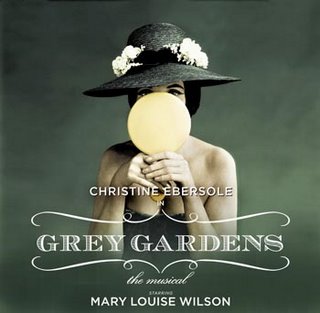

GREYISH GARDENS

The second act of Grey Gardens is a near-perfect little chamber musical. The first act is merely gratuitous. With a nudge here and a shove there, the second act could have been expanded into a wonderful evening in the theater complete unto itself. It is the part of the show that we came to see; the part based on the Maysles Brothers documentary that brought so brilliantly and so terrifyingly to life the existence of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy’s reclusive and eccentric relatives, Edith Bouvier Beale and her daughter “Little” Edie; the part that has inspired the show’s creators to reach such lyrical and comic heights; the part where Christine Ebersole enters the stratosphere and becomes one of the Broadway musical theater’s instant legends, with lustrous support from the spectacular Mary Louise Wilson. It starts with a bang and ends with the most painfully poignant kind of whimper and, on its own, would have sent us out of the theater cheering. Instead, we leave with a vague feeling of having spent a somewhat schizophrenic night out.

Mary Louise Wilson

It’s that first act. True, the second act blots out, to a great degree, the deficiencies of that first act, but it can’t erase it completely. Where the original source material (once again, in that second act) seems to liberate the imaginations of playwright Doug Wright and director Michael Greif, the first act forces them to imagine the past of its two central characters and what may have been the cause of their disorderly lives. All they have come up with are the most tiresome cliché about the life styles of the rich and famous; a cross between The Philadelphia Story and the silly ’˜tennis, anyone?’ kind of musical comedy that went out of style long before The Philadelphia Story. Dad plays golf. Little cousins Jackie and Lee show up for reasons that are obvious but inconsequential. Edith Beale, not terribly happy about her marriage, spends her time with a standard piano-playing gay dissolute who has a way with snappish commentary. Daughter Edie bears less resemblance to the woman she will eventually become than to a typical ingénue of the period. And her beau, the about-to-be war hero Joseph Patrick Kennedy Jr. is reduced to the young, bright, callow and totally disposable leading man to Edie’s ingénue. All of these characters have more flesh on them as ghosts, as they appear in the second act, than they do as real people in the first.

Edith performs for her nieces to her father's dismay

There are bright spots. Scott Frankel’s lively score starts its work early on and Michael Korie’s lyrics do the same. And it would be a shame to lose “Hominy Grits” – the funny parody of “racial” songs – which manages to reflect our delectably innocent musical tastes at the same time that it shames us. And even more missed would be the lovely “Will You?”

Christine Ebersole and cast

And, of course, there is Christine Ebersole, already weaving her magic, finding the steel behind the surface dithering of Edith Beale, the dark corners lurking beneath the sunny surface, the meanness that masks her anguish, revealing traces of what will emerge in full bloom when Ms. Wilson takes over the part in the second act.

Erin Davie as young Little Edie with her intended, Matt Cavenaugh as Joseph Kennedy, Jr

And, ah, that second act! Suddenly, with the force of a hurricane that clears away all the debris it brings with it, all is transformed, and Ms. Ebersole, now playing her own daughter, is there before us singing “The Revolutionary Costume for Today,” a song for which she can claim ownership from this moment on. One can feel the great collective sigh of relief from the audience that precedes the shattering applause that brings the song to an end and allows them to go on any journey the play wants to take them through. This is What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? territory, not really removed entirely from camp, but frighteningly close to an edge of reality that is so fascinating because it is unfamiliar and, yet, all too recognizable. Each song brings with it clarity and insight. There is even a scene, sans music, where mother and daughter talk at and across each other, overlapping each other, reaching a crescendo of not hearing each other, which defines their relationship, followed by a moment of spectacular silence that freezes that relationship in the harsh glare of naked truth.

Mary Louise Wilson and Christine Ebersole

These women, mother and daughter, living in impoverished and decaying splendor, gained notoriety when they were about to be evicted by the actions of their community in East Hampton and who were subsequently saved, just barely, by their most celebrated relative, and by the filmmakers, who, by focusing their cameras on them, gave them both the moment of celebrity they always had the instinct (if not the talent) for. That moment is captured again in this ferociously funny and ultimately moving second act. Once again, the light is on them, and they bask, with professional relish, in that light, as mother, plain and flinty, and daughter, needy and desperate, play out their mutually destructive and self-destructive lives. Ms. Wilson is startlingly subtle as the tougher of the two, and she sings with refreshing directness.

But, just as Ms. Ebersole begins the act with dazzling comic flair, she ends the act, sealing her tragic fate, with her deeply touching interpretation of the haunting “Another Winter in a Summer Town.” Ms. Ebersole not only owns the songs she sings; she may, for this season at least, own the town.

photos by Joan Marcus

Grey Gardens

Walter Kerr Theater, 219 West 48th Street

open run closed July 29, 2007

for tickets, call (212) 239-6200 or visit Telecharge