MORE GOOD L.A. THEATER AROUND THAN ONE IMAGINES

There is so much theater activity in Los Angeles that there is bound to be a lot of good theater. But I have been so burned out by the extraordinary amount of bad theater I’ve had to sit through that I’ve seriously considered taking a vacation from reviewing. There has been entirely too much actor-driven work, in which the actors seem less interested in playing the play than in auditioning for television. I have grown impatient with most of the local reviewers who insist on pimping for Los Angeles theater even when it is not so good, in order to keep the theater thriving and alive, when, in fact, that sort of criticism does more harm than good in the long run. Too many theater companies get a free pass; nobody should expect any company to hit a home run every time they are up at bat. And the big theaters seem to look everywhere but their own home town for the work they produce – say what you will about Gordon Davidson, he was genuinely interested in developing new playwrights – and something has been irretrievably lost in the process. What ever happened to New Theater For Now, for example? And why did we let UCLALive fall by the wayside?

So why does it suddenly feel, amidst a sudden spurt of real honest-to-goodness desperation to do the right thing, as if Los Angeles may actually become a true theater town after all? This may be a passing thing – a fountain of possibilities in an otherwise theatrical desert – but it needs to be paid attention to. Something exciting is going on. Mind you, it isn’t all the paradise some of us may have been waiting for, but, for now, it is more than good enough.

—

Take La Razón Blindada (Armored Reason) which, fortunately, has been extended to December 11 (it’s been running a long while, and I declare a Mea Culpa in not getting to see it sooner); this is a dazzling achievement. Attempting to create a Spanish-language theater that is dedicated to the intellectual potential of its targeted audience – and providing subtitles to include an English-speaking audience – is, in itself, admirable enough, but the work produced is as staggering in its execution as it is praiseworthy in its intentions. In the 1980s, the Argentine dictatorship placed its artists and dissidents into prisons and AristÃdes Vargas, who wrote and directed the play, has imagined what it would be like if the prisoners and their visitors (who came every Sunday) engaged in story-telling to pass their time together.

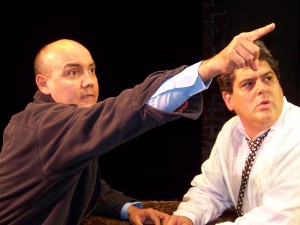

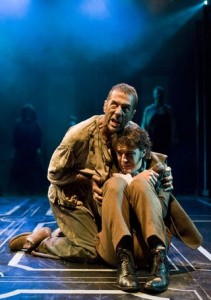

Take La Razón Blindada (Armored Reason) which, fortunately, has been extended to December 11 (it’s been running a long while, and I declare a Mea Culpa in not getting to see it sooner); this is a dazzling achievement. Attempting to create a Spanish-language theater that is dedicated to the intellectual potential of its targeted audience – and providing subtitles to include an English-speaking audience – is, in itself, admirable enough, but the work produced is as staggering in its execution as it is praiseworthy in its intentions. In the 1980s, the Argentine dictatorship placed its artists and dissidents into prisons and AristÃdes Vargas, who wrote and directed the play, has imagined what it would be like if the prisoners and their visitors (who came every Sunday) engaged in story-telling to pass their time together.  The stories they tell are, in effect, the picaresque saga of Cervantes’s Don Quixote and Sancho Panza as filtered through a Kafkaesque prism, with the prisoner becoming the man of La Mancha and his visitor becoming Panza who, in turn, takes on the personae of many other characters including literature’s most famous horse, Rosinante. What is truly remarkable is how vibrantly reflexive the actors – Jesús Castaños-Chima and Tony Duran – are, as they travel through the world Vargas has not merely staged but has ingeniously choreographed. The subtitles are dense, but, if they detract from watching the actors, I suggest concentrating on the actors, for their body language is truly universal and, in the best sense, extravagantly theatrical.

The stories they tell are, in effect, the picaresque saga of Cervantes’s Don Quixote and Sancho Panza as filtered through a Kafkaesque prism, with the prisoner becoming the man of La Mancha and his visitor becoming Panza who, in turn, takes on the personae of many other characters including literature’s most famous horse, Rosinante. What is truly remarkable is how vibrantly reflexive the actors – Jesús Castaños-Chima and Tony Duran – are, as they travel through the world Vargas has not merely staged but has ingeniously choreographed. The subtitles are dense, but, if they detract from watching the actors, I suggest concentrating on the actors, for their body language is truly universal and, in the best sense, extravagantly theatrical.

