WHAT A DIFFERENCE A CAST MAKES

Let me tell you a story. A tale of two casts.

Once upon a time there was a playwright whose name was Lillian Hellman. You may have heard of her. She had a taste for melodrama, it’s true, but, at her best, she wrote some of the most effective melodramas in the short history of the American theater. Maybe you’ve heard of The Little Foxes? The Children’s Hour? Watch on the Rhine? Or maybe you know the name because of the three supposedly autobiographical books she wrote in which she romanticized her relationship with a certain mystery writer you may also have heard of. His name was Dashiell Hammett. Or maybe you know her because you saw Jane Fonda play someone named Lillian Hellman in the movie Julia. That’s her. Or, at least, a pretty reasonable facsimile of her. Or, I should say, as she saw herself.

Well, in 1951, Lillian wrote a play called The Autumn Garden which, despite a glittering cast and good reviews and her own reputation for literary brilliance, never really caught on with audiences. Maybe it was the time. Maybe it was the play. Lillian herself said, in an interview with Ward Morehouse, a popular columnist of that time, that it was her favorite play. It might be mentioned in passing that the interview was conducted while imbibing a martini or two. At any rate, it’s the part of the story I happen to like. For one thing, playwrights often say things like “It’s my favorite play” when it’s the one they’ve just finished and they just happen to be plugging. And maybe, or especially, over a dry martini, it’s a little easier to say something you may one day regret saying. The martini is a nice touch because Lillian was said to be the inspiration for the character of Nora Charles, created by Dash (as Hammett was known to his intimates) in The Thin Man, and Nora was famed for being a woman who remained smart despite a martini or two too many. So, in fact, I am not suggesting that the martini colored Lillian’s assessment of her own work. It may even have provided Lillian with the courage to be candid. Something alcohol often does, as Lillian, from first-hand experience, understood.

Well, in 1951, Lillian wrote a play called The Autumn Garden which, despite a glittering cast and good reviews and her own reputation for literary brilliance, never really caught on with audiences. Maybe it was the time. Maybe it was the play. Lillian herself said, in an interview with Ward Morehouse, a popular columnist of that time, that it was her favorite play. It might be mentioned in passing that the interview was conducted while imbibing a martini or two. At any rate, it’s the part of the story I happen to like. For one thing, playwrights often say things like “It’s my favorite play” when it’s the one they’ve just finished and they just happen to be plugging. And maybe, or especially, over a dry martini, it’s a little easier to say something you may one day regret saying. The martini is a nice touch because Lillian was said to be the inspiration for the character of Nora Charles, created by Dash (as Hammett was known to his intimates) in The Thin Man, and Nora was famed for being a woman who remained smart despite a martini or two too many. So, in fact, I am not suggesting that the martini colored Lillian’s assessment of her own work. It may even have provided Lillian with the courage to be candid. Something alcohol often does, as Lillian, from first-hand experience, understood.

It was certainly as different from Lillian’s other plays as could be imagined. It seemed free not only from melodrama, but from politics. It had no plot to speak of and it focused on some people Lillian obviously knew very well, and the problems most of them were having with getting older and having not much to show for what their lives have added up to now that they’ve reached their middle years. It was about a group of people gathered together in one place, at precisely the moment when each of the characters is at the most crucial moment in his or her life, and it was called Chekhovian, because anytime there is a play about a group of people gathered together in one place at precisely the moment when each of the characters is at the most crucial moment in his or her life, it is called Chekhovian. (I will not digress by delivering a lecture on what is Chekhovian and what is not Chekhovian.)

It was certainly as different from Lillian’s other plays as could be imagined. It seemed free not only from melodrama, but from politics. It had no plot to speak of and it focused on some people Lillian obviously knew very well, and the problems most of them were having with getting older and having not much to show for what their lives have added up to now that they’ve reached their middle years. It was about a group of people gathered together in one place, at precisely the moment when each of the characters is at the most crucial moment in his or her life, and it was called Chekhovian, because anytime there is a play about a group of people gathered together in one place at precisely the moment when each of the characters is at the most crucial moment in his or her life, it is called Chekhovian. (I will not digress by delivering a lecture on what is Chekhovian and what is not Chekhovian.)

