WHAT AN ABSURD WEEKEND

EXISTENTIALISM 101 & THEATRE OF THE ABSURD

You’re watching a play but you have no idea what’s happening. There is no plot, the dialogue is gobbledygook, and characters are filled with despair, yet you are told that this is Theatre of the Absurd, one of the milestones in modern drama. Still more maddening is that others around you can’t believe you don’t “get it,” yet very few of them can explain just what “absurdism” is.

Part of the delicious attraction to Theatre of the Absurd – and the philosophy of existentialism that gave birth to this style of theatre – is that it frees us from having to explain anything. This freedom – this acknowledgement that life is a riddle that is inside a mystery, which is inside an enigma, which is inside a question – actually incites passion to live life to the fullest. After all, mankind is festooned with belief systems that didn’t bring peace to the generations we inherited them from – why should we adhere to them?

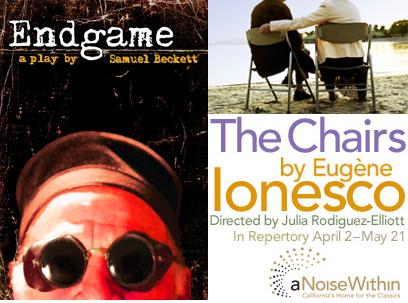

The productions that I saw this week illuminate just why Absurdist Drama is so baffling for many a theatregoer. There will be a disparity of reactions from audience members: some will salivate at each hidden reference in Samuel Beckett’s Endgame (now on at Sacred Fools) and Eugene Ionesco’s The Chairs (at A Noise Within), sitting on the edge of their seats as characters humorously grapple with the meaninglessness of existence. Others will slump down in a nonplussed state of ennui, staring at their watches for the umpteenth time long after they’ve asked themselves just what in the depressing hell is going on’¦even though both productions clock in at under 90 minutes.

Both productions were produced with the highest of standards, but they were frustrating for different reasons: The Chairs seems antiquated – fascinating in structure but lacking in resonance. That, combined with a deficiency of humor and eeriness, kept me from connecting with the show. Endgame is far more successful, utilizing humor and a sensational lead actor, but a paint-by-numbers approach on a gorgeous set only heightens how difficult the piece is to produce.

More on the shows later. First, an elucidation of both Theatre of the Absurd and existentialism are hereby presented so that you may have a greater appreciation of what you are – or are not – seeing on the stage.

* * * * * * * *

In his 1942 essay, The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus (playwright of Caligula) put forth his theory of the “absurd,” asserting that the human being is on a useless quest for meaning, harmony, and lucidity in a world where we have no way of actually knowing whether or not God or eternal truths exist. The absurd occurs when the human looks for meaning in a meaningless existence; our need for explanation will always collide with an unreasonable and unjust world.

In his 1942 essay, The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus (playwright of Caligula) put forth his theory of the “absurd,” asserting that the human being is on a useless quest for meaning, harmony, and lucidity in a world where we have no way of actually knowing whether or not God or eternal truths exist. The absurd occurs when the human looks for meaning in a meaningless existence; our need for explanation will always collide with an unreasonable and unjust world.

The belief that life is absurd can assist us in detaching ourselves from this fruitless search. By doing so, we create a heightened awareness which makes us open to new experiences; this, in turn, helps us to get more out of life.

Camus (pictured above), who admired those who rebelled against the absurdity of existence, said: “You will never be happy if you continue to search for what happiness consists of. You will never live if you are looking for the meaning of life.” The benefits of learning to live with the absurd are revolt, freedom, and passion. Ignore the conflict, and your choices are either suicide or the inadequacy of hope.

In a 1960 essay, critic Martin Esslin (pictured above), who adopted the word “absurd” from Camus, created the term Theatre of the Absurd to name that which had already taken place in the plays of Beckett, Adamov, Ionesco, and Genet. In essence, Absurd Drama presents a godless universe where human existence has no meaning or purpose – therefore, all communication breaks down. Rational construction and argument give way to foolish and illogical speech, ultimately concluding in suicide or silence (or both, as we discover in The Chairs).

The authors associated with The Absurd eschew rational playwriting because they are more concerned with expressing their vision of a world that lacks cohesion. As such, even language itself is viewed as confining, so the dialogue can be ludicrous and static; or, in the case of Harold Pinter (pictured below), contain long pauses of dialogue-rich silence, elucidating just what we are really saying to one another in life: nothing.

