A DELIVERANCE IN DACHAU

Even in the Holocaust’s democracy of death each victim could only die once. But some seem to have died a bit less than others. Remembering the unnumbered thousands of homosexuals killed by Nazi hate more than the six million Jews slaughtered, Martin Sherman’s still-stirring 1979 drama sums up many losses in three sharply-captured lives and deaths. Amid the carnage, Bent chronicles a strange gain. This sincere but uneven, barebones revival by The Other Theatre Company (who specialize in plays excoriating human oppression) shows how Max, a handsome, hedonistic, cocaine-snorting homosexual, learns to love in a world wild with evil. This is the other side of Cabaret, with no Kit Kat Klub to distract us from Hitler’s gaping genocide, just Sherman’s increasingly empty gallows humor.

The playwright spares no sensibilities in his lean, graphic depiction of same-sex survivors caught up in the Holocaust. As if making up for past silence on the subject, each scene hits like a body blow: Max, a feckless Berlin party boy and drug-user, and Rudy, his delicate dancer boyfriend, encounter instant hell: Private lives connect with public events: Bent begins in 1934, on the Night of the Long Knives, when Hitler purged Ernst Röhm and the SA from the military. Tough Max (Nik Kourtis) and his quondam lover Rudy (Will Von Vogt), whose name he will forget, find themselves suddenly engulfed in history, barely escaping arrest.

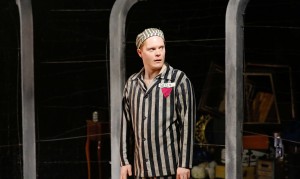

Together with this delicate dancer who cannot fathom mindless cruelty, Max flees their supposedly safe life to a forest (which city boy Rudy keeps calling a “jungle”) where, arrested, they’re thrown onto a death train to Dachau. Driven not to die, Max cuts ever more despicable deals to save his skin. (As another imprisoned homosexual projected, “Yet each man kills the thing he loves.”) He will sell anything he can to lose what little honor he had. Though not Jewish, to curry respect from the other prisoners he wears the yellow star of David, not the gay-identifying pink triangle, and bribes the guards to let him carry rocks, a torture worthy of Sisyphus.

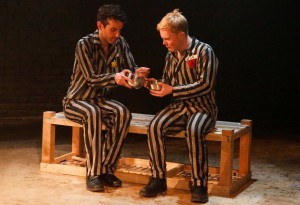

When Horst (Alex Weisman), a former nurse, taunts Max for denying his sexuality and aping his enemies, Max slowly learns to care for another, a love that even grows from lack of sex. (In a famous scene they do, however, make love without touching.) Though Sherman often tries to shock and amuse in the same scene (the incongruous humor reaches a low when Horst begs Max off with “I have a headache”), the play slowly slows down and sobers up. It seems a lot less like Mort Crowley’s infamous Boys in the Band as it challenges us with the same taunt: Gays don’t deserve t0 be loved.

Like the still-haunting killing fields of AIDS, the agony of a death camp tests the full bent of its victims, a sacrificial parallel suggested by Keira Fromm’s concentrated staging. As they carry rocks back and forth across the stage, Max and Horst seem both spin-offs from a very sick Waiting for Godot and living witnesses to a crime against humanity, not a crime against nature. They end as human sacrifices intended to claim dignity amid death. Alas, their final moments could easily seem empty, Hollywood gestures, meant for the audience more than the prisoners. Unfortunately, that seems the case in this revival–more than previous Bents I’ve endured where vulnerability wasn’t concealed by cuteness.

Playing Max’s tender and doomed lover, Von Vogt endears as gentle, fragile Rudy. Weisman at times seems upright with Horst’s rough love for a chastened Max, though in the next moment his ugly mockery seems to discount Max’s demeaning suffering. Regrettably, though Kourtis registers Max’s almost contagious self-doubt, he establishes neither Max’s feckless promiscuity nor his later redemptive devotion. More problematic is Weisman’s flippantly sarcastic soulmate: His splenetic petulance spoils the pathos of the protracted final scenes. (The tedium of their torture comes through all too well.)

Too often in this 140-minute straightforward Bent the complexity of conflicting loyalties is sacrificed to easily accessible emotions, though Stephen Rader as Max’s cold and closeted uncle drives home the betrayal of the divided and conquered. He’d rather cruise a “fluff” in the park than rescue his nephew. That act indicts as much as the Gestapo’s systematic cruelty. Of course, Stonewall was still a generation ahead and a Supreme Court decision two generations later.

photos by Carin Silkaitis

Bent

The Other Theatre Company

Strawdog Theatre, 3829 N. Broadway

Wed & Fri at 8; Sat at 4 & 8; Sun at 4

ends on July 26, 2015

for tickets, visit BuzzonStage

for more info, visit www.theothertheatrecompany.com

for info on more Chicago Theater, visit www.TheatreinChicago.com