And, so, to continue the story, I read the play many years ago and, on the page, I was in full agreement with Lillian’s judgment. I became infatuated with the play. And I dreamed of seeing it someday so that I could finally see for myself if the play was as beautiful on stage as it had been on the page. But, alas, revivals come and go, and come again, but The Autumn Garden was rarely if ever revived, and I felt as if I was destined  never to see a fully-staged production of what was one of the works in American dramatic literature I cherished the most. It came to pass that there was a purportedly terrific revival a few years back at the Williamstown Theatre Festival but distance and finances made a trip to Massachusetts impossible at that time. So much for holding to the promise that nothing would stop me from having a dream fulfilled if it was within possibility. Well, it’s also true that, as one gets older, some promises seem less important than others. And less possible. Hadn’t I learned that lesson from Lillian? Isn’t that one of the things she was trying to say in The Autumn Garden?

never to see a fully-staged production of what was one of the works in American dramatic literature I cherished the most. It came to pass that there was a purportedly terrific revival a few years back at the Williamstown Theatre Festival but distance and finances made a trip to Massachusetts impossible at that time. So much for holding to the promise that nothing would stop me from having a dream fulfilled if it was within possibility. Well, it’s also true that, as one gets older, some promises seem less important than others. And less possible. Hadn’t I learned that lesson from Lillian? Isn’t that one of the things she was trying to say in The Autumn Garden?

So, when I heard that The Antaeus Company was planning a revival of The Autumn Garden, I could think of no other theater event in Los Angeles in the past year or so that had me so agog with anticipation. And when I heard it was double cast (as all plays at The Antaeus Company are), I thought that, as an outright fan and as a reviewer with a certain responsibility to live theater, I should definitely see both casts.

This, incidentally, is where the story takes a strange turn, as I suspect some of you might have already guessed (if you are still reading, that is).

The night arrived. I was going to see The Autumn Garden. I took my seat. Tom Buderwitz’s set was so breathtakingly beautiful that I wanted to move in immediately. John Zalewski’s sound design, which sounded like a stampede of tap dancers in a Busby Berkeley film, was odd but intriguing and, in its own tingly way, added to the excitement of being in the theater. The lights came up. The play began.

The night arrived. I was going to see The Autumn Garden. I took my seat. Tom Buderwitz’s set was so breathtakingly beautiful that I wanted to move in immediately. John Zalewski’s sound design, which sounded like a stampede of tap dancers in a Busby Berkeley film, was odd but intriguing and, in its own tingly way, added to the excitement of being in the theater. The lights came up. The play began.

Frankly, my dear, I was not overwhelmed. Here was an ensemble of very good actors, each perfectly cast, saying the lines Lillian wrote, “playing” the play. And yet the play stubbornly refused to come to life. One could hear, every so often, why Lillian was so impressed by her own writing, but, more often than not, one couldn’t help but ponder upon the fact that, perhaps, the audiences in 1951 were right to resist the play, despite the high quality of Lillian’s writing. It was sluggish and aimless. And my only reaction, after three long hours, was “Goodness gracious, am I really going to have to sit through this again? What have I committed myself to?” It wasn’t, let me make absolutely clear, a bad evening of theater. I was truly happy to have finally seen a production of the play.

Frankly, my dear, I was not overwhelmed. Here was an ensemble of very good actors, each perfectly cast, saying the lines Lillian wrote, “playing” the play. And yet the play stubbornly refused to come to life. One could hear, every so often, why Lillian was so impressed by her own writing, but, more often than not, one couldn’t help but ponder upon the fact that, perhaps, the audiences in 1951 were right to resist the play, despite the high quality of Lillian’s writing. It was sluggish and aimless. And my only reaction, after three long hours, was “Goodness gracious, am I really going to have to sit through this again? What have I committed myself to?” It wasn’t, let me make absolutely clear, a bad evening of theater. I was truly happy to have finally seen a production of the play.  And I did feel I was seeing the play. But it cannot be denied that I was disappointed that it did not live up to the experience of reading it. Its biggest problem was that, instead of proving ahead of its time, it seemed very much a period piece. Its costumes, for one, looked as if they had come off the rack of a vintage clothing store and the actors looked, for the most part, uncomfortable in them. And its subject matter seemed not only dated but overly familiar, as if so many plays written since then have said the same things and said them better, with more depth and acuity. And by not doing it in three acts, as intended – but instead bringing the first act down after the first scene of