Generally, Theatre of the Absurd presents a disillusioned, harsh, and stark picture of the world (yet the plays can often be very funny). This, combined with seemingly senseless stage scenarios and nonsensical dialogue, is why the plays can be inaccessible and difficult to comprehend, and therefore off-putting for some.

Absurdist Dramatists are notorious for demanding that shows not be altered or experimented with – the setting (such as an old sheet on two ashbins in Endgame) and stage directions (such as “brief tableaux”) are to be strictly adhered to: Beckett, Harold Pinter (The Homecoming), and Edward Albee (Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?) have all sued theatre companies for not presenting the play exactly as written. Thus, it takes a true visionary and astounding casting to make Theatre of the Absurd palatable.

So why does this theatre exist and why should we care? To answer that, I offer you Existentialism 101:

Regardless of how indomitable the human spirit can be, inequity and intolerance can enervate even the hardiest of souls. In a world teeming with greed, terrorism, and unrest, we look for deities and scientific institutions to explain the harsh realities of life. Some look outside themselves for a miracle that would ease their  suffering, yet New Age philosophies advocate that miracles occur as a result of a shift in one’s perception, not from an outside force. Philosophies can tweak our thought patterns in such a way that our spirit is reinvigorated when the culture we live in chips away at our resilience.

suffering, yet New Age philosophies advocate that miracles occur as a result of a shift in one’s perception, not from an outside force. Philosophies can tweak our thought patterns in such a way that our spirit is reinvigorated when the culture we live in chips away at our resilience.

The same could be said of religion, which is why the many forms of existentialism focus on matters such as choice, individuality, subjectivity, free will, and the nature of existence itself. However, there are Christian existentialists who believe that God challenges human beings to act as free and responsible, even though one’s actions can still lead them to Hell, which is exactly where Jean-Paul Sartre’s characters end up in No Exit (Sartre states that Hell is other people).

The basic tenet of existentialism is that we have the freedom to choose what we become. Life is meaningless – there is no Divine Plan, and events are random and seem even cruel. It stands to reason, therefore, that man is responsible for his own thoughts and actions. However, this responsibility of decision, action, and beliefs can overwhelm the individual, thereby causing profound anxiety. This angst fuels our desire to blame somebody or something else for our situation.

However, denying responsibility only leads to self-deception and isolationism. At any rate, existentialism recognizes that alienation is a natural by-product of modern life: it is unavoidable since living is a series of interactions with other human beings and their choices. For that reason, we should not examine our lives as “good” or “bad” but whether or not we are living our lives authentically; self-awareness is mandatory. Regardless of the debate as to the essentials of existentialism, the focus is on the individual. (If you think that all of this is a mind-fuck, wait until you’re sitting in the theatre.)

However, denying responsibility only leads to self-deception and isolationism. At any rate, existentialism recognizes that alienation is a natural by-product of modern life: it is unavoidable since living is a series of interactions with other human beings and their choices. For that reason, we should not examine our lives as “good” or “bad” but whether or not we are living our lives authentically; self-awareness is mandatory. Regardless of the debate as to the essentials of existentialism, the focus is on the individual. (If you think that all of this is a mind-fuck, wait until you’re sitting in the theatre.)

From the Bible to Milton, writers have incorporated existentialism into their work, completely unaware that there would one day be a word to categorize their efforts. In the decades surrounding World War II, Europeans had had enough of war and the impingement of freedom by industrialists and oppressive dictatorships, so it was natural that they were inherently hostile toward theoretical systems. Up to then, existential beliefs were largely a debate; now the philosophy fueled a call for social change.

The clincher that established existentialism as a movement began with Sartre, who declared that existence comes before essence, contradicting many philosophies up to that time. In other words, what you are is not a birthright; it is a product of your choices. His ideas, based on existential philosophy, became so entrenched in fine arts that some now see existentialism as a literary movement. Along with Sartre  (pictured here), authors belonging to this existential literati were Simone de Beauvoir, Kafka, Marcel, Dostoevsky, and, earlier, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche.

(pictured here), authors belonging to this existential literati were Simone de Beauvoir, Kafka, Marcel, Dostoevsky, and, earlier, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche.

