’˜SELF DEPORTATION’ OR SIX STAGES

OF AMERICAN GRIEF

Denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. In life, death, and in playwright Tom Jacobson’s world view, these familiar five stages to acceptance are missing the one that is most important for survival: Laughing. Life is funny. People are funny. If God exists, He, She, They, or It must have a sense of humor’”however twisted and brutal.

The “shattering comedy” Jacobson promises in the press notes for Walking to Buchenwald sneaks up on you. The play opens with a series of scenes of an elderly couple, Mildred and Roger (Laura James and Ben Martin) resisting their daughter Schiller (Mandy Schneider) as she tries to bully them into a sort of European Trip of the End of a Lifetime. She makes it sound about as fun as a school field trip, and it looks like neither parent, then perhaps only her father, Roger, will agree to go. Schiller’s partner Arjay (Amielynn Abellera) has more luck. Her warm friendship with Schiller’s mother seems to be the persuasive touch needed to get the recalcitrant Mildred on board.

As the four of them embark on their travels, Jacobson boldly allows the experience to feel at first almost as interminable for the audience as such trips can be for some if not most families. Every irritant is regarded as a personal slight, and the response to most disappointments is some variation of “Everything happens to me.” Schiller’s high-strung insistence on micro-managing everyone grows as grating to us as it does for her parents and girlfriend.

But something keeps us riveted. We know Jacobson has a deeper story simmering. He uses no narrative or character shortcuts to stack the deck. No one does anything unexpectedly endearing or silly. No one’s idiosyncrasies explain away his or her annoying habits. No one emerges as conventionally likeable, and the family-based plot twists are effective if not unexpected, any more than they are in life. The four main characters don’t even get most of the laughs. Those belong to an actor in multiple, multinational roles (Will Bradley).

The fractured core of the show’s universe reveals itself gradually. Naturalistic scenes and behaviors take on increasingly surrealistic elements. We start to wonder what exactly is going on. Is this the end of the world? Figuratively, the answer is yes. Literally? We’re not sure. But all bets are off. And yet’¦ somehow, in a final, quiet, awful, loving gesture of human generosity, Jacobson gives us hope’”and a lot to think about.

Buchenwald is about identity. It takes a wide, nonjudgmental look at what it means to be a parent, a spouse, a child; what it feels like to be in a relationship with a partner who is your temperamental opposite; to be a liberal in a Red State; an American in a Trump-like western world; someone dying in a world obsessed with hollow positivity; and what it means to be a European shackled to an America teeming with reemerging nativism.

Jacobson doesn’t seek to determine who is to blame for anything. None of us is to blame. All of us are to blame. Blame God. Whatever. This is our world. The way we live now, and the way we die. Buchenwald lingers long after the final curtain, its puzzles working their way into your dreams.

Jacobson doesn’t seek to determine who is to blame for anything. None of us is to blame. All of us are to blame. Blame God. Whatever. This is our world. The way we live now, and the way we die. Buchenwald lingers long after the final curtain, its puzzles working their way into your dreams.

Open Fist confidently launches this world premiere with a terrific cast. Will Bradley does a star turn in the Jefferson Mays, A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder vein. With a dizzying array of accents and personal quirks, he knowingly portrays all the minor characters. Bradley’s performance is a tour de force in gorgeous miniature. He shows us not just how Europeans view Americans, but how we view ourselves.

Laura James is a veteran actress with a gruff exterior and a disarming delicacy. She never limits herself to the curmudgeonly aspects of Mildred, finding buoyancy and humor in unexpected places. Ben Martin starts off playing Roger as an affable former professor who goes along to get along, before ably plumbing the depths of a man whose entire way of life is disappearing. Amielynn Abellera and Mandy Schneider are believable and persuasive, though Schneider could afford to dial back the character’s desperation to control every situation.

Roderick Menzies directs with an invisible hand, never calling attention to himself. He trusts his actors, but my sense is that he is guiding them more firmly than they realize, for the performances meld into a singular force with a symbiotic power.

In this play, as in other projects, Jacobson enjoys exploring gender fluidity. On alternate performances, the lesbian couple here becomes a gay male couple, played by Justin Huen and Chris Cappiello’”or you may see a heterosexual couple. It’s an interesting idea, that speaks to the mutability of seemingly immutable character elements. It’s also not a bad marketing ploy. I might just get a ticket to see the show again.

photos by Darrett Sanders

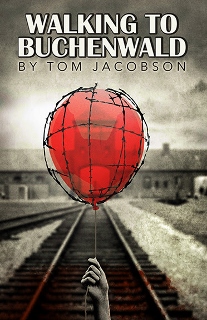

Walking to Buchenwald

Open Fist Theatre Company

Atwater Village Theatre, 3269 Casitas Ave

Thurs-Sat at 8; Sun at 7

ends on October 14, 2017

for tickets, call 323.882.6912 or visit Open Fist