IN GOOD COMPANY

“It’s a revue, but not a revue,” Stephen Sondheim said about Company when he was interviewed at Segerstrom in 2013. This surprised me because the groundbreaking 1970 musical is a concept musical, meaning that the themes of a show (in this case, marriage and commitment) are woven throughout the play, but do not support a plot. Hair (1968) may have set the standard, but Company paved the way for the most successful concept musical of all time: A Chorus Line (1975), which, not without coincidence, was created by Company’s choreographer Michael Bennett.

The revival which opens in an intimate production by Cabrillo Music Theatre this weekend is noteworthy for the company, which has up until now used the 1800-seat Kavli Theatre for its book musical productions. Directed by the amazing Nick DeGruccio, Company plays at the 396-seat Scherr Forum in the Thousand Oaks Civic Arts Plaza through Feb. 8, 2015.

The revival which opens in an intimate production by Cabrillo Music Theatre this weekend is noteworthy for the company, which has up until now used the 1800-seat Kavli Theatre for its book musical productions. Directed by the amazing Nick DeGruccio, Company plays at the 396-seat Scherr Forum in the Thousand Oaks Civic Arts Plaza through Feb. 8, 2015.

There are three other categories of musical theater besides “concept.” One is the “musical comedy,” in which songs are plopped down at will but do not advance the narrative, such as Gershwin’s Girl Crazy (1930) (most modern jukebox musicals also adhere to this framework). Another is the “integrated musical,” in which song, character, and dance blend to tell a story’”the first full-fledged show in this category is Oklahoma! (1943). Sondheim referenced the fourth category, a “revue,” which is a musical show consisting of skits, songs, and dances, often satirizing current events, trends, and personalities (the Ziegfeld Follies is a perfect example, although Maltby and Shire’s Closer Than Ever (1989), which eschewed skits and dances for only self-contained songs, is easily classified as a revue). Considering that Company has elements of a revue, there is no doubt as to why the composer/lyricist refers to his baby as both a revue and non-revue.

Yet Company is simply not a revue because, according to critic Steven Suskin, it broke all the rules of musical dramaturgy, forging a new type of musical’”now known as a concept musical, a term which was devised by The New York Times’ Martin Gottfried in his review of Sondheim’s next show, Follies (1971). Gone’”or should we say altered?’”were plot, narrative, subplots, scenes and scene changes, and the usual method of storytelling. Now, many things were happening at once, with multiple characters in several locations in different locales crowding the stage simultaneously.

Yet Company is simply not a revue because, according to critic Steven Suskin, it broke all the rules of musical dramaturgy, forging a new type of musical’”now known as a concept musical, a term which was devised by The New York Times’ Martin Gottfried in his review of Sondheim’s next show, Follies (1971). Gone’”or should we say altered?’”were plot, narrative, subplots, scenes and scene changes, and the usual method of storytelling. Now, many things were happening at once, with multiple characters in several locations in different locales crowding the stage simultaneously.

The show was a hit, running for 706 performances, and was nominated for a record-setting fourteen Tony Awards, winning six. The mixed reviews were due to George Furth’s freestyle libretto of sketch-like fragments not matching the quality, tang, sophistication, and intelligent wit of his collaborator (I maintain that Furth’s unnecessarily scathing and cynical book for Merrily We Roll Along (1981) is the reason that musical is so difficult to produce well.) Ultimately, Company was only one of two shows that were financially successful for the team of Sondheim and director Hal Prince; the other monetary success of their six collaborations was A Little Night Music (1973). (Surprisingly, Sweeney Todd [1979], Sondheim’s artistic apotheosis, scared away tourists and bled its producers dry.)

The show was a hit, running for 706 performances, and was nominated for a record-setting fourteen Tony Awards, winning six. The mixed reviews were due to George Furth’s freestyle libretto of sketch-like fragments not matching the quality, tang, sophistication, and intelligent wit of his collaborator (I maintain that Furth’s unnecessarily scathing and cynical book for Merrily We Roll Along (1981) is the reason that musical is so difficult to produce well.) Ultimately, Company was only one of two shows that were financially successful for the team of Sondheim and director Hal Prince; the other monetary success of their six collaborations was A Little Night Music (1973). (Surprisingly, Sweeney Todd [1979], Sondheim’s artistic apotheosis, scared away tourists and bled its producers dry.)

Sondheim stated in the PBS special Broadway: The American Musical that in 1970 Broadway theater had been supported by upper-middle-class people with upper-middle-class problems. Those same people who really wanted to escape that world when they went to the theatre would have it thrust right back in their faces when they attended Company.