—

Next take The Little Flower Of East Orange, which marks the first collaboration of the Elephant Theatre Company and New York’s LAByrinth Theater Company – one that, if its first production is an example, is going to be a fruitful one – and Stephen Adly Guirgis’s play is receiving the kind of

Next take The Little Flower Of East Orange, which marks the first collaboration of the Elephant Theatre Company and New York’s LAByrinth Theater Company – one that, if its first production is an example, is going to be a fruitful one – and Stephen Adly Guirgis’s play is receiving the kind of  production that, quite simply, makes one want to stand up and cheer. The play, like most great American plays, is about family ties, about mothers and sons, mothers and daughters, and about the often horrific, often tender things that such relationships are built on and are destroyed by. Therese Marie (a luminous and touching Melanie

production that, quite simply, makes one want to stand up and cheer. The play, like most great American plays, is about family ties, about mothers and sons, mothers and daughters, and about the often horrific, often tender things that such relationships are built on and are destroyed by. Therese Marie (a luminous and touching Melanie  Jones) would rather kill herself than be a burden on her children, which of course has the totally opposite effect. Her son Danny (the splendid Michael Friedman who is East Orange, New Jersey not only in the authenticity of his accent but straight down to his bones) is a drug addict. Her daughter Justina (the hard-edged Marisa O’Brien, whose opening

Jones) would rather kill herself than be a burden on her children, which of course has the totally opposite effect. Her son Danny (the splendid Michael Friedman who is East Orange, New Jersey not only in the authenticity of his accent but straight down to his bones) is a drug addict. Her daughter Justina (the hard-edged Marisa O’Brien, whose opening  monologue brilliantly and hilariously elucidates the degree to which Guirgis is willing to explore the boundaries of style) is a tough and uncompromisingly pragmatic tyrant. Therese Marie’s memories haunt her, particularly the memory of her abusive deaf father (Timothy McNeil in a brave and devastating performance), which

monologue brilliantly and hilariously elucidates the degree to which Guirgis is willing to explore the boundaries of style) is a tough and uncompromisingly pragmatic tyrant. Therese Marie’s memories haunt her, particularly the memory of her abusive deaf father (Timothy McNeil in a brave and devastating performance), which  defines what Guirgis is trying to tell us about parents and children and the ambivalence which turns truth into bromide, anger into love of a sort. Guirgis fills the play with a rich assortment of vividly drawn characters, including a no-nonsense and oddly sympathetic male nurse (the strong and funny Alejandro Furth) and Danny’s strung-out girlfriend (a

defines what Guirgis is trying to tell us about parents and children and the ambivalence which turns truth into bromide, anger into love of a sort. Guirgis fills the play with a rich assortment of vividly drawn characters, including a no-nonsense and oddly sympathetic male nurse (the strong and funny Alejandro Furth) and Danny’s strung-out girlfriend (a  mesmerizing Kate Huffman) among others (all of them quite good). David Fofi provides pitch-perfect direction. This is work of genuine commitment and passion. A slight quibble: the contours of the stage of the Lillian Theatre are almost too expansive for the heated intensity of the play and Joel Daavid’s set, while workable, doesn’t completely solve the problem. But here, the play’s very much the thing.

mesmerizing Kate Huffman) among others (all of them quite good). David Fofi provides pitch-perfect direction. This is work of genuine commitment and passion. A slight quibble: the contours of the stage of the Lillian Theatre are almost too expansive for the heated intensity of the play and Joel Daavid’s set, while workable, doesn’t completely solve the problem. But here, the play’s very much the thing.

—

And then there’s the Rogue Machine Theatre’s taut and muscular production of Cormac McCarthy’s The Sunset Limited. This is not so much a play as it is an extended argument, but it is the liveliest, drollest and most furiously passionate argument you are likely to hear in any theater anywhere. White, an intellectual whose vision of the world is so despairing that he can never give up on giving up, tries to kill himself, but is saved by Black, a sympathetic ex-con whose belief in God, he is convinced, can get White – and, by extension, all of us – through his severe depression if White would only acknowledge some divine presence. Black literally keeps White a prisoner until he can no longer, in