And I did feel I was seeing the play. But it cannot be denied that I was disappointed that it did not live up to the experience of reading it. Its biggest problem was that, instead of proving ahead of its time, it seemed very much a period piece. Its costumes, for one, looked as if they had come off the rack of a vintage clothing store and the actors looked, for the most part, uncomfortable in them. And its subject matter seemed not only dated but overly familiar, as if so many plays written since then have said the same things and said them better, with more depth and acuity. And by not doing it in three acts, as intended – but instead bringing the first act down after the first scene of  the second act – made the evening seem even longer than it might have seemed with a second intermission. And one had time to notice that the beauties of the set design were diminished by a pesky curtain, which presumably led to the front door of the house, from which actors were forced to make the clumsiest of entrances and exits.

the second act – made the evening seem even longer than it might have seemed with a second intermission. And one had time to notice that the beauties of the set design were diminished by a pesky curtain, which presumably led to the front door of the house, from which actors were forced to make the clumsiest of entrances and exits.

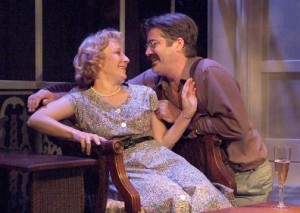

Oddly enough, despite my disappointment, I came home and re-read the play yet one more time, and I actually found myself curious again to see the second cast. “What, after all,” I said to myself, “can I do?” It seemed, when push came to shove, the least I could do. And here is where that strange turn took place.  The very next night, within minutes after the lights came up, instead of sitting there and watching the play, I was drawn into it. It was as if this ensemble had woven a magical web over the audience and taken them inside the lives of Lillian’s people. Suddenly, these characters were so human, so in contact with each other, it was as if they not only really knew each other for years, but also knew every inch of the house they shared. And so what was said about them seemed fresh and revealing rather than tired and stale. Intermission came at exactly the right moment. It was, all of it, perched somewhere between comedy and heartbreak so that, beneath Lillian’s withering gaze, and

The very next night, within minutes after the lights came up, instead of sitting there and watching the play, I was drawn into it. It was as if this ensemble had woven a magical web over the audience and taken them inside the lives of Lillian’s people. Suddenly, these characters were so human, so in contact with each other, it was as if they not only really knew each other for years, but also knew every inch of the house they shared. And so what was said about them seemed fresh and revealing rather than tired and stale. Intermission came at exactly the right moment. It was, all of it, perched somewhere between comedy and heartbreak so that, beneath Lillian’s withering gaze, and  her almost mean-spirited effort to make everyone see the truth, there was genuine compassion and an emotional and intellectual certainty to every revelation. And, because it was so true, so pure, so fluid, the actors even brought out, through the not-so-simple art of characterization, the sheer gracefulness of Lillian’s writing. This was not only the play I read and adored; it was a brand-new confrontation with the play. It was everything a revival should be. And it seemed to flow right by, even though it ran every bit as long as it had the first night. Ah, the mysteries of the theater!

her almost mean-spirited effort to make everyone see the truth, there was genuine compassion and an emotional and intellectual certainty to every revelation. And, because it was so true, so pure, so fluid, the actors even brought out, through the not-so-simple art of characterization, the sheer gracefulness of Lillian’s writing. This was not only the play I read and adored; it was a brand-new confrontation with the play. It was everything a revival should be. And it seemed to flow right by, even though it ran every bit as long as it had the first night. Ah, the mysteries of the theater!

Not every story has a moral, but this one does. And it is this: you can do the same play, in the same theater, on the same set, with the same director (Larry Biederman, in this particular instance), and not necessarily provide the same experience. It is a testament to the art of acting – and specifically the art of ensemble acting – that such a vast difference is not only conceivable but altogether possible. And so, if I were to recommend The Autumn Garden, I would do so by telling the reader to see the cast called “Idealists” rather than the cast called “Dreamers.” The “Dreamers” may, in time, find their own way through to the play’s rhythms, but, at the moment, the “Idealists” win, hands down. But, for other actors, seeing both casts would be a valuable object lesson in observing just exactly what a great difference different actors can make.

