[NOTE: Film Critic Kevin Bowen is visiting his hometown – El Paso, Texas – and attending the third annual Plaza Classic Film Festival. The festival, running from Aug. 4 to Aug. 14, features 80 classic films. Bowen will write sporadic reports based on his viewing of the classic films as watched at the festival.]

NOT JUST MADDENING…BRILLIANTLY MADDENING

A man and a woman discuss a statue in a French garden. In the male stone figure, the man sees a protector, cautioning his wife against a danger up the road. The woman sees it differently: for her, the female figure has a spark in her eye from something that lies beyond.

Is this a statue of doom or fascination? The camera circles the stone. It picks apart the figures, examines them piece by piece: hand, foot, head, all outside of the context of the whole. Then we pull behind the figures to find a vast pool of water in front of them.

What is this body of water before them? Have they reached the sea? Is this what frightens or fascinates them? No and no, of course. We know the context. We know it’s not the sea, only a pool at a chateau, its position in front of the statue a seeming coincidence. How do we draw these lines of coincidence? Where does art end and reality begin? Where does the observer end and the observed begin?

Two men play a game. Set out on a table are cards, toothpicks, and finally, photographs. The only rule – the same man wins every time. The crowd spins theories as to this feat of domination. They try to wrestle this fact with words. The victories move forward, indifferent to explanation, game after game.

A woman receives a photograph. A man insists this photo was taken last year, maybe at Marienbad (maybe not), when the two were lovers (or were they not?), when they spun elaborate plans to run away together. The woman insists she does not remember. The man must be mistaken. How can he remember it so well, and how can she remember it not at all? The photo could be anywhere, anytime. Isn’t this proof? How can a woman staring at a camera grasp the entirety of a past?

They say one thing in one room, then run into the same words later on the balcony. The images have shaken free of the words; they follow their own drummer, circle back on themselves. Times change. Colors change. Details change. Never the same. Who are this man and this woman? Did they really meet one year ago? Did it happen? Is it happening now, if there even is a “now?” Are they flirting? Avoiding suspicion? Is he only the romantic fantasy of a lonely wife? Is she only the fictional muse of an artist who has thrust himself into his own story?

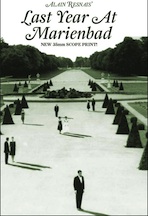

A mystery, wrapped in an enigma, baked into a delicate chocolate eclair, and placed in a vase at the center of a hedgerow maze for years, weeks, days, seconds, centuries – because really, when it comes to time, wouldn’t an artist say it’s all just a blink of an eye? – there is no way out of Alain Resnais’ brilliant, maddening, and brilliantly maddening Last Year at Marienbad. We glide through corridors of an ornate chateau that seem to have no end. The music swells and sharpens, dies and sharpens. A voice repeats a paragraph, fading in and out of sound. Shadowy men and women circle, chat, freeze. Are they real, ghosts, unstuck in time?

The architecture imitates the circular nature of the human mind – the way we visit an idea, consider the possibilities, visit the idea, draw a conclusion, inject a meaning, visit the idea, reopen the book, change our mind. Marienbad prefers this psychological reality over a linear and material reality – a baroque collage formed from imperfect fragments of memory, knowledge, speculation, intuition, fantasy, desire, nightmare, art and context.

Alain Robbe-Grillet, the co-writer of