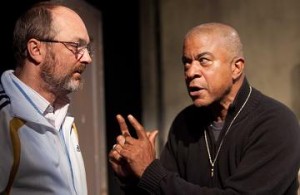

And then there’s the Rogue Machine Theatre’s taut and muscular production of Cormac McCarthy’s The Sunset Limited. This is not so much a play as it is an extended argument, but it is the liveliest, drollest and most furiously passionate argument you are likely to hear in any theater anywhere. White, an intellectual whose vision of the world is so despairing that he can never give up on giving up, tries to kill himself, but is saved by Black, a sympathetic ex-con whose belief in God, he is convinced, can get White – and, by extension, all of us – through his severe depression if White would only acknowledge some divine presence. Black literally keeps White a prisoner until he can no longer, in  good conscience, continue to do so. You might not think a debate of this nature could keep you on the edge of your seat, but you’d be wrong. It is partly due to the transcendent quality of McCarthy’s mordant writing, but is, above all, due to the impeccably detailed direction of John Perrin Flynn and the superb performances he elicits from Ron Bottita, whose quiet resignation hides the seething and roiling emotions waiting to erupt in White, and from Tucker Smallwood who, as Black, seems to have a light inside him that radiates with such power that his tough exterior seems always on the verge of being shattered. Smallwood’s portrait of a man of faith is the

good conscience, continue to do so. You might not think a debate of this nature could keep you on the edge of your seat, but you’d be wrong. It is partly due to the transcendent quality of McCarthy’s mordant writing, but is, above all, due to the impeccably detailed direction of John Perrin Flynn and the superb performances he elicits from Ron Bottita, whose quiet resignation hides the seething and roiling emotions waiting to erupt in White, and from Tucker Smallwood who, as Black, seems to have a light inside him that radiates with such power that his tough exterior seems always on the verge of being shattered. Smallwood’s portrait of a man of faith is the  most beautiful expression of that faith that I have seen since the great Ethel Waters, whose faith informed almost everything she did in a most triumphant way, walked this planet. That White resists Black is a testament to the fury of his despondent vision. And the last image, with help from Dan Weingarten’s poetic lighting, will burn into your memory. The Sunset Limited must be experienced.

most beautiful expression of that faith that I have seen since the great Ethel Waters, whose faith informed almost everything she did in a most triumphant way, walked this planet. That White resists Black is a testament to the fury of his despondent vision. And the last image, with help from Dan Weingarten’s poetic lighting, will burn into your memory. The Sunset Limited must be experienced.

—

Although I will never understand why A Noise Within decided to use Neil Bartlett’s Classics Illustrated adaptation of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations, which is not merely a vulgar reduction of this great novel but one that fails to capture the very qualities that make the novel great, I must admit that, as imaginatively directed by Geoff Elliott and Julia Rodriguez-Elliott, the production is a marvel of stagecraft and the ensemble is, for the most part, skillfully adroit. Now, it may be impossible to get all of Great Expectations down to two hours, but there exists a film version, directed by David Lean at his very best, that managed at least to get at its spirit and at something of its essence. The first act is smooth enough, even with

Although I will never understand why A Noise Within decided to use Neil Bartlett’s Classics Illustrated adaptation of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations, which is not merely a vulgar reduction of this great novel but one that fails to capture the very qualities that make the novel great, I must admit that, as imaginatively directed by Geoff Elliott and Julia Rodriguez-Elliott, the production is a marvel of stagecraft and the ensemble is, for the most part, skillfully adroit. Now, it may be impossible to get all of Great Expectations down to two hours, but there exists a film version, directed by David Lean at his very best, that managed at least to get at its spirit and at something of its essence. The first act is smooth enough, even with  deficiencies, and moves sometimes thrillingly through the setting up of the story, though the shrillness of Joe Gargery’s wife made me long for her death, which, sad to say, did not come soon enough. It’s the hurried second act where the trouble lies. The unbearably touching and grandly sentimental death of Magwitch, Pip’s saviour, is treated as a footnote. And the death of Miss Havisham goes by practically without notice. Still, as I said, the whole venture moves swiftly and in all sorts of inventive ways, and, even when it doesn’t entirely make sense, it has a tingle to it. And Jaimi Paige as Estella took my breath away – she wasn’t acting; she was Estella come to life.

deficiencies, and moves sometimes thrillingly through the setting up of the story, though the shrillness of Joe Gargery’s wife made me long for her death, which, sad to say, did not come soon enough. It’s the hurried second act where the trouble lies. The unbearably touching and grandly sentimental death of Magwitch, Pip’s saviour, is treated as a footnote. And the death of Miss Havisham goes by practically without notice. Still, as I said, the whole venture moves swiftly and in all sorts of inventive ways, and, even when it doesn’t entirely make sense, it has a tingle to it. And Jaimi Paige as Estella took my breath away – she wasn’t acting; she was Estella come to life.

