THE HEART OF THE MATTER

Larry Kramer’s blistering condemnation that chronicles the early years of the AIDS epidemic has arrived with an intimate production that highlights the urgency of the play but produces mixed results in casting and direction. A brilliant juxtaposition of love story and agit prop, The Normal Heart follows activist and unruly loudmouth Ned Weeks as he struggles to wake up the gay community to the presence of this strange new disease. At first glance, Tim Cummings certainly fills the shoes of Ned, a temperamental middle-aged writer who wears his Jewishness on his sleeve. Unfortunately, Cummings resorts to outlandish histrionics as character definition, with gesticulations not unlike those of Harvey Fierstein, making it awfully difficult to empathize with the character whose desperate but necessary tactics alienate those around him.

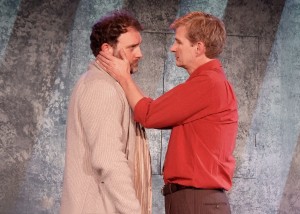

Equally difficult to buy is the relationship between Ned and his new lover, Felix, a New York Times fashion reporter. Bill Brochtrup is casting perfection as Felix, but his natural warmth and joviality is oddly put on the back burner. For some reason, he attempts to butch it up and downplay Felix’s boyishness and generous spirit. Because of the lack of chemistry between Brochtrup and Cummings, a few scenes in Act II which should be heart-wrenching and harrowing are merely uncomfortable to watch.

Equally difficult to buy is the relationship between Ned and his new lover, Felix, a New York Times fashion reporter. Bill Brochtrup is casting perfection as Felix, but his natural warmth and joviality is oddly put on the back burner. For some reason, he attempts to butch it up and downplay Felix’s boyishness and generous spirit. Because of the lack of chemistry between Brochtrup and Cummings, a few scenes in Act II which should be heart-wrenching and harrowing are merely uncomfortable to watch.

A casting coup is Fred Koehler as Mickey, a city employee who joins Ned in forming a grassroots organization needed to disseminate information. Koehler perfectly embodies this sweet man who toes the line between his desire to make a difference and, in order to keep his job, play by the rules. This inner conflict comes to a head in a powerful Act II monologue, but under Simon Levy’s direction, Koehler begins the astounding rant on such a piercingly high note that he has nowhere to go.

The best moments in this powerful and didactic but surprisingly funny play come courtesy of Matt Gottlieb as Ned’s brother, Ben, a lawyer who wants to help him in the cause, but still holds his younger sibling, whom he calls “Lemon,” as defective. Gottlieb is not just well-cast, but the consummate actor never resorts to acting trickery to develop a character. Even though Ben is a corporate player who has difficulty accepting his brother, we completely empathize with him. Also successful is Jeff Witzke in the small but mighty role of Hiram, the mayor’s aide, and Stephen O’Mahoney as Bruce, the gorgeous ex-Green Beret whose popularity, looks and non-aggressive nature make him perfect for President of this tiny and overworked organization.

The best moments in this powerful and didactic but surprisingly funny play come courtesy of Matt Gottlieb as Ned’s brother, Ben, a lawyer who wants to help him in the cause, but still holds his younger sibling, whom he calls “Lemon,” as defective. Gottlieb is not just well-cast, but the consummate actor never resorts to acting trickery to develop a character. Even though Ben is a corporate player who has difficulty accepting his brother, we completely empathize with him. Also successful is Jeff Witzke in the small but mighty role of Hiram, the mayor’s aide, and Stephen O’Mahoney as Bruce, the gorgeous ex-Green Beret whose popularity, looks and non-aggressive nature make him perfect for President of this tiny and overworked organization.

Lisa Pelikan is the churlish Dr. Brookner, who is treating more patients than anyone else in New York City. Confined to a wheelchair from polio, Brookner is not unlike Ned, and Pelikan certainly gets the frustration and hostility right, but fails utterly as she tries to imbue almost every scene with a teary emotionality. It’s as if she was forcing herself to get somewhere she thinks the character should go. She wants Brookner to be vulnerable but ends up inauthentic when she forces these inappropriate emotions. (Interestingly enough, Pelikan did not rise from her wheelchair for the curtain call, as if to say that she knows her character is so well-inhabited that it would be injurious to the audience to break the illusion.)

