WHAT EVER HAPPENED TO LANFORD WILSON?

The beautifully detailed lower Manhattan loft that Ralph Funicello has created – complete with fire escape and skylight, unfinished walls daubed with swatches of paint – for the revival of Lanford Wilson’s Burn This takes one’s breath away as one settles into one’s seat. But, as the saying goes, you can’t leave a theater humming the set. Not without feeling slightly cheated about the rest of the evening, anyway. You can’t help but wonder what happened to the play.

There was a time when the Lanford Wilson I knew and loved – back in the days of The Hot L Baltimore and Balm In Gilead and The Rimers Of Eldritch – showed a compassion for the disenfranchised, a breathtaking talent for turning common conversation into uncommon theatrical language, an equally uncanny ability – through his inspired use of overlapping – to create the illusion of life’s natural rhythms. It wasn’t always important what his characters said; it was the way in which they said it that breathed refreshing new life into old forms, and made him, at the time, the heir apparent to the two playwrights he revered the most: Tennessee Williams and Anton Chekhov.

There was a time when the Lanford Wilson I knew and loved – back in the days of The Hot L Baltimore and Balm In Gilead and The Rimers Of Eldritch – showed a compassion for the disenfranchised, a breathtaking talent for turning common conversation into uncommon theatrical language, an equally uncanny ability – through his inspired use of overlapping – to create the illusion of life’s natural rhythms. It wasn’t always important what his characters said; it was the way in which they said it that breathed refreshing new life into old forms, and made him, at the time, the heir apparent to the two playwrights he revered the most: Tennessee Williams and Anton Chekhov.

And then he wrote his most commercially successful play, Burn This, and it became the demarcation point in the history of every play that preceded it and every play that followed it. But the question now is: To what end? In a New York production a few years back with Edward Norton and Catherine Keener in its leads, every line of dialogue was treated as if it were written by William Shakespeare and the long pauses between each line merely emphasized the fact that the dialogue, in and of itself, actually succeeded in destroying the illusion of real speech that Wilson was always, painstakingly and with great relish, trying to create. Instead, the impression was given that there was not much of a play there at all. In the current revival at the Mark Taper Forum (which produced the original production with John Malkovich, Joan Allen, and Lou Liberatore), director Nicholas Martin doesn’t make the same mistake – this production moves swiftly and painlessly – but he can’t disguise the fact that the play doesn’t seem to be going anywhere, however quickly (or slowly) it moves. One can’t help but wonder if the play’s great success was totally dependent on the galvanizing presence of Malkovich as Pale, the play’s protagonist, and of the way the danger he brought to the stage, in turn, brought out in his fellow actors the impression of a shared experience that must have been wildly liberating. What other explanation can there be? I know of nobody who saw Malkovich who didn’t feel that way. But, in both its revivals, it has come nowhere near that kind of sensation. In fact, it has done just the opposite.

And then he wrote his most commercially successful play, Burn This, and it became the demarcation point in the history of every play that preceded it and every play that followed it. But the question now is: To what end? In a New York production a few years back with Edward Norton and Catherine Keener in its leads, every line of dialogue was treated as if it were written by William Shakespeare and the long pauses between each line merely emphasized the fact that the dialogue, in and of itself, actually succeeded in destroying the illusion of real speech that Wilson was always, painstakingly and with great relish, trying to create. Instead, the impression was given that there was not much of a play there at all. In the current revival at the Mark Taper Forum (which produced the original production with John Malkovich, Joan Allen, and Lou Liberatore), director Nicholas Martin doesn’t make the same mistake – this production moves swiftly and painlessly – but he can’t disguise the fact that the play doesn’t seem to be going anywhere, however quickly (or slowly) it moves. One can’t help but wonder if the play’s great success was totally dependent on the galvanizing presence of Malkovich as Pale, the play’s protagonist, and of the way the danger he brought to the stage, in turn, brought out in his fellow actors the impression of a shared experience that must have been wildly liberating. What other explanation can there be? I know of nobody who saw Malkovich who didn’t feel that way. But, in both its revivals, it has come nowhere near that kind of sensation. In fact, it has done just the opposite.

The drama, such as it is, depends on the character of Pale and how he affects the people into whose lives he callously stampedes. In the aftermath of a tragic accident that has killed Robbie, a gay young dancer/choreographer (as well as his lover), the dancer’s brother, Pale, shows up at the loft where Robbie lived, banging on the door at an unearthly hour, roaring drunk, too self-absorbed to show any sense of heartbreak over his brother’s death. The dancer’s roommates – an insecure dancer, Anna, who may have been secretly in love with the gay dead man, and the acerbic gay Larry, who may have also been (not so) secretly in love with him – are both repelled and fascinated by this repellant and fascinating creature, whose only resemblance to his dead brother is physical. But, for Anna, the physical resemblance may be enough; with Pale, unlike his brother, sex is possible. Anna’s need for Robbie, the gay brother, needed sublimation (which she finds with the otherwise uninteresting man she’s dating, Burton); her desire for Pale becomes palpable. For all the crazily brilliant and implosively wounding words that Wilson supplies Pale with in the fantastic rants he goes on,

