THE HONESTY OF HYPOCRISY

The Motherfucker with the Hat by Stephen Adly Guirgis is a crackling, compelling play that finds genuine comic pathos not only in its characters’ struggles with addiction, violence, poverty, sexual compulsion, and sexual identity, but in their various, mostly unfulfilled, attempts to distinguish between the people they are and the people they pretend to be.

The abundant profanity in Hat is also filled with unexpected poetry. Every four-letter word seems at first to be little more than a casual, appropriate example of New York street vernacular’”but Guirgis is anything but casual, and his grittiness can be strangely ethereal.

The abundant profanity in Hat is also filled with unexpected poetry. Every four-letter word seems at first to be little more than a casual, appropriate example of New York street vernacular’”but Guirgis is anything but casual, and his grittiness can be strangely ethereal.

When one character, Veronica, is accused by her boyfriend Jackie of sleeping with a man who accidentally leaves his hat behind, she responds with a weird, earnest ferocity as she tries to get him to calm down:

“I didn’t fuck nobody. Jackie, you know how I am. You know I’m a little fuckin’ crazy just like you’re a little fuckin’ crazy, and you know I’d rather spit on a nun’s cunt that give a fuckin’ inch when I been wronged. I been wronged here. You wronged me. Really, really fuckin’ badly. But I will concede to you’”and it ain’t a small concession’”that I love your ass. And I’ll kick a three-legged kitten down a flight of fuckin’ stairs rather than say some shit like I love you. You know that. So let’s go get some fuckin’ pie before someone here says something that can’t be changed. Okay?”

The writing is so specific. And the flights of fancy’”spitting on a nun or kicking a three-legged kitten’”emerge not as evidence of a playwright trying to be funny, but of a character who is naturally funny.

We know she’s lying. Her boyfriend knows she’s lying. But in that moment, it’s as if she doesn’t actually know it herself. She is so lost in her own version of the truth that the strength of her passion is truer than anything as insignificant as a factual account of how she spent her day. And while not literally true, her version is actually nakedly honest.

All of the characters have similar moments of clarity and humor. They are all in, have been in, or should be in, some sort of 12-step program. Jackie is recently out of prison and must stay sober or risk violating his parole. His girlfriend Veronica, whose dialogue above is just one of her profoundly funny arias, should probably be in a program, but she is trying to get her mother’”who really has a problem’”into rehab. Ralph D. is Jackie’s sponsor, many years sober, whose grasp on the honesty inherent in the principles and practices of A.A. is illusory. Ralph’s alcoholic wife Victoria also figures in, as well as Jackie’s Cousin Julio, a seemingly gay man, married to a woman he loves, who was once in a “sex addiction fellowship.”

Guirgis successfully takes elements that shouldn’t go together and makes them work brilliantly. In Hollywood speak: Days of Wine and Roses meets Boeing-Boeing. The turgid traps of an addiction play are given an entirely different vibe by making it a kind of sex farce for the new millennium.

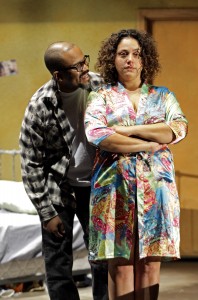

As Veronica, Elisa Bocanegra is particularly, nakedly real’”literally and figuratively. She is zaftig and far from what we might think of as the physical ideal, yet she is so proud of her sexual power, that she is sometimes as beautiful to us as she is to Jackie. Bocanegra finds moments of vulnerability that beautifully balance out the character’s ballsy, lewd bravado, finding the truth behind and inside Veronica’s raging façade.

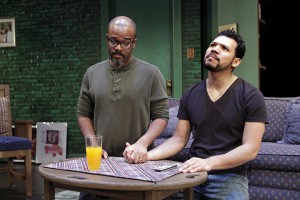

In the role that earned Bobby Cannavale a Tony on Broadway, Tony Sancho makes Jackie a wiry, twitchy, volcanic punk. When his cousin Julio confronts him with a profound truth’”that Jackie thinks of himself as a nice guy but is actually a selfish taker’”it’s a shock for Jackie, but also a relief, and Sancho makes Jackie’s slippery hold on truth, which is as slippery as his hold on sobriety, both believable and idiosyncratic.

Being Jackie’s sponsor isn’t easy for Ralph D., and the role isn’t an easy task for an actor either. Larry Bates is gifted, yet he has a harder time finding a performance balance that bridges the character’s powerful, “rigorous honesty” – in A.A. parlance – with the hypocrisy and careless brutality of his behavior. Cristina Frias is terrific as the wife who sees through Ralph’s bullshit, and through her own as well.

The most interesting character, and the most exciting performance, is Christian Barillas as Cousin Julio’”a man who never explains or apologizes for the incongruities of his life. He is an effeminate, self-described “Maricón,” unafraid of violence but unfailingly polite, kind and loyal to Jackie even as he loathes what Jackie has become, loving and jealous of his wife while cracking jokes about having gay sex. Julio celebrates and accepts life in a way that eludes the other characters, and Barillas’ simple, smart, quick approach is exactly right. He underlines absolutely nothing, and ends up getting the biggest laughs in the show.

Barillas doesn’t pause much, or turn self-contemplative; just gets on with it’”allowing Guirgis’ dialogue to blossom in its own time, while quietly finding a graceful rhythm that feels just out of reach for some of the others.

And rhythm is what’s missing from much of the production’”which plays a full twenty minutes longer than productions on Broadway and at Steppenwolf. Director Michael John Garcés lets the action get bogged down with a kind of self-reflection from the actors that is at odds with the tone of the play, and his desire to be authentic with the recovery and addiction issues gets in the way of the play’s comic engine. It isn’t about playing for laughs; it’s about trusting the playwright’s words to hit home on their own, in the hands of a quite talented cast.

The action is slowed down as if the audience needs time to allow the importance of what is happening to sink in. We don’t. We get how important what’s happening is, and we want to go for the ride. Let us. The pace is further dragged-out by the turntable set, which interrupts the flow of the piece by coming to a full stop before the next scene begins, leaving us waiting. Garcés even puts some of the actors on stage before the play begins, in dreamy contemplation, silently lurking as the audience arrives. It feels wrongheaded to me.

Some of the staging is awkward where it should be elegant and presentational where it should be tangled. And the one big fight scene is a mess. Choreographer Edgar Landa hasn’t blocked it well to begin with, and Garcés allows it to proceed with no added sound. An obviously pulled punch which looks fake to begin with is made even worse when there is no sound accompanying it.

Leah Piehl’s costumes are perfect. They make an impact when they need to, feel absolutely right for the characters, and in a show where there’s a lot of onstage dressing and undressing, they are as flexible as they need to be. The set by Nephelie Andonyadis is basically sound, but some of the props and dressing feel haphazard. They don’t detract, but they don’t add as much as they might.

Despite concerns with the production, The Motherfucker with the Hat is must-see. This is one of the best plays of the last few years and Christian Barillas’ performance is a triumph.

photos by Henry Di Rocco

The Motherfucker with the Hat

South Coast Repertory

655 Town Center Drive in Costa Mesa

ends on January 27, 2013

for tickets, call 714.708.5555 visit SCR