Camus staunchly denied being a philosopher, let alone an existentialist, calling it “philosophical suicide.” It may be said that existentialism acknowledges the absurd, but searches for some sort of transcendence from the absurd itself. Theatre of the Absurd, on the other hand, concentrates on man’s failure to accept the absurd. Camus insists that the logic of the absurd demands that there be no reconciliation or transcendence. This is crucial, my dear theatergoers: there will be no resolution on stage to the dissatisfaction caused by one’s confrontation with an absurd world; thus, Absurdist Drama offers no tidy endings. It is an opportunity for you to relieve yourself of the futile search for answers by living in the question. My sense is that Beckett and Ionesco, both expatriates to Paris (where their plays premiered), were far less interested in “where we go from here” and more concerned with the folly of mankind that led to the dehumanizing wars of the twentieth century.

* * * * * * * *

Thus, it is with a nod to absurdism that I cannot resolve my own dissatisfaction with A Noise Within’s production of The Chairs. I thought it was the play that baffled me, but upon closer inspection, it was the production itself.

Thus, it is with a nod to absurdism that I cannot resolve my own dissatisfaction with A Noise Within’s production of The Chairs. I thought it was the play that baffled me, but upon closer inspection, it was the production itself.

In what may be a post-apocalyptic world, an old couple prepares for the arrival of an orator, who will presumably give a lecture based on the Old Man’s “discovery,” which implicates that the Old Man has figured out the meaning of life. The two enigmatically muse over their lives as their invisible guests (who may or may not be real) exponentially arrive at the island dwelling – suggesting that these two elderly folk may be the last people on earth. Well, the joke’s on us as a flesh-and-blood orator does arrive. The couple agrees that life could not get any better and they jump to their death, leaving behind an orator who turns out to be a deaf-mute.

Finally, we are left to watch the confetti-strewn, empty chairs stare back at us; this expression of absence is the last defining moment in the show. In order for us to connect with the sadness, despair and emptiness of the moment, it is mandatory that we miss the two characters we just spent ninety minutes with. To paraphrase Ionesco (pictured below), this void must come to life upsetting logic and raising fresh doubts. But it does not.

Deborah Strang, as the Old Woman, is astounding to watch as she navigates numerous entrances and exits, manically maneuvering a myriad of seating apparatuses, including Porta Potties (credit Stephen Gifford for those exquisitely designed, antiqued chairs). While she is at turns dotty, silly, libidinous and motherly, Ms. Strang’s Dorothy Louden-esque shenanigans exude a hint of what this production sorely lacks: slapstick humor.

In spite of the nightmarish atmospheres he created, Ionesco identified his “creative ancestors” as the Marx Brothers, Charlie Chaplin and the Keystone Cops. Since the dialogue is filled with non-sequiters and occasional gibberish, The Chairs screams for a Vaudevillian repartee between the nonagenarian couple, maybe like Burns and Allen on steroids.

Geoff Elliot’s approach to the Old Man is quite straight-forward and he seems too young, even with the beautiful make-up by Monica Lisa Sabedra. He should be a combination of the deadpan glee of John Gielgud and the manic vulnerability of Zero Mostel. No one doubts Mr. Elliot’s capabilities; he is simply miscast.

Thus, the actors seem to be playing at odds with the moribund script. The characters are so intentionally void in psychological motivation that we can muster up no more sympathy for them than we can for the invisible guests. Their bent towards realism only heightens the confusion inherent in this tragicomedy. At one time, the very nature of the script may have been scandalous and shocking, but for a modern audience, perhaps director Julia Rodriguez-Elliot needed to add shtick, shtick and more shtick.

When the doors to the couple’s home bursts open towards the end of the show, a shroud of fog unsettlingly slithers into the audience, raising one more necessity: a creepiness factor. These people and civilization are near-death, but the antediluvian set (Mr. Gifford), tattered costumes (Kellsy MacKilligan) and the beautiful lighting (Ken Booth) should scream of fetid decay, not just dilapidation. When the orator arrives, I was hoping that the actor, Andy Stokan, would have an appearance that chills us to the bone – like Munch’s existential masterpiece, “The Scream” – instead, Mr. Stokan looked quite ordinary.

The Chairs misses the opportunity to be cutting-edge theatre; lovers of Absurdism may yet find enough joy in Ionesco’s words, but those who are unfamiliar with the work risk being bored out of their skulls.