The drama, such as it is, depends on the character of Pale and how he affects the people into whose lives he callously stampedes. In the aftermath of a tragic accident that has killed Robbie, a gay young dancer/choreographer (as well as his lover), the dancer’s brother, Pale, shows up at the loft where Robbie lived, banging on the door at an unearthly hour, roaring drunk, too self-absorbed to show any sense of heartbreak over his brother’s death. The dancer’s roommates – an insecure dancer, Anna, who may have been secretly in love with the gay dead man, and the acerbic gay Larry, who may have also been (not so) secretly in love with him – are both repelled and fascinated by this repellant and fascinating creature, whose only resemblance to his dead brother is physical. But, for Anna, the physical resemblance may be enough; with Pale, unlike his brother, sex is possible. Anna’s need for Robbie, the gay brother, needed sublimation (which she finds with the otherwise uninteresting man she’s dating, Burton); her desire for Pale becomes palpable. For all the crazily brilliant and implosively wounding words that Wilson supplies Pale with in the fantastic rants he goes on,  the play is really about Anna, and yet, in the writing, she is the weakest part of the equation in Burn This; her passivity forces her to face her desperation in a vacuum, unless we are made to understand and feel her pain.

the play is really about Anna, and yet, in the writing, she is the weakest part of the equation in Burn This; her passivity forces her to face her desperation in a vacuum, unless we are made to understand and feel her pain.

What is most missing in the production – and, without it, even the possibilities of dramatic action are stillborn – is the sense of the lives the characters have lived prior to their entrance on stage. We are in the moment, and, unfortunately, the moments, as they pile up, are too removed from even our casual interest. They seem merely a succession of theatrical flourishes. If the drinking the play is drenched in had revealed deeper truths about the people, there might have been some forward propulsion, but, as it stands, the play is more intoxicated than intoxicating. And, in the character of Larry, the play is slightly gay but also slightly homophobic.

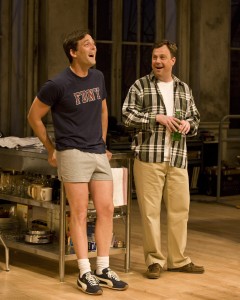

Again, none of this would have mattered if the actors had been permitted to express their inner lives. In the Norton-Keener edition, the humanity was there, but the craziness was muted. What is needed is the perfect blending of craziness and humanity. Here, all we get is the craziness. It works, on some cheap level, but it makes a strong case against the play as a work of serious art. Adam Rothenberg’s Pale is all dazzle and little depth. Zabryna Guevara’s Anna is cool and inscrutable. The heat between them is the heat between actors, not the heat between two needy and tortured people. And the Larry which Brooks Ashmanskas gives us is such a stock caricature of a gay man who can’t say anything that isn’t self-consciously “witty” that it is practically a Kabuki performance in which surface mannerisms are meant to tell us everything we need to know; but where is the breaking heart that his “wit” conceals? And, since Rothenberg and Ashmanskas are letting all the stops out, one would think that Ken Barnett, in the part of the straight but not altogether straight Burton, would be reined in,

Again, none of this would have mattered if the actors had been permitted to express their inner lives. In the Norton-Keener edition, the humanity was there, but the craziness was muted. What is needed is the perfect blending of craziness and humanity. Here, all we get is the craziness. It works, on some cheap level, but it makes a strong case against the play as a work of serious art. Adam Rothenberg’s Pale is all dazzle and little depth. Zabryna Guevara’s Anna is cool and inscrutable. The heat between them is the heat between actors, not the heat between two needy and tortured people. And the Larry which Brooks Ashmanskas gives us is such a stock caricature of a gay man who can’t say anything that isn’t self-consciously “witty” that it is practically a Kabuki performance in which surface mannerisms are meant to tell us everything we need to know; but where is the breaking heart that his “wit” conceals? And, since Rothenberg and Ashmanskas are letting all the stops out, one would think that Ken Barnett, in the part of the straight but not altogether straight Burton, would be reined in,  but he seems eager to compete with his confederates on their terms, going overboard when a sense of sanity and sobriety is needed. These are all talented people, but their techniques and disciplines seems to be at variance with each other, without the human connection that should be (but isn’t) de rigeur.

but he seems eager to compete with his confederates on their terms, going overboard when a sense of sanity and sobriety is needed. These are all talented people, but their techniques and disciplines seems to be at variance with each other, without the human connection that should be (but isn’t) de rigeur.

Wilson’s death was tragic news; what one longed for was a fitting tribute to his gifts. Instead, his most famous play has been reduced to a hyped-up, drunken, gay version of a boulevard comedy, complete with a happy ending.  He deserved better. One wishes that it might have been one of the early plays that was revived (more about the failure of the later plays at another time). Of course, nobody could have predicted, when Burn This was put on the seasons’ schedule, that Wilson would no longer be with us when it opened. I guess the Taper, like Wilson, was going for the “big orchestrations” when “sittin’ here, makin’ polite conversation about the state of the world and shit” was more than enough.

He deserved better. One wishes that it might have been one of the early plays that was revived (more about the failure of the later plays at another time). Of course, nobody could have predicted, when Burn This was put on the seasons’ schedule, that Wilson would no longer be with us when it opened. I guess the Taper, like Wilson, was going for the “big orchestrations” when “sittin’ here, makin’ polite conversation about the state of the world and shit” was more than enough.

harveyperr @ stageandcinema.com

photos by Craig Schwartz

Burn This

scheduled to close May 1 at time of publication

for tickets, visit http:// www.centertheatregroup.org