Not every story has a moral, but this one does. And it is this: you can do the same play, in the same theater, on the same set, with the same director (Larry Biederman, in this particular instance), and not necessarily provide the same experience. It is a testament to the art of acting – and specifically the art of ensemble acting – that such a vast difference is not only conceivable but altogether possible. And so, if I were to recommend The Autumn Garden, I would do so by telling the reader to see the cast called “Idealists” rather than the cast called “Dreamers.” The “Dreamers” may, in time, find their own way through to the play’s rhythms, but, at the moment, the “Idealists” win, hands down. But, for other actors, seeing both casts would be a valuable object lesson in observing just exactly what a great difference different actors can make.

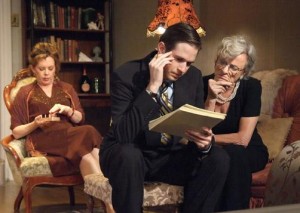

The “Idealists” – Faye Grant, Anne Gee Byrd, James Sutorius, Stoney Westmoreland, Joe Delafield, Jeanie Hackett, Zoe Perry, Lily Knight, Stephen Caffrey, Jane Kaczmarek, Saundra McClain, Reba Waters – are extraordinary, but I will especially remember Ms. Byrd’s no-nonsense matriarch; the exquisitely wrought scenes between Sutorius and Ms. Grant; the way Ms. Kaczmarek can project happiness and sorrow and boredom and curiosity and vulnerability and strength and wisdom all in the same moment; the dazzling drunk scene in which Caffrey pulls out all the stops without losing his humanity; the way the magnificent Zoe Perry creeps into our heart and then shatters us with

The “Idealists” – Faye Grant, Anne Gee Byrd, James Sutorius, Stoney Westmoreland, Joe Delafield, Jeanie Hackett, Zoe Perry, Lily Knight, Stephen Caffrey, Jane Kaczmarek, Saundra McClain, Reba Waters – are extraordinary, but I will especially remember Ms. Byrd’s no-nonsense matriarch; the exquisitely wrought scenes between Sutorius and Ms. Grant; the way Ms. Kaczmarek can project happiness and sorrow and boredom and curiosity and vulnerability and strength and wisdom all in the same moment; the dazzling drunk scene in which Caffrey pulls out all the stops without losing his humanity; the way the magnificent Zoe Perry creeps into our heart and then shatters us with  her European pragmatism in the midst of all these deceptive and self-deceiving Americans; the lovely interplay between Westmoreland and Ms. Knight which includes one of the best closing lines in any American play when his character says “I’ve never liked liars – least of all those who lie to themselves” and her character responds by saying,”Never mind. Most of us lie to ourselves, darling, most of us.” And I should add that if you see the “Idealists” and Ms. Byrd or Sutorius or Westmoreland or Ms. Perry should be, for some reason, “indisposed,” the substitutions of Dawn Didawick or Kurtwood Smith or Josh Clark or Jeanne Syquia in their parts would not be, in any way, harmful to the fabric of the

her European pragmatism in the midst of all these deceptive and self-deceiving Americans; the lovely interplay between Westmoreland and Ms. Knight which includes one of the best closing lines in any American play when his character says “I’ve never liked liars – least of all those who lie to themselves” and her character responds by saying,”Never mind. Most of us lie to ourselves, darling, most of us.” And I should add that if you see the “Idealists” and Ms. Byrd or Sutorius or Westmoreland or Ms. Perry should be, for some reason, “indisposed,” the substitutions of Dawn Didawick or Kurtwood Smith or Josh Clark or Jeanne Syquia in their parts would not be, in any way, harmful to the fabric of the  whole. I was particularly fascinated by how differently Ms. Byrd and Ms. Didawick play the same role and how strikingly good each one is, but that Ms. Byrd is luckier to be in the cast that more elegantly proves the rightness of reviving the play that our friend Lillian justifiably declared was her favorite: a genuinely neglected masterpiece she dedicated with love to Dash – The Autumn Garden.

whole. I was particularly fascinated by how differently Ms. Byrd and Ms. Didawick play the same role and how strikingly good each one is, but that Ms. Byrd is luckier to be in the cast that more elegantly proves the rightness of reviving the play that our friend Lillian justifiably declared was her favorite: a genuinely neglected masterpiece she dedicated with love to Dash – The Autumn Garden.

harveyperr @ stageandcinema.com

photos by Ed Krieger

scheduled to close December 19 at time of publication

for tickets, visit http://www.antaeus.org/2010season.html