THE TRUTH – IN BLACKFACE

The sheer exuberant energy of one of the most formidably talented casts on Broadway rushing down aisles and onto the stage of The Lyceum is enough to knock any theatergoer out of his post-dinner lethargy and into head-bobbing, knee-pumping involvement. Once again the unconventional Kander and Ebb (Kiss of the Spider Woman, Chicago, Cabaret) have gleefully (and skillfully) dismantled expectations of a production with social conscience like a four-year-old boy stomping though his own meticulously constructed city of building blocks.

Using the format of a minstrel show to mitigate the horrific history of The Scottsboro Boys is courageous and subversively persuasive. How else could a multi-cultural audience sit through lyrics like “Glory be to our electric chair’¦it’s not every boy gets to light up the sky” and “Let me tell you honey, there’s nothing like Jew money” — the latter term actually used by the Alabama Attorney General trying the  original case? Remember the scathing “If You Could See Her Through My Eyes” from Cabaret? How, unless in the guise of full-out vaudeville, could an audience watch black actors in blackface, playing whites (even playing white women!)? Pushing the envelope seems a woefully inadequate term.

original case? Remember the scathing “If You Could See Her Through My Eyes” from Cabaret? How, unless in the guise of full-out vaudeville, could an audience watch black actors in blackface, playing whites (even playing white women!)? Pushing the envelope seems a woefully inadequate term.

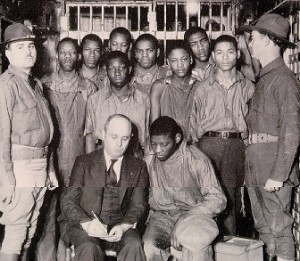

In 1931, nine innocent African American boys – strangers to each other except for two brothers – were pulled off a freight train when two “Alabama ladies” accused them of rape to deflect from their own illegal hitchhiking. Despite evidence and subsequent testimony, they were imprisoned, found guilty at a quick sham trail, and all except the twelve year old were sentenced to death for rape.

Word traveled north. A reprieve came from the Supreme Court, who felt the defendants were not adequately represented. Literally decades of trials followed. The boys became a cause célèbre. One can imagine the harrowing time spent in manual labor, mistreatment and solitary. “We need everyone’s names. We need to know  where to send the bodies,” sneers a guard. Looking out the cell window, one prisoner sees a lynch mob gathering. A boy is selling wooden figures of hanged black men from a tree branch. His name is George Wallace.

where to send the bodies,” sneers a guard. Looking out the cell window, one prisoner sees a lynch mob gathering. A boy is selling wooden figures of hanged black men from a tree branch. His name is George Wallace.

Minstrel shows were endemic to 19th Century America, even considered mainstream. Representing every shameful misconception about blacks, the context drives home the disgrace of the times. We get the message clearly, and fortunately, it’s never heavy-handed, but accomplished high-low humor. (Interesting, four of the paroled Scottsboro Boys actually appeared in vaudeville.)

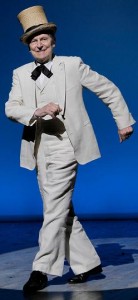

On stage, the judicial fiasco is helmed by John Cullum as The Interlocutor, the play’s single white face, effectively representing the sins of all bigoted whites. Watching him personify stentorian justice (read: prejudice) while standing on a chair in fifteen foot robes or trying to lead the boys in a cakewalk as they scrape off their shoe polish make-up, one can only admire his spirited longevity. Aptly cast, Cullum is just slowed down enough to play The Past. The twinkle in his eye has not diminished.

Employing the embarrassing Uncle Tom buffoonery of Mr. Tambo (Forest McClendon) and Mr. Bones (Colman Domingo) couldn’t make its derogatory cartoon aspect clearer. Domingo and McClendon are sparkplugs — whether playing music hall lawyers, cinematically sadistic prison guards, or trussed up as the so-called victims. When the actors questioned their exaggerated portrayals, Kander encouraged them to just “go.” And so they do — with craft, zeal, humor, and imagination. These are thespians of the highest order.

As Haywood Patterson, Joshua Henry creates a substantial Robeson-like theatrical presence. His voice is deep, clear and resonant. A beautifully calibrated, naturalistic performance has us cringe when he timidly shucks his way through a verse or two. Henry’s anger and frustration is visceral. His attempted escape is like watching dance.

As Haywood Patterson, Joshua Henry creates a substantial Robeson-like theatrical presence. His voice is deep, clear and resonant. A beautifully calibrated, naturalistic performance has us cringe when he timidly shucks his way through a verse or two. Henry’s anger and frustration is visceral. His attempted escape is like watching dance.

Every member of the cast deserves mention. They sing, dance, strut, act, and mug well, never dropping energy or losing focus for a moment.

Susan Stroman has done a terrific job with challenging material. Her choreography is robust. The style and culture of the minstrel tradition winds through the piece seamlessly. Dramatic devices, like an integrated shadow play and the extremely innovative repeated reconstruction of her “set,” are surprising and inventive. Stroman uses the whole stage like a canvas in the hands of a master. Whether real or grotesque, characters are defined.

Beowulf Boritt’s simple set — literally a pile of chairs — becomes whatever’s needed with alacrity and cleverness. Toni-Leslie James costumes cross the line between appropriate and being noteworthy for their clownish originality. David Loud’s Music Direction and Vocal Arrangements meld genres to their best advantage. The sound is engaging and appealing.

Bookwriter David Thompson has made fluent that which might easily have been lurching, accessible what might otherwise have been unacceptable. He never loses the truth — or its effect — while entertaining.

The bankably talented team of Kander & Ebb has pulled another rabbit out of the hat. Controversy is good for theater. The show does what it sets out to do. Clear context and intention keep otherwise offensive material from overwhelming the audience. The Scottsboro Boys is an antic shindig with a dark heart’¦unique and powerful — an eruption of entertainment.

photos by Paul Kolnik

The Scottsboro Boys

Lyceum Theatre, 149 W. 45th St.

ended on December 12, 2010 (49 performances)

for more info, visit Scottsboro Musical