EVERYTHING’S FINE,

BUT WHAT IF WE HAD ALSO BEEN AFRAID?

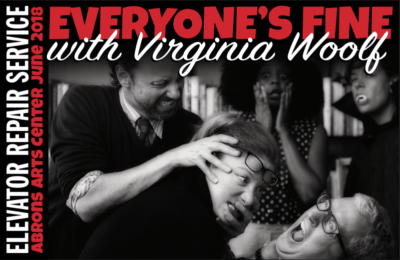

Starting out as a parody of Edward Albee’s Whose Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Kate Scelsa’s Everyone’s Fine with Virginia Woolf is a whimsical and witty feminist attack on what the play views as the failings of male dramatists. An abundance of quips, clever remarks, and innumerable references to drama and contemporary culture make for an engaging enough spectacle, especially for college graduates of a certain type; I confess I felt lost at times amidst all the references and had the thought that maybe if only I had the same mastery of them as the playwright a brilliant world would reveal itself to me.

John Collins’ sharp, fast-paced direction, and the cast’s energetic performances keep the mood lively, the audience laughing, and the time flying. Yet in the end, the play, which Ms. Scelsa wrote specifically for the consistently outstanding Elevator Repair Service, of which she’s been a member for over 15 years, leaves one unmoved.

After a college faculty cocktail party, Martha and George Washington (Annie McNamara and Vin Knight) — she the daughter of the college president, he a tenured professor specializing in Tennessee Williams — have the young professor Nick Sloane (Mike Iveson) and his wife Honey (April Matthis) to their home for a nightcap. What is subtext in Albee Ms. Scelsa states outright. And information about the characters, which in Albee’s drama gets revealed throughout the play, Ms. Scelsa serves up immediately: Martha wants a swap, George killed off their fictional son, Honey is not pregnant, and Nick is there to try and get George to help him get tenure. These are jokes for intellectuals and dilettantes, but they also serve to set the show’s agenda. It’s as if the play is saying: That was the source material, now here’s what we have to say about it.

In Everyone’s Fine, George is gay and Nick mostly gay. Nick was pregnant once, he reveals, but only in fiction. He started writing fan fiction for a fiction community message board, then moved onto slash fiction in which all the fan fiction characters are gay, then to “mpreg,” which is about men having sex with men and getting pregnant. But then the community looked down on his writing as being Mary Sue, which is when one of the gay characters is a disguised version of the author and the fiction is written selfishly for the author’s own pleasure, as opposed to for everyone; this community is all about generosity.

A lot of time is spent on this and other topics which, while perhaps amusing in themselves, offer little in terms of moving the story, exploring characters, or establishing meaningful stakes. George wants to go to bed. Martha wants to be friends with Honey and have sex with Nick. Nick wants tenure. And Honey doesn’t really want anything. Very little if any of this matters as no one sacrifices or struggles to satisfy their desires. But in a way that’s the point.

Everyone’s Fine isn’t intended to be dramatic, it’s intended to be critical, critical of how male writers mistreat basically everyone except men, dramatically speaking. Woody Allen, Tennessee Williams, Ibsen, Albee are mentioned, and the playwright tosses darts at them and others — albeit most likely lovingly — for their various literary misdeeds.

But here Ms. Scelsa runs into two problems. The first is that her critical statements/ observations/insights are, for the most part, not revelatory enough to stand on their own. And second, their presentation isn’t compelling emotionally or intellectually. If  one were to write a play where a character argues a philosophical point it might be useful to have some other character arguing against it so that at the very least the issue can be explored intellectually. And ideally one would also try to create a situation in which that abstract point has real meaningful consequence for the characters.

one were to write a play where a character argues a philosophical point it might be useful to have some other character arguing against it so that at the very least the issue can be explored intellectually. And ideally one would also try to create a situation in which that abstract point has real meaningful consequence for the characters.

A dramatic change occurs at the end of Act II — which Mr. Collins, along with scenic designer Louisa Thompson and lighting designer Ryan Seeling stage quite spectacularly — and a vampire appears. Camilla (Lindsay Hockaday) is her name and instead of blood she feeds on people’s neuroses. Among other things, she is there to explain what this play is about. Here is a partial quote: “’¦when men write about the failures of women, they’re writing about the failure of the vulnerable individual. And when men write about the failures of men, they’re writing about the failure of society.”

Everyone’s Fine isn’t the first place I’ve heard this criticism, and although I personally have a number of issues with it, it does carry weight and is worth exploring. Unfortunately, Ms. Scelsa brings it up as the revelation at the end rather than as a point of departure.

Everyone’s Fine with Virginia Woolf

Elevator Repair Service

Abrons Arts Center Playhouse, 466 Grand St

Wed-Sat at 8; Sat and Sun at 2

ends on June 24, 2018 EXTENDED to June 30

for tickets, call 212.352.3101

or visit Abron Arts or Everyone’s Fine