VARIATION ON 33 VARIATIONS

Since I feel pretty much the same as I did when I first saw 33 Variations, and since it is virtually the same production with virtually the same cast, I have decided to reprint my original review, along with an addendum that follows afterward.

—

THE CURIOUS CASE OF LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

originally published March 13, 2009

Why was Ludwig van Beethoven, totally deaf by then and ill with vomiting and diarrhea, having completed his Ninth Symphony and his Missa Solemnis, still fussing with his variations on a trifling oom-pah waltz by the third-rate composer (and first-rate music publisher) Anton Diabelli? In his driven desperation and in his dementia – his bed clothes in sickly disarray and his body achingly feverish – he makes an attempt to get to the heart of the thirty-second variation, and, in the process, he may not give us the answer to the question, but he does, in the wholly convincing performance of Zach Grenier, let us glimpse into the mad genius we are sure Beethoven must have been. In the daring complexity of that moment, something of what Moisés Kaufman is after in his fascinating and intricately layered 33 Variations comes shining through.

But we must go back to the beginning. Dr. Katherine Brandt, a brilliant musicologist, dying of the degenerative disease Lou Gehrig has given his name to, goes to Bonn to look through Beethoven’s papers and to write her thesis on this perplexing question: why would a genius become obsessed with such a trifle? The closer she gets to the answer, the closer she is to her own death. And, of course, Dr. Brandt has become as obsessed with the question as Beethoven had come obsessed with that waltz. It should come as no surprise – especially when you consider that both Beethoven and Brandt are in the twilight of their lives – that the more one’s life unravels, the closer one gets to the simple basics. It may be a sentimental notion, but it is worth investigating with the heart-stopping thoroughness that Kaufman demonstrates. Kaufman doesn’t write conventional plays. He constructs experiences which evolve through the special ingenuity of theatrical presentation.

In his own work – Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde and The Laramie Project – and in Doug Wright’s I Am My Own Wife, which he staged so mesmerizingly, homosexuality was at the center of those particular constructions, which touched them with personal passion. That particular freshness is missing in 33 Variations, but the passion to put on stage something probing and elusive is still part of the Kaufman equation. He gets inside Beethoven’s world with unerring verisimilitude and both in the writing of the characters – Beethoven, Diabelli, and Beethoven’s assistant Anton Schindler – and the playing – by Grenier, Don Amendolia, and Erik Steele [Grant James Varjas in the current production]– their particular universe travels though the play with richness and wit.

In his own work – Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde and The Laramie Project – and in Doug Wright’s I Am My Own Wife, which he staged so mesmerizingly, homosexuality was at the center of those particular constructions, which touched them with personal passion. That particular freshness is missing in 33 Variations, but the passion to put on stage something probing and elusive is still part of the Kaufman equation. He gets inside Beethoven’s world with unerring verisimilitude and both in the writing of the characters – Beethoven, Diabelli, and Beethoven’s assistant Anton Schindler – and the playing – by Grenier, Don Amendolia, and Erik Steele [Grant James Varjas in the current production]– their particular universe travels though the play with richness and wit.

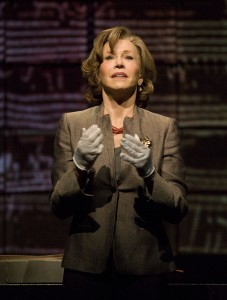

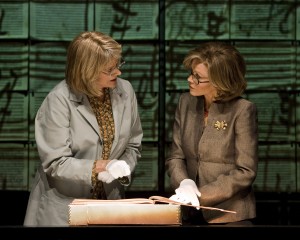

If Kaufman has found solace and truth in Dr. Brandt’s compulsions, he has walked away a bit from what makes her a fully realized human being, but he has had the good fortune to have Jane Fonda lend her great strengths as an actress to bring to vivid life her character. It is a compliment, too, to Ms. Fonda’s intelligence that she has chosen to return to the Broadway stage in a play that ignores the easy and the conventional. It is true that, when she is in the final ravages of her disease, she continues to look beautiful, when one might wish that she would make tougher demands on herself as an artist and depict her gradual deterioration. It is here that Beethoven stands in for Brandt, and Grenier shows us what Fonda won’t. It is not that Fonda doesn’t go from interior steeliness to physical uncertainty to creating the illusion of slowly withering away. She does. At any rate, the point gets made without losing subtlety.

If Kaufman has found solace and truth in Dr. Brandt’s compulsions, he has walked away a bit from what makes her a fully realized human being, but he has had the good fortune to have Jane Fonda lend her great strengths as an actress to bring to vivid life her character. It is a compliment, too, to Ms. Fonda’s intelligence that she has chosen to return to the Broadway stage in a play that ignores the easy and the conventional. It is true that, when she is in the final ravages of her disease, she continues to look beautiful, when one might wish that she would make tougher demands on herself as an artist and depict her gradual deterioration. It is here that Beethoven stands in for Brandt, and Grenier shows us what Fonda won’t. It is not that Fonda doesn’t go from interior steeliness to physical uncertainty to creating the illusion of slowly withering away. She does. At any rate, the point gets made without losing subtlety.

Where Kaufman fails, it is in the writing of the third main character, Dr. Brandt’s daughter. It is interesting theatrically to see a third element weave itself into the proceedings, but it is inert dramatically; the attempts to turn this strong-willed woman – who constantly fights her mother and who eventually is responsible for leading her into the light – into a recognizable person are still-born. And her relationship with a male nurse is television-simple and so predictable it seems to have come from another play, one not written by Kaufman. Samantha Mathis and Colin Hanks [Greg Keller in the current production] bring intelligence and humor to the parts, but they are shackled by the flat-footedness of the writing. Dr, Brandt has a much stronger relationship with her German doctor – played briskly and warmly by Susan Kellermann – than she does with her daughter.

33 Variations is, despite its failure to make something honest and true of one of its pivotal characters, an ultimately moving drama. And it is moving without losing any of its cerebral underpinnings. And it also gives us a great Beethoven in Zach Grenier. And it brings back to the theater the remarkable Jane Fonda. All in all, an impressive addition to the Broadway season.

—

The February 2011 addenda:

1) There have been two major cast changes; one works, the other doesn’t (the one that does, Greg Keller – in the pivotal role of the male nurse with whom Dr. Brandy’s daughter has a relationship – manages, despite an initial attempt to define the character in comic terms, to turn a less-than-convincingly-written role into a full human being, and it gives Samantha Mathis someone to play against; the one that doesn’t, Grant James Varjas – as Beethoven’s assistant Schindler – has not yet found, as the marvelous Zach Grenier and the delightful Don Amendolia have, the perfect balance between truth and exaggeration);

2) Jane Fonda is even better now, particularly in the second half, where her steady physical deterioration is delineated with intensity and skill, making her desperation to complete her thesis more palpable;

3) While nothing will alter my opinion that the Ahmanson is just too big a space for a play that is this intimate, thereby giving the impression that the play is far more epic than it really is, it is still serious work that deserves a hearing, and this is pretty much as good as commercial theater gets;

4) The production is quite handsome and rich with a sense of the play’s musicality, thanks largely to the always striking collaboration between Derek McLane, who designed the sets, and Jeff Sugg, who created the eloquent projections.

photos by Craig Schwartz

33 Variations

Music Center’s Ahmanson Theatre, 135 N. Grand Ave.

ends on March 6, 2011

for tickets, call 213.972.4400 or visit CTG

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Harvey, I have wanted to thank you for quite a while now for your thoughtful, intelligent, clean, ‘understandable’, direct reviews — whether I agree or not, they are so very well-written and much appreciated!

Thank you!