DON’T MYTH OUT,

OR DANCING THAT’S ORPH THE CHARTS

LA Opera’s gorgeous production of Christoph Willibald Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice (Orphée et Eurydice), featuring a welcome collaboration with the Staatsoper Hamburg and Chicago’s Lyric Opera (with the Hamburg and Joffrey Ballets), lives up to the hype, hope, and expectation it has generated since its announcement.

LA Opera’s gorgeous production of Christoph Willibald Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice (Orphée et Eurydice), featuring a welcome collaboration with the Staatsoper Hamburg and Chicago’s Lyric Opera (with the Hamburg and Joffrey Ballets), lives up to the hype, hope, and expectation it has generated since its announcement.

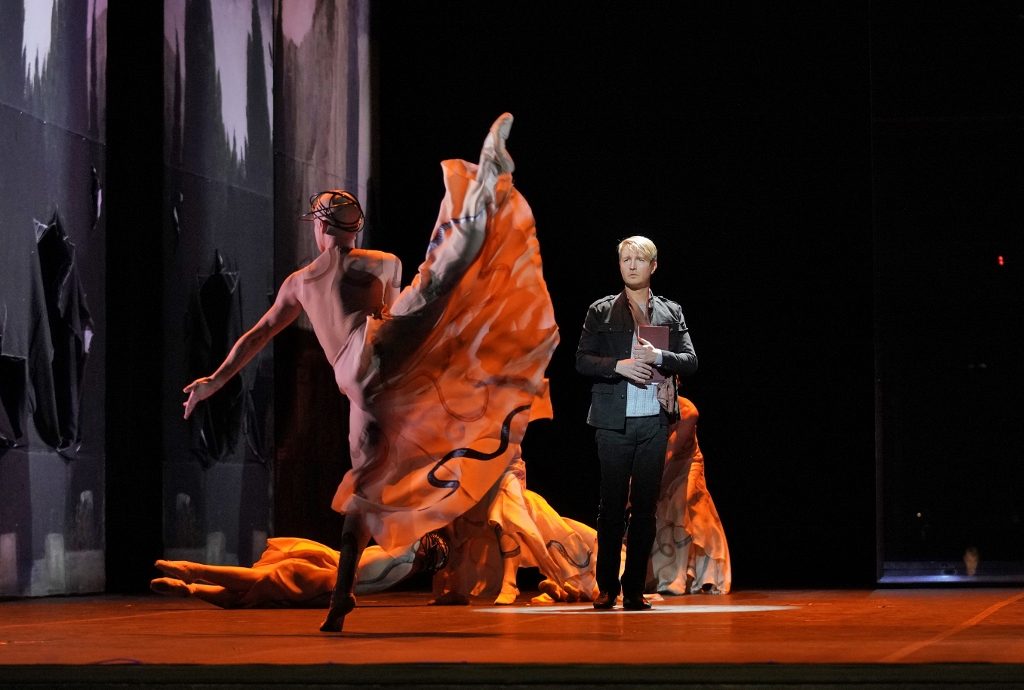

Gluck’s 1774 French version of his earlier 1762 Italian opera only has three character roles (performed here by the outstanding Maxim Mironov, Lisette Oropesa, and Liv Redpath) and, along with generous choral work, has large sections of music meant for dance. So who better than John Neumeier to take the reins as director for a new production? At a time when many ballet companies are commissioning short dance pieces, it’s refreshing that Neumeier — since he became Artistic Director and chief choreographer of the Hamburg Ballett in 1973 — continues to develop story ballets. While his all-encompassing vision as director, choreographer, and costume, set and lighting designer left a few elements lacking in conception and storytelling, which is a bit incoherent, his leads and his dancemaking — executed by the glorious Joffrey movement artists — are phenomenal.

Based on the Greek myth of the same name, Gluck’s Orphée tells the tale of the famous musician and poet who descends to the underworld and charms the furies in order to take his wife Eurydice back from the grave. The arc of the three acts take us from death to life in this world and on through the realms of Hades and the Elysian Fields. Besides the titular characters, librettist Pierre-Louis Moline (after Ranieri de’ Calzabigi’s original in Italian) names only one other: Amour, or Cupid, whose suggestion propels Orphée to seek Eurydice among the dead, with the sole condition that he not look at her.

