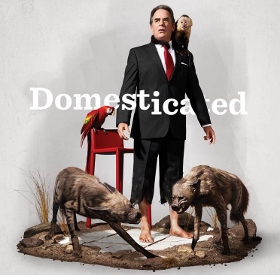

A POUND OF LOVE EXPLODES INTO A TON OF HATE

Short of screaming “Fire!” in the theatrical darkness, you can’t imagine a more polemical provocation than Domesticated. As with Grand Concourse and Good People, Steppenwolf Theatre Company delivers another gadfly masterpiece with this Chicago premiere. There’s toxic irony in the title of Domesticated, a demure euphemism for some less pleasant adjectives about the taming of a husband. (You know what they are.)

The 155 minutes of director/author Bruce Norris’s latest detonation amount to a choose-your-side potboiler. It crystallizes and anatomizes the war between the sexes. Norris boils down eons of gender friction and mating misery into a very dysfunctional, graphically messed-up marriage. Seen from all sides, it’s cruelty up close, love gone rabid. No question, Domesticated will incite controversial post-show conflicts, if not divorces. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

The opening leaves no doubt about the indictments to come’”or the theme that Norris pursues like a demented bloodhound. It’s an illustrated lecture in a school gym, presented by an otherwise mute teenager who details the superiority of the females of other species in reproduction and rearing. (But what, we ask, about humans?) Next comes the meat of the matter: A former gynecologist known as “The Pulverizer” in college sports, government honcho Bill Pulver (Tim Irwin, both cowed and contemptuous) stands with his sternly impassive, 50-year-old wife Judy (Mary Beth Fisher, a marvel of dry disdain) before a microphone. Almost incoherently, Bill resigns his prominent position. Yes, dour Judy stands by her man’”but here that’s only literal. Bad Bill has been caught in a sex scandal that looks like attempted murder: In the latest of many acts of infidelity (37 trysts over 10 years costing $74,000), this philanderer is accused of striking the sex worker who was servicing him: 23-year-old, 105-pound Becky hit the floor and is now in a coma.

The opening leaves no doubt about the indictments to come’”or the theme that Norris pursues like a demented bloodhound. It’s an illustrated lecture in a school gym, presented by an otherwise mute teenager who details the superiority of the females of other species in reproduction and rearing. (But what, we ask, about humans?) Next comes the meat of the matter: A former gynecologist known as “The Pulverizer” in college sports, government honcho Bill Pulver (Tim Irwin, both cowed and contemptuous) stands with his sternly impassive, 50-year-old wife Judy (Mary Beth Fisher, a marvel of dry disdain) before a microphone. Almost incoherently, Bill resigns his prominent position. Yes, dour Judy stands by her man’”but here that’s only literal. Bad Bill has been caught in a sex scandal that looks like attempted murder: In the latest of many acts of infidelity (37 trysts over 10 years costing $74,000), this philanderer is accused of striking the sex worker who was servicing him: 23-year-old, 105-pound Becky hit the floor and is now in a coma.

This begins a tailspin of misfortune told with video, rapid set changes and gobs of cunning acting. Bill’s fall is rapid and rancid. Engulfed in notoriety, this shamed loser has understandable trouble resuming his work as a gynecologist. The inevitable divorce and punishing settlements force Bill to sell their beloved summer home in Brittany and to seek an apartment that can’t be too tiny for Judy’s taste. Bill almost loses an eye when he’s attacked by a transgendered Amazon, struck for denying that she could be a woman. (In Bill’s case that’s not an insult.)

Caught in the family crossfire, Bill’s daughters make their separate cases. Adopted from Cambodia, soft-spoken Cassidy (Emily Chang) dispassionately describes the superiority of females in mating and child-rearing. Rebellious and resentful, Casey (Melanie Neilan) is consumed with a rage against penises and crusades against the cultural savagery of customs like genital mutilation. Rigid with sisterly solidarity, they don’t want to see or hear their damaged dad.

Almost 90% of the first act’s dialogue belongs to the women characters. (The cast confirms the beat down–two male actors in a cast of fifteen.) They present every possible position on misandry and misogyny, ranging from old-school acceptance of husbands’ delusions of entitlement to a Muslim woman’s volatile mix of sexual martyrdom and ready bigotry to concerns about how best to police monogamy. Bill’s betrayal even involves the brilliant lawyer who defends him (supple Beth Lacke) and who, lamentably, happens to be his wife’s best friend. Bill’s one happy memory of what seemed like love’”how, plucking a guitar, he serenaded his coed sweetheart beneath her balcony’”morphs into one more reason for revenge.

But all this changes radically at the top of the second act: Irwin’s supposed victim now makes a male-centric case for his crimes against marriage. A play that had been a one-sided denunciation and feeding frenzy against a sexist pig slowly becomes a painfully nuanced debate. Rampaging against the institution that he was sentenced to (for him marriage means “restriction, reproduction and real estate”), Norris’s all-too-representative male protagonist argues that the tables have been turned. Justly or not, men have lost the sway they used to abuse creatures they once controlled. Patriarchs everywhere have had their balls busted and their backsides whipped by wily women with the power to give life where men can only take life. Driven nurturers, women used the lure of sex and the illusion of love to achieve their real goal’”a baby who then receives the woman’s true love, not the simulation of passion that she used to seduce this necessary evil, the sperm bearer. The spousal inseminator has served his purpose. Benevolently or sadistically, the wife/mother keeps him around to raise the crucial offspring. But, if the wretch wanders into adultery, he’s cast out of Paradise, destined for alimony and heartbreak.

It’s up to the audience to choose between Domesticated’s feminist first part and its revisionist second part. More specifically, the question of whether Bill shoved Becky or if it was just a sad mishap remains artfully unanswered (and ultimately dismissed). It’s not the prosecution that Norris intends. Bracing, infuriating, hilarious and deeply disturbing, Domesticated is a theatrical thrill ride. It’s no accident that the book Judy writes about her humiliating marriage is called “You Have To Be This Tall.” A dramatic roller-coaster, Norris’s declaration of independence asks no less of its target audience.

photos by Michael Brosilow

Domesticated

Steppenwolf Theatre Company

Downstairs Theater, 1650 N Halsted St

ends on February 7, 2016

for tickets, call 312.335.1650 or visit Steppenwolf

for info on more Chicago Theater, visit Theatre in Chicago