JOFFREY STEPS OUT OF A DREAM,

OR DELUSIONS OF A SCANDINAVIAN SOLSTICE

First, a necessary clarification for A Midsummer Night’s Dream: The title and the setting could easily confuse lovers of, respectively, William Shakespeare and Ingmar Bergman. A Midsummer Night’s Dream is not a ballet version of the former’s quicksilver 1595 comedy of rearranged lovers and quarreling fairies. (And there is absolutely no Mendelssohn.) Though the setting is rural Sweden, it’s equally not a treatment of the latter’s Smiles of a Summer Night, the enthralling 1955 film that became Stephen Sondheim’s A Little Night Music.

Indeed, it’s easier to say what Joffrey Ballet’s season-closer at the Auditorium Theatre is not. This is a puzzlement wrapped in some very pretty and sometimes scary pictures.

The occasion is the North American premiere of a 2015 work by noted Swedish choreographer Alexander Ekman (creator of Joy and Episode 31). His “dream” is a very communal (at times, delusional) celebration of what could be Sweden’s national holiday. Unleashed on whatever Friday happens between June 19 and 25, it’s the annual midsummer romp, marking the year’s longest day (and, significantly, shortest night).

But however brief the darkness, on this vast stage it’s pregnant with possibilities, all cavorted to an indie rock/New Age score by Swedish composer Mikael Karlsson and frenetically performed by members of the Chicago Philharmonic. It also features Swedish rock vocalist Anna von Hausswolff: An Enya-like troubadour, von Hausswollff croons three Euro pop songs that could have come straight from Cirque du Soleil.

The key word — one that explains, if not excuses, a lot — is dream. This is The Wizard of Oz, this time with us knowing from the start that it’s Dorothy’s dream. So it doesn’t have to make sense, the last thing we demand from our nocturnal travels. As it is, for Swedes the summer solstice is already a mass hallucination — a mysterious and romantic celebration of fecundity, both human and natural. It’s fueled by fantasies enshrined in folklore, and dances to celebrate the midnight sun. Rationality is irrelevant.

Ekman pulls out all the stops to deliver the delirium of a dream wedded to the greenery, brilliant bonfires, and maypole (the midsummer pole) of June 24, feast day of St. John the Baptist.

You can tell this ain’t your usual Terpsichorean enchantment: Before the exuberance even begins, we see projected slogans, saying “Sven is drunk,” “Welcome to Sweden,” and, prophetically, “I’d rather be somewhere else” (which unimpressed patrons saw as an excuse to leave early before the second act).

Exploiting the supposed magic of the year’s solar peak, Nordic folks gather herbs and nine different kinds of wildflowers, dance the SmÃ¥ Grodorna around the poles, play bag-jumping and tugs of war, indulge in literal rolls in the hay, dine outdoors on very long, candlelit tables (and, no doubt, Swedish meatballs), and sing about small frogs. (I am not making this up.)

But here these daily doings and nightly revels are part of a reve: The action is no more important than the arbitrary happenings we briefly recall when we wake up in the middle of one. Ekman’s Fête champêtre delivers no conflict, only custom, no logic, only lunacy. In his “transformative storytelling” (except there’s no story) and “fully immersive theatrical experience” (well, yes, if you watch it from on stage), we’re regaled in the first act with the vast Joffrey corps de ballet in full frolic. Ecstatically, they toss hay in the air and at each other, unfurl umbrellas against sudden tempests, crowd the stage apron to toast the awkward audience, and listen in fascination to the constant chirping of a very persistent songbird (no credit given).

With its harvest dances, giant hay crosses, and village banquets, the shorter first act seems comparatively calm: Teeming with tableaux but no plot, it ends with the performers gently transporting candelabra into the house.