Inspired by Swiss symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin’s classic Isle of the Dead (1880), Neumeier’s vision brings this timeless tale to the present day: Gluck’s exuberant overture, which is sometimes cut, is accompanied onstage by a ballet rehearsal. Orphée, a choreographer, quarrels with his ballerina wife who has arrived late. Eurydice leaves in a fury after slapping him in front of the company and fatally crashes her Mini Cooper into a tree (by contrast, the libretto is silent on the details of Eurydice’s death). Orphée’s assistant (Amour) offers solace with the ancient Greek tale, but warns he must not look at his beloved in the face till they’re back on earth. He gets into the underworld and finds his wife, who is upset that he doesn’t gaze upon her. When he does, she goes back to the dead, and he designs a ballet in her memory.

Neumeier’s inventions here and elsewhere don’t always illuminate the original story: All we know of his wife is that she’s an unlikable temperamental diva; why, then, is he so stricken with grief? (Her irascibility makes sense when she later gives Orphée hell in heaven.) And how does Orphée calm the furies and gain access to his beloved if he is not a musician? — for nowhere is it alternatively suggested that Orphée charms them with his choreography (though he will definitely win over LA Opera audiences!). Well, one look at the synopsis, and we will learn that Orphée is experiencing grief-induced madness and that this is all a dream.

While things are a little myth-placed, if you will, as a whole Neumeier’s production enthralls with the beauty of the music and dance. His mostly monochrome fragmentary sets (realized with Heinrich Tröger) tend to the abstract and don’t quite suggest the horrors of Hades or the euphoria of the Elysian Fields. Much of the movement, especially in Act II, is achieved through rotating, interchangeable configurations of walls, doors, mirrors, and windows — it’s not a wrong choice, but definitely designed for dancing not grand opera.

Of the dancer’s costumes, those of the furies are the most interesting and effective: Three look like algae-encrusted creatures who have slithered out of the river Styx, and the corps de ballet in flowing skirts and tight tops suggest wraiths. Later, the lightweight, white material for Elysium is a variation of Greek togas. Eurydice wears a number of flattering dresses, and she often appears shrouded in a wedding veil, even after her return from the dead (in the original, the star-crossed lovers were just married; there’s no suggestion of that here, although Orphée does have a brief remembrance of their wedding day). Amour is now a trouser role, and she’s dressed in a hoodie and jacket as if she’s on a pleasant fall hike — Amour’s loveliness is projected only by the beautiful Liv Redpath.

The best part and most enjoyable part of this production, besides Gluck’s superb score, is the huge cast. Renowned Russian tenor Maxim Mironov has a fittingly fluent and fantastic voice for the role of the fabled hero, singing with svelte soulfulness and sincerity. His interpretation remained at all times measured and melodious, even during the celebrated cadenza at the first act climax. Opposite him, first generation Cuban American soprano Lisette Oropesa played the part of Eurydice with grace and beauty, her voice blending sweetly with Mironov’s in the delicious duets of Act III. A Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artist Program member, Ms. Redpath sings with worthy strength and flexibility as the choreographer’s assistant, a.k.a. God of Love.

The evening would not have been possible without the Joffrey Ballet, which is featured just as prominently on stage as the singers. The interplay of song and dance makes this a delightfully diversified entertainment, as does the alternation of soloists and chorus, though the latter remains hidden in the pit throughout. Under Grant Gershon’s sterling direction, their hymn-like singing — combined with Gluck’s rich harmonies — gives the opera a sacred aura, which meshes well with the divine talent of the titular hero and his journey to the heavenly realm.

The combination of Joffrey Principals Victoria Jaiani and Temur Suluashvili’s grace and strength during “Dance of the Blessed Spir its” for flute and strings, which has become one of Gluck’s most pop u lar instru men tal works, is luscious, enchanting, and culture of the highest order.

Neumeier’s vision may distract a bit, but — under the superb baton of James Conlon in one of his best efforts — it does not prevent the enjoyment of this delightful, timeless French opera, one that pre-dates the usual LA Opera fare.

Orphée et Eurydice (Orpheus and Eurydice)

LA Opera

co-production with Lyric Opera of Chicago, Joffrey and Hamburg Ballets

Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, 135 North Grand Ave

ends on March 25, 2018

for tickets, call 213.972.8001 or visit LA Opera