—

It may be to my advantage that I never saw Stomp because I am still under the spell of The Lost and Found Orchestra, the nimble group of musicians who perform with such amazing skill in Pandemonium, a show that is apparently patterned on Stomp. I don’t really know what to say about this, or why theater reviewers should even consider reviewing it, because, as I thought, at first, it isn’t really theater. But, upon consideration, I thought again and realized that it not only is theater but may very well be the theater of the future. Surely, producers, who don’t really know what a young audience wants but who are notoriously trying to cash in with what will be the next hip-hop musical hit, would be better off looking at a show like Pandemonium for inspiration than a show like

It may be to my advantage that I never saw Stomp because I am still under the spell of The Lost and Found Orchestra, the nimble group of musicians who perform with such amazing skill in Pandemonium, a show that is apparently patterned on Stomp. I don’t really know what to say about this, or why theater reviewers should even consider reviewing it, because, as I thought, at first, it isn’t really theater. But, upon consideration, I thought again and realized that it not only is theater but may very well be the theater of the future. Surely, producers, who don’t really know what a young audience wants but who are notoriously trying to cash in with what will be the next hip-hop musical hit, would be better off looking at a show like Pandemonium for inspiration than a show like  Rent or In the Heights. What transpires is a series of abstract sketches in which musicians play all these delightfully toy-like instruments, from prettily designed upright bass cases to orange traffic cones to saws, while creating images that have a rather nicely haunting visual effect. The performers seem casual enough, but they are as precise as the Rockettes; their main attribute is that they are also as playful as otters. One gets the feeling they would be fun to hang with. Lovely as it is, it does get a bit tiresome and some of the clowning could be curtailed somewhat, and, in the second half of the evening, this show, that could play both in Budapest and Las Vegas with equal ease, seems to begin anticipating the Vegas gig.

Rent or In the Heights. What transpires is a series of abstract sketches in which musicians play all these delightfully toy-like instruments, from prettily designed upright bass cases to orange traffic cones to saws, while creating images that have a rather nicely haunting visual effect. The performers seem casual enough, but they are as precise as the Rockettes; their main attribute is that they are also as playful as otters. One gets the feeling they would be fun to hang with. Lovely as it is, it does get a bit tiresome and some of the clowning could be curtailed somewhat, and, in the second half of the evening, this show, that could play both in Budapest and Las Vegas with equal ease, seems to begin anticipating the Vegas gig.

—

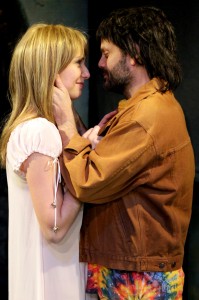

Finally, in the best play in town, Rock’n’Roll, Tom Stoppard – perhaps the last of the great language-conscious playwrights – has written his most humane and personal play since his written-for-television An Englishman Abroad, and one that will stir the passions of anyone who ever considered idealistically the possibilities of Communism until they were rudely awakened by the discovery of how Stalinism brutally destroyed that idealism. It was exacerbated by the shock of the Eastern European countries rising in revolt against Stalin’s tyranny. It marked the end of an era which, to some, was heartbreak of the most profound kind. Set between the Prague Spring and the Velvet Revolution, Jan, born Czech, leaves his beloved Cambridge, where he was mentored by Max, his Marxist professor, to return

Finally, in the best play in town, Rock’n’Roll, Tom Stoppard – perhaps the last of the great language-conscious playwrights – has written his most humane and personal play since his written-for-television An Englishman Abroad, and one that will stir the passions of anyone who ever considered idealistically the possibilities of Communism until they were rudely awakened by the discovery of how Stalinism brutally destroyed that idealism. It was exacerbated by the shock of the Eastern European countries rising in revolt against Stalin’s tyranny. It marked the end of an era which, to some, was heartbreak of the most profound kind. Set between the Prague Spring and the Velvet Revolution, Jan, born Czech, leaves his beloved Cambridge, where he was mentored by Max, his Marxist professor, to return  to Czechoslovakia and a life that he soon discovers is not only repressive but violently opposed to the music that he loves. When he returns to England, Max is sadder but not wiser or perhaps still unflappably holding onto his utopian dream, and Jan’s efforts to save Max, through some hard-line truths, are rebuffed by his mentor. The impasse they reach is complicated and complex. But – and this play was dedicated to Vaclav Havel – despite the confusions these historical changes created, the play tries to reconcile the confusions by at least paying tribute to the rock and roll which ultimately and heart-stirringly triumphs over politics. The first time I saw this play, on the Broadway stage, I identified so thoroughly with its very emotional connections and its intellectual challenges that I left the theater bathed in tears, tears of sadness and tears of joy. How I wish everyone could have seen that transcendent production.