Sondheim stated in the PBS special Broadway: The American Musical that in 1970 Broadway theater had been supported by upper-middle-class people with upper-middle-class problems. Those same people who really wanted to escape that world when they went to the theatre would have it thrust right back in their faces when they attended Company.

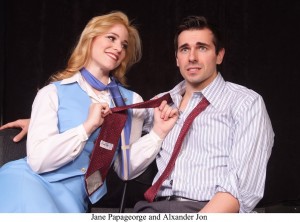

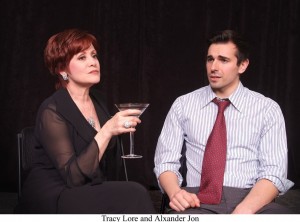

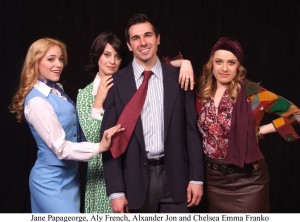

The upper-middle-class people in Company that Sondheim spoke of are one engaged couple and four married New York couples, all characters that were born from an unproduced Furth evening of eleven unconnected one-acts written for actress Kim Stanley. It was Prince’s idea to develop a central character, their best friend Robert (played at Cabrillo by Alxander Jon), a commitment-phobic single man who is used as a tool to examine these marriages.

The upper-middle-class people in Company that Sondheim spoke of are one engaged couple and four married New York couples, all characters that were born from an unproduced Furth evening of eleven unconnected one-acts written for actress Kim Stanley. It was Prince’s idea to develop a central character, their best friend Robert (played at Cabrillo by Alxander Jon), a commitment-phobic single man who is used as a tool to examine these marriages.

Also added were three girlfriends, April, Marta and Kathy, who sing the delightful “You Could Drive a Person Crazy.” The vignettes, presented in no particular chronological order, are linked by a party thrown for Bobby’s 35th birthday. If the show is cynical and jaded at times, it’s ultimately about the fact that people matter in your life.

Also added were three girlfriends, April, Marta and Kathy, who sing the delightful “You Could Drive a Person Crazy.” The vignettes, presented in no particular chronological order, are linked by a party thrown for Bobby’s 35th birthday. If the show is cynical and jaded at times, it’s ultimately about the fact that people matter in your life.

Sondheim’s indelible score refuses to fade, remaining bright, vibrant, clever, funny, sardonic and intelligent. Notable and enduring songs include “Ladies Who Lunch,” “Sorry/Grateful,” “I’m Not Getting Married,” “Another Hundred People” and “Being Alive.”

Sondheim’s indelible score refuses to fade, remaining bright, vibrant, clever, funny, sardonic and intelligent. Notable and enduring songs include “Ladies Who Lunch,” “Sorry/Grateful,” “I’m Not Getting Married,” “Another Hundred People” and “Being Alive.”

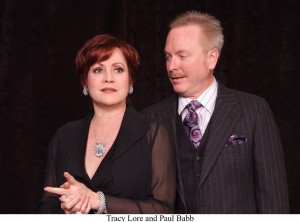

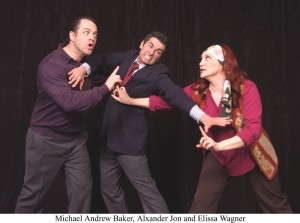

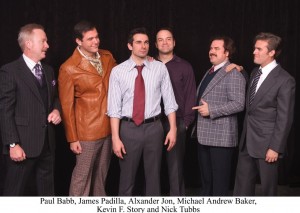

With musical direction by Cassie Nickols, and choreography by Cate Caplin, Cabrillo’s cast includes this year’s Ovation Award Winner Tracy Lore (“Joanne”), Michael Andrew Baker (“Harry”), Nick Tubbs (“Paul”), Shelley Regner (“Amy”), Elissa Wagner (“Sarah”), and Paul Babb (“Larry”). Other cast members include Heather Dudenbostel, Chelsea Emma Franko, Aly French, James Padilla, Jane Papageorge, Elizabeth Smith, and Kevin Story.

Company

Cabrillo Music Theatre

Scherr Forum at Thousand Oaks Civic Arts Plaza

2100 Thousand Oaks Boulevard in Thousand Oaks

Thurs at 7:30; Fri at 8; Sat at 2 & 8; Sun at 2

plays January 23 thru February 8, 2015

for tickets, call 800-745-3000 or 805-449-2787

or visit www.CabrilloMusicTheatre.com