Lisa Pelikan is the churlish Dr. Brookner, who is treating more patients than anyone else in New York City. Confined to a wheelchair from polio, Brookner is not unlike Ned, and Pelikan certainly gets the frustration and hostility right, but fails utterly as she tries to imbue almost every scene with a teary emotionality. It’s as if she was forcing herself to get somewhere she thinks the character should go. She wants Brookner to be vulnerable but ends up inauthentic when she forces these inappropriate emotions. (Interestingly enough, Pelikan did not rise from her wheelchair for the curtain call, as if to say that she knows her character is so well-inhabited that it would be injurious to the audience to break the illusion.)

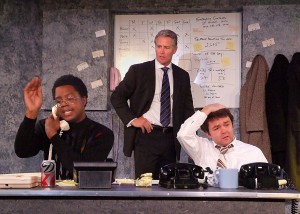

All of these actors could have been molded by Levy somehow, but it seems that the fast-paced and stunning staging consumed his attention as actors were left floundering to discover their essence. This is why some moments worked and others didn’t. Nothing could be done about the incongruous casting of Verton R. Banks as Tommy Boatwright, a self-described “Southern bitch” who knows how to handle the many personalities of this unnamed organization. Tommy goes from nerves of steel to vulnerable caretaker in a flash, but Banks’s limp and googly eyed persona just seems sorely out of place. Is it possible in a play of all white actors that this actor was cast because he is African American rather than because he is perfect for the role? (The character is not identified as black in the script.)

All of these actors could have been molded by Levy somehow, but it seems that the fast-paced and stunning staging consumed his attention as actors were left floundering to discover their essence. This is why some moments worked and others didn’t. Nothing could be done about the incongruous casting of Verton R. Banks as Tommy Boatwright, a self-described “Southern bitch” who knows how to handle the many personalities of this unnamed organization. Tommy goes from nerves of steel to vulnerable caretaker in a flash, but Banks’s limp and googly eyed persona just seems sorely out of place. Is it possible in a play of all white actors that this actor was cast because he is African American rather than because he is perfect for the role? (The character is not identified as black in the script.)

Adam Flemming’s effective multi-media of photos and placards looked beautiful on the mottled slate-gray walls of Jeffrey R. McLaughlin’s simple set, and stage manager Corey Womack tightened the pace with rapid-fire cue pick-ups. While I agree that there should be music in between scenes (some are so heavy that the audience needs to breathe), sound designer Peter Bayne opted for music that sounded like a soundtrack from a television medical drama.

Adam Flemming’s effective multi-media of photos and placards looked beautiful on the mottled slate-gray walls of Jeffrey R. McLaughlin’s simple set, and stage manager Corey Womack tightened the pace with rapid-fire cue pick-ups. While I agree that there should be music in between scenes (some are so heavy that the audience needs to breathe), sound designer Peter Bayne opted for music that sounded like a soundtrack from a television medical drama.

Those who have never seen The Normal Heart before will be more than happy to be introduced to what I believe is one of the greatest American plays of the last 25 years. It’s an important work which is so well-constructed that even a mixed production could summon tears. And with the filmed version with Julia Roberts and Mark Ruffalo airing on HBO next year, there will be few opportunities to see it live after that (TimeLine Theatre in Chicago is also jumping on board when the play opens in November with director David Cromer starring as Ned). The production at the Fountain is middle-of-the-road due to Levy’s casting inconsistencies and his unfocused direction of the actors. Let’s classify it as “normal” for L.A. theater. I just wish it had more heart.

photos by Ed Krieger

The Normal Heart

Fountain Theatre, 5060 Fountain Ave.

scheduled to end on November 3, 2013

EXTENDED to December 15, 2013

for tickets, call (323) 663-1525 or visit http://www.FountainTheatre.com

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

The music in “The Normal Heart” at the Fountain is original, and Peter Bayne is the composer.

Hello, I am a producer and actor in Brazil and I was very interested in setting up the play The Normal Heart here in my country, could you contact the author Larry Kramer or his agent? Thanks!!

Contact Samuel French (link) to acquire rights to the play, Leandro.