would turn up his trunk at their downtrodden condition – and Kali would just fling her seven arms up in sorrow.

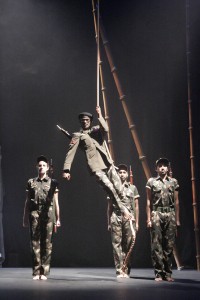

A particularly brutal general (Sunil Kumar) regards Dopdi and Dulna’s attempts to please their fellow peasants as vile rebelliousness and seeks to capture them, hoping to torture the names of other rebels in the area. When the soldiers manage to capture Dopdi, the torture she is forced to endure is depicted utilizing a stylized choreography that is both elegant and mythic, and which is somehow almost more ferociously horrifying than watching real torture. The play’s title “Encounter” refers to the military’s euphemism for “killing” the peasant rebels.

A particularly brutal general (Sunil Kumar) regards Dopdi and Dulna’s attempts to please their fellow peasants as vile rebelliousness and seeks to capture them, hoping to torture the names of other rebels in the area. When the soldiers manage to capture Dopdi, the torture she is forced to endure is depicted utilizing a stylized choreography that is both elegant and mythic, and which is somehow almost more ferociously horrifying than watching real torture. The play’s title “Encounter” refers to the military’s euphemism for “killing” the peasant rebels.

The balletic dances are interspersed with occasional English language interludes, needed to keep the sometimes benighted Western viewer in the loop with what’s going on, but the work’s overall tone strives for the mythic – the Indian mood and the modern setting often reminds one of the Peter Brooks production of Mahabarata. Indeed, the conflict itself is reduced mainly to archetypes — hard working, suffering peasants, evil soldiers – but the simplicity the basic characters provide is deceptive, belying the depth of emotion and ferocity within the choreography.

The balletic dances are interspersed with occasional English language interludes, needed to keep the sometimes benighted Western viewer in the loop with what’s going on, but the work’s overall tone strives for the mythic – the Indian mood and the modern setting often reminds one of the Peter Brooks production of Mahabarata. Indeed, the conflict itself is reduced mainly to archetypes — hard working, suffering peasants, evil soldiers – but the simplicity the basic characters provide is deceptive, belying the depth of emotion and ferocity within the choreography.

Performers Sindhoor and Natyavedi (along with co-writer S.M. Raju) adapt Devi’s story, but the intention is to use the South Indian rural setting to tell larger truths about the worldwide battle between the rich and the poor, the powerful and the powerless. The politics are, admittedly, a bit heavy handed: The lack of a particular, defined villain (or of a defined set of heroes) ultimately reduce the play’s impact; it’s a show where you feel like you’re doing good by siding with the poor people, but there’s no real definition to them or the villainous overlords. And while one doesn’t doubt that there’s much exploitation in the world, the broad strokes of the situations (the unrelentingly wicked soldiers, the angelically kind peasants) are ultimately somewhat unconvincing.

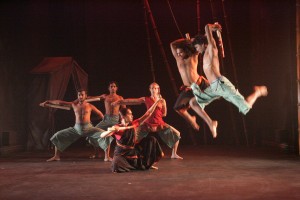

Of course, none of these political agitprop-laden intentions would matter for a damn if the show’s dancing and spectacles didn’t sustain them. And, indeed, the stage crackles with energy and adrenaline. Sindhoor and Natyaveda bring Bollywood-style experience to the politically charged routines. In one scene, a group of peasants endure a day of hideous, backbreaking labor, punctuated by loud beats and moans; in another, a battle sequence between the heroes and the villainous militia is full of both spinning, whirling jumps and swinging rifles. The indefatigable dancers who round out the cast are Raghu Narayanan, Leah Vincent, and Suvarna Raj.

Of course, none of these political agitprop-laden intentions would matter for a damn if the show’s dancing and spectacles didn’t sustain them. And, indeed, the stage crackles with energy and adrenaline. Sindhoor and Natyaveda bring Bollywood-style experience to the politically charged routines. In one scene, a group of peasants endure a day of hideous, backbreaking labor, punctuated by loud beats and moans; in another, a battle sequence between the heroes and the villainous militia is full of both spinning, whirling jumps and swinging rifles. The indefatigable dancers who round out the cast are Raghu Narayanan, Leah Vincent, and Suvarna Raj.

Sindhoor is wonderful, crackling with passion and rage as the hapless heroine, while Natyavedi’s personality is expressed as much through his gymnastics as it is through his amiable onstage character. As the diabolical general, Kumar plays his martinet character as a ruthless, business-like sadist. Production values are simple, but starkly effective. The set, credited to scenic coordinators Natyaveda, Tesshi Nakagawa, and Chris Fitch, consists of a small set of bamboo trees, a lookout pole, and a military tent; it is simple, but moodily effective. Jeremy Pivnick’s beautifully atmospheric lighting conveys the color and the tragedy of the acrobatic piece. The haunting, rythmic music is composed by Isaac Thomas Kottukapally.

Sindhoor is wonderful, crackling with passion and rage as the hapless heroine, while Natyavedi’s personality is expressed as much through his gymnastics as it is through his amiable onstage character. As the diabolical general, Kumar plays his martinet character as a ruthless, business-like sadist. Production values are simple, but starkly effective. The set, credited to scenic coordinators Natyaveda, Tesshi Nakagawa, and Chris Fitch, consists of a small set of bamboo trees, a lookout pole, and a military tent; it is simple, but moodily effective. Jeremy Pivnick’s beautifully atmospheric lighting conveys the color and the tragedy of the acrobatic piece. The haunting, rythmic music is composed by Isaac Thomas Kottukapally.

photos by Michael Lamont

Encounter

Navarasa Dance Theater Company at East West Players

Scheduled to end on October 7, 2012

for tickets call 213-625-7000 or visit http://www.eastwestplayers.org