* * * * * * * *

In Endgame, the end of the world is upon us. Four characters inhabit a squalid little room where the blind and disabled master Hamm (Leon Russom) barks orders from a castered throne to his servant Clov (David Fraioli), who may also be Hamm’s son. (Some critics say yes, some say no. I say that it doesn’t matter, just be in the question.) Hamm cannot stand up and Clov cannot sit. Their relationship is somewhat like that of George and Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? – you can tell that they have been arguing for years, but that dynamic seems to be the raison d’etre of their relationship – they feed on game-playing and one-upping each other as to “who” needs “who” more:

HAMM: Why do you stay with me?

CLOV: Why do you keep me?

HAMM: There’s no one else.

CLOV: There’s nowhere else.

And later in the play:

CLOV: So, you all want me to leave you.

HAMM: Naturally.

CLOV: Then I’ll leave you.

HAMM: You can’t leave us.

CLOV: Then I won’t leave you.

Clov constantly threatens to leave, but in the end, he stands with possessions in hand, watching the man who dominates him. Besides, where would he go? The outside world is desolation and Clov’s red face hints at the chemical destruction in the world.

Clov constantly threatens to leave, but in the end, he stands with possessions in hand, watching the man who dominates him. Besides, where would he go? The outside world is desolation and Clov’s red face hints at the chemical destruction in the world.

Disconnection? Radiation? Master/Slave relationships? Disillusionment? Preoccupation with death? One would think that Endgame was written yesterday, so topical are its themes. Beckett (pictured here) must have been joking when he denied that his play takes place in a post-nuclear world, where even death itself carries no meaning. In fact, Hamm shows no surprise when his mother Nell (Kathy Bell Denton) emerges from an ashbin to reminisce with her husband Nagg (Barry Ford), only to slink back into her ashbin and die.

As Hamm, Mr. Russom is splendid – a brilliant combination of theatricality, fear, remorse and playfulness. With a rich baritone, his lush, expressive voice commands our attention. What is most uncanny is that you feel you are looking him right in the eyes, yet they are hidden behind dark glasses. His is the performance that makes this Endgame recommendable.

Are the other performers bad or in any way misguided? No. Yet, they are not riveting. There is a longing for personalities that have an other-worldly distinction which makes the cryptic dialogue, however seemingly obtuse for some, simply entertaining.

You see, Beckett himself described Endgame as “rather difficult and elliptical.” Lucky is the critic who sees Biblical parables, death of Western civilization, polarities of existence, and other such perceived contrivances, but Beckett warned us that it was useless to try and find meaning in his work, especially symbolic meaning.

No meaning? Maybe. But Beckett certainly incorporates references. Since many audience members may not even comprehend that the play’s title is a term in chess, they must have something more than a deliriously beautiful set (Tifanie McQueen) and some fine nuances in the dialogue (director Paul Plunkett). We must have unique souls on stage; Mr. Ford, Ms. Denton and Mr. Fraioli all do their jobs well, but their idiosyncratic characteristics are not enough to make this Endgame transcendent. I dare say that devotees of Endgame will be pleased with the results at Sacred Fools, but, as with The Chairs, those unfamiliar with Beckett may find your mind wandering into a nothingness beyond the nothingness on stage.

The goal of absurdist drama is an attempt to assist audiences in comprehending their own “meaning” in life. Without a firecracker of a production, the inherent negativity of Theatre of the Absurd can be depressing. God knows (oops, I mean, Nothing knows) that it’s a real bitch to pull off a spellbinding production. After all, visionaries of the theatre are dealing with a playwright who said, “Nothing is more real than Nothing.”

tonyfrankel @ stageandcinema.com

The Chairs

A Noise Within in Glendale

ends May 21, 2011

for tickets, call 818.240.0910 or visit A Noise Within

photos by Craig Schwartz

Endgame

Sacred Fools in Hollywood

ends April 23, 2011

for tickets, call 310.281.8337 or visit Sacred Fools

photos by Ben Rock

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Tony, I just wanted to let you know how much I love your reviews. I see lots of theater and although I think we have a number of excellent critics in LA I have come to depend on your reviews. I just wish your reviews came out sooner so I could plan around them.

However, I saw The Chairs last night and while I agree with your approach to the play, I came to opposite conclusions. I did sympathize with the characters that I had just spent 90 minutes with – very much; and felt a deep loss when they took their lives. I found them endearing and shared their hope for a successful party where the truth would be revealed. Slapstick is indeed essential to this play and last night there was plenty of it and the timing between Strang and Eliott was exquisite. And, I think the ordinariness of the orator is essential to the play. He has to be all-too-human.