STORIES BY AND FOR THE HEART

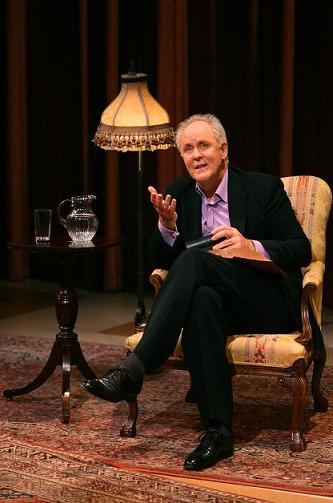

At the start of the second half of Stories By Heart, John Lithgow tells us that, originally, the first half was all there was; but his audience, like children, having heard one story, wanted “more.” In this instance, more proves to be less.

If I had left at intermission, I would have been shouting from my rooftop that everyone should make sure that, if they see nothing else, they should see Stories By Heart and get a glorious immersion into the art of storytelling. And see it done by an absolute master of the form. Lithgow is so gently persuasive and so deceptively simple at telling us tales of his childhood that we are drawn into his magical web of words and feelings as if he had indeed entered our own idealized childhoods. We have all been read to by our parents and it is most probable that the memories of those bedtime experiences defined for us the very moment when we learned to fall in love with literature and, even more, with language. When he takes out the book – he says and we believe him that it is the same book from which his father read to him – to start reading, there is the alluring comfort of being read to again. But, within moments, Lithgow puts the book aside and tells, by heart, the fantastically witty and often downright hilarious short story by the great P.G. Wodehouse, “Uncle Fred Flits By.”

But Lithgow doesn’t just tell the story; he becomes each and every character and, with just a look here, a gesture there, makes each distinct from the other, and he has such a rollicking time doing it that it’s impossible not to savor with utter delight how much fun we’ve been missing not having been read to in all the years that have passed since the last time we were read to. Heady experience, that. And Wodehouse fits Lithgow’s reading skills so perfectly, it’s as if they were one. And, indeed, when a writer’s words get into you and then start coming out of you, that is exactly what should happen. Of course, having heard Lithgow read that story so brilliantly, one wants “more.”

But Lithgow doesn’t just tell the story; he becomes each and every character and, with just a look here, a gesture there, makes each distinct from the other, and he has such a rollicking time doing it that it’s impossible not to savor with utter delight how much fun we’ve been missing not having been read to in all the years that have passed since the last time we were read to. Heady experience, that. And Wodehouse fits Lithgow’s reading skills so perfectly, it’s as if they were one. And, indeed, when a writer’s words get into you and then start coming out of you, that is exactly what should happen. Of course, having heard Lithgow read that story so brilliantly, one wants “more.”

The story Lithgow has chosen for the second half – “Haircut” by Ring Lardner – is actually the better story in every way, as literature and as an exercise for a great actor, since the story is told in the time it takes for its narrator, a barber from a small town in the mid-west, to give his customer a shave and a haircut. And, since it is basically a monologue and its central character is drawn with a profound understanding of who he is and what the world around him is like, there is room here for a subtle creation that Lithgow could surely make his own. The surprise is that he doesn’t. Instead of becoming the barber, Lithgow gives us a blueprint of the character. It is a vivid blueprint, rich in human potential, but it is nevertheless a blueprint, not yet brought to life on the stage. Instead, what we get is Lithgow acting the part, a bit too self-consciously, a bit too fussily in terms of his pantomime of a barber constantly lathering, honing his razor on a strop, washing his hands, cutting hair, shaving with delicate care not to nick the customer. But we don’t smell the talcum or the Vitalis. And the barber’s laughter – a thing of beauty when first heard – becomes a tiresome shtick. If and when Lithgow finds, as he does so wonderfully in Wodehouse, the key to what makes Lardner’s story so good, and he becomes the barber, then “more” will definitely be “more.”

Perhaps the reason Wodehouse works so well is because it is connected to a personal story about his family. The Lardner is a great story and Lithgow knows it, but its reason for existence comes less from personal experience than from an actor’s desire to create a honey of a part. An actor as good as Lithgow could play that part easily. He’s working too hard at it at the moment. But that first half of Stories By Heart is theatrical heaven both for the child in us and the adult in us.

harveyperr @ stageandcinema.com

photo by Joan Marcus

Stories By Heart

scheduled to close February 13 at time of publication

for tickets, visit http://www.centertheatregroup.org/stories