to Czechoslovakia and a life that he soon discovers is not only repressive but violently opposed to the music that he loves. When he returns to England, Max is sadder but not wiser or perhaps still unflappably holding onto his utopian dream, and Jan’s efforts to save Max, through some hard-line truths, are rebuffed by his mentor. The impasse they reach is complicated and complex. But – and this play was dedicated to Vaclav Havel – despite the confusions these historical changes created, the play tries to reconcile the confusions by at least paying tribute to the rock and roll which ultimately and heart-stirringly triumphs over politics. The first time I saw this play, on the Broadway stage, I identified so thoroughly with its very emotional connections and its intellectual challenges that I left the theater bathed in tears, tears of sadness and tears of joy. How I wish everyone could have seen that transcendent production.

Alas, in Barbara Schofield’s by-the-numbers production, polemics take precedence over humanity. The first act is impossibly stiff and cold. The decision to have the Czech characters speak with accents when they are speaking with the English and in their own voices when they are speaking Czech to each other is what Stoppard asks for, but

Alas, in Barbara Schofield’s by-the-numbers production, polemics take precedence over humanity. The first act is impossibly stiff and cold. The decision to have the Czech characters speak with accents when they are speaking with the English and in their own voices when they are speaking Czech to each other is what Stoppard asks for, but  somehow the flatness of the American voices not only does serious damage to the cadences of Stoppard’s rhythmic language, but proves confusing and ultimately weakens Benjamin Burdick’s valiant, sympathetic and insightful approach to the part. And Will Kepper, who bears a remarkable resemblance to Lenin in profile and which is probably why he was cast in the part, turns Max into a one-note, slightly bombastic figure, never

somehow the flatness of the American voices not only does serious damage to the cadences of Stoppard’s rhythmic language, but proves confusing and ultimately weakens Benjamin Burdick’s valiant, sympathetic and insightful approach to the part. And Will Kepper, who bears a remarkable resemblance to Lenin in profile and which is probably why he was cast in the part, turns Max into a one-note, slightly bombastic figure, never  evoking the empathy Stoppard has for the character. The second act is buoyed by the presence of three excellent actors – Maxie Solters as Jan’s childhood flame, Amanda Weir as her daughter, Rona Nix as the pleasantly arrogant wife of a Thatcherite – and by its final moments, which are clearly fool-proof because, once again, it was hard to hold back one’s tears. So, while it is good to have such an important and beautiful play in our midst, this Rock’n’Roll neither rocks nor rolls. But nothing can really put out the flame burning in Stoppard’s heart.

evoking the empathy Stoppard has for the character. The second act is buoyed by the presence of three excellent actors – Maxie Solters as Jan’s childhood flame, Amanda Weir as her daughter, Rona Nix as the pleasantly arrogant wife of a Thatcherite – and by its final moments, which are clearly fool-proof because, once again, it was hard to hold back one’s tears. So, while it is good to have such an important and beautiful play in our midst, this Rock’n’Roll neither rocks nor rolls. But nothing can really put out the flame burning in Stoppard’s heart.

harveyperr @ stageandcinema.com

La Razón Blindada

photos by Jay McAdams

extended to December 11 at time of publication

for tickets, visit http://www.24thstreet.org/productions/la-razon-blindada

The Little Flower Of East Orange

photos by Joel Daavid

scheduled to close December 18 at time of publication

for tickets, visit http://www.elephanttheatrecompany.com

The Sunset Limited

photos by John P. Flynn

scheduled to close December 19 at time of publication (check for extensions)

for tickets, visit http://roguemachinetheatre.com/

Great Expectations

scheduled to close December 19 at time of publication

for tickets, visit http://anoisewithin.org/theplays.html

Pandemonium played at UCLA’s Royce Hall November 16-18

for tickets to future performances around the country and beyond, visit http://www.pandemoniumtheshow.com/

Rock’n’Roll

photos by Tom Burruss

scheduled to close December 18 at time of publication

for tickets, visit http://www.openfist.org