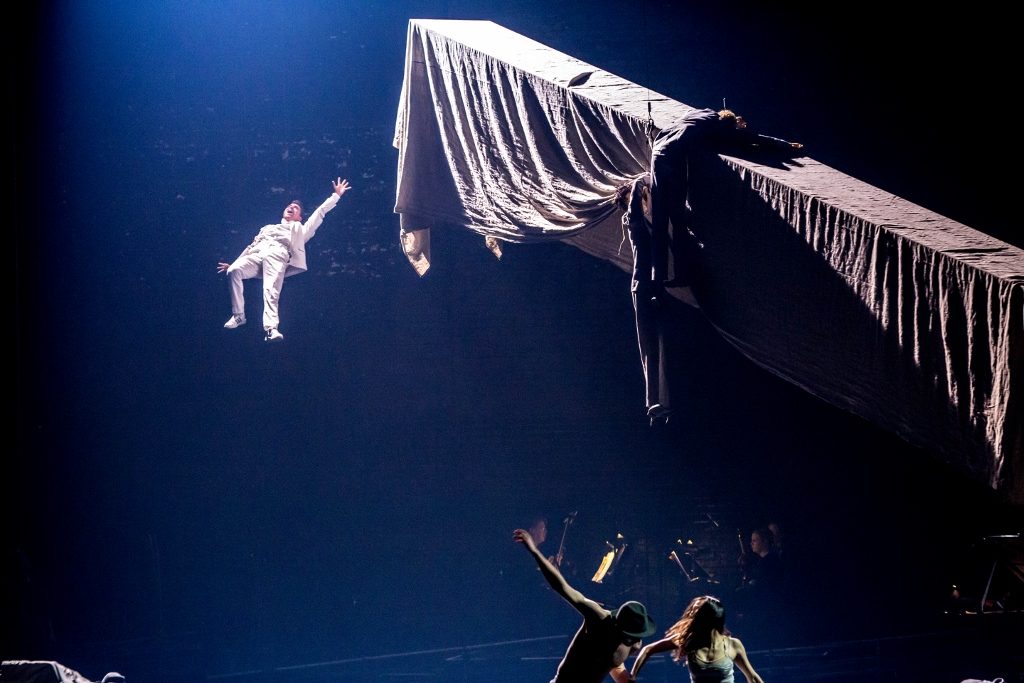

But, along with an intermission, night is coming and, with it, dangerous dreams within this dream. Diving off its own deep end, in the second act the dream turns contagiously surreal, Dali- and Chagall-style. The bed that contained the chief dreamer (Temur Suluashvili) suddenly soars, happily empty. The long tavern tables of the first act also lift up, discarding the dummy drinkers and sending another into a “Flying by Foy” free fall. We see a man (Fabrice Calmels) furiously flailing a flag, another bearing the almost unnecessary placard “THEATER DREAM.” Two headless men (Edson Barbosa and Elivelton Tomazi) busily haunt the proceedings. Animal imagery abounds.

Karlsson’s score, which in the first act almost sounded weirdly Middle Eastern, now takes up African drumming. Nearly nude (Bregje van Balen’s costumes run the gamut from peasant garb to next to none), the midsummer fools proceed to process, march, ogle, convulse — all but copulate as upside-down trees descend and the world goes topsy-turvy. Never has anarchy been so closely coordinated. At the very end the dream rekindles itself. Notwithstanding the solstice, this day will see no dawn.

It would be easy to dismiss this Midsummer Night’s Dream as so much Scandinavian silliness, Strindberg on steroids. It’s just as possible to cherish it as a splendid simulation of authentic daydreams and nightmares, as close as dance dares to go. Much depends on how much you prefer waking visions and aural actuality to the nocturnal variety.

But there’s no denying the enormous discipline and precise make-believe that went into this very wet dream. Staged by Preston McBain, Marie-Louise Sid Sylwander, and Joakim Stephenson, the 140-minute spectacle reminds me of what William S. Gilbert said to hide the fact that he fell asleep during a long oratorio by his famous partner Sullivan: “My dear Arthur, I was transported to another world.”

photos by Cheryl Mann

Midsummer Night’s Dream

The Joffrey Ballet

Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University, 50 E. Congress Parkway

ends on May 6, 2018

for tickets, call 312.386.8905 or visit Joffrey

for more shows, visit Theatre in Chicago