A KURT WEILL COMEBACK

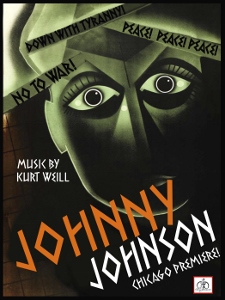

Here’s another triumph worth the wait. Recently revived, City Lit’s London Assurance took 120 years to return’”hilariously’”to a Chicago stage. Even more inexplicably absent and a much more recent treasure, Kurt Weill’s 1936 anti-war musical Johnny Johnson has never played the town till now. With libretto and lyrics by Paul Green, this engrossing full-length musical, now in a new edition edited by Gerald Frantzen, is richly and warmly presented at Stage 773 by Chicago Folks Operetta.

Relishing the restoration of original orchestrations and captivating scores, this meticulously marvelous company lovingly preserves and produces unjustly neglected treasures of their genre. Wondrously shaped by director George Cederquist, the 150-minute result is a “blast from the past” time capsule to evoke an era and to simultaneously delight eyes, ears, minds and souls.

The Kurt Weill we hear here is halfway between his raunchy Weimar period (Brechtian rousers Threepenny Opera, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, Happy End) and his Broadway box-office busters (One Touch of Venus, Lost in the Stars, Knickerbocker Holiday). Happily, it’s got the best of both’”lilting, saxophone-drenched ballads, peppy anthems, mood-setting melodies that double as gorgeous underscoring, and fiery agitprop, drum-rolling mockeries of military pomposity and jingoistic overkill.

Created for Lee Strasberg’s socialist-minded Group Theatre, Johnny Johnson (its name taken from the most commonly found names on the rolls of the dead) was inspired by and drawn from Jaroslav Hasek’s The Good Soldier Schweik, a still invaluable satire of one soldier’s desperate attempts to stay sane in a world gone mad. The Group’s antihero is 26-year-old Johnny Johnson (a plaintive Gabriel di Gennaro), an idealistic patriot and sculptor who in the first scene carves a monument to Peace and romances the fickle Minny Belle (Kaitlin Galetti).

Suddenly, just as Woodrow Wilson declares “a war to end all war” (a phrase that Johnny appears to have invented), his pacifist town (which includes one very strange bearded lady) abruptly changes course: Reeling with false patriotism, they’re eager to die for democracy (or, at least, to sacrifice their sons). Johnny’s romantic rival Anguish Howton (Joshua Smith), a purveyor of poisonous mineral water, turns slacker and draft dodger (allowing him to stay behind and steal away faithless Minny). But true-blue Johnny enlists, endures soul-shrinking basic training, and ships off for the trenches of France. As he quits our shores, an animated Statue of Liberty (Christine Steyer) seems to bless him (and will do so, with more reason and feeling, when he returns).

“Over there,” Johnny becomes a popular G.I., initially enraptured by this grand adventure. But when he captures’”and refuses to kill’”a 16-year-old German sniper (Joseph Frantzen), he turns against the mindless massacres and competitive blood-letting of both sides. Preferring laughing gas to mustard gas, Johnny brings the war to a temporary halt by paralyzing with pleasure a rogues’ gallery of battle-bitter generals.

Johnny’s brief and doomed attempt at an armistice earns him a Section 2, sending him to a mental hospital for a ten-year “treatment.” (Weill would take a very different attitude to psychiatry in Lady in the Dark.) No hometown hero, when Johnny comes back to Everytown USA, the tested veteran discovers that peace is as elusive as ever. Undeterred, he exploits his talent for making toys’”but refuses to sell tin soldiers to future casualties. In a final glorious reprise (simply called “Johnny’s Melody”), he and an approving Statue of Liberty literally enlighten the future. (Of course, just three years later an equally stupid and wasteful war will surpass the “Great” one. Johnny Johnson was just an artistic bump in the road to another call to arms.)

It’s frustrating to use mere language to describe Weill’s deeply moving, dynamically diverse score. Don’t take my words for it. You could as easily capture it in the feelings it triggers as the styles he adopts. These include a tango, a cowboy pastiche, a pulsating “Song of the Guns,” a passionate “Hymn to Peace” contrasted with the bellicose “Democracy’s Call,” even a patter-like travesty in “The Psychiatry Song.”

Superbly conducted by Anthony Barrese and an unimprovable 12-person orchestra, each of almost 30 songs pulls its weight and engages head and heart. Playing sandwich-board generals, lollipop-licking prelates, very public privates, or gentle mental patients on Eric Luchen’s supple sets, the 15-member cast teems with terrific singers, able at any moment to create one perfect voice or to suggest all the shell-socked anarchy of “over the top” war fever.

Kudos to everyone connected with this noble venture! An artistic achievement to merit unstinting and unconditional praise, C.F.O.’s Johnny Johnson is a golden (re)discovery, a magnificent reclamation of a brilliant composer’s enthralling cry for justice and peace. See (and hear) it!

photos courtesy of Chicago Folks Operetta

Johnny Johnson

Chicago Folks Operetta

Stage 773, 1225 W. Belmont Ave.

Thurs-Sat at 7:30; Sun at 2

ends on July 9, 2017

for tickets, visit Chicago Folks Operetta

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

My favorite reviewer on my favorite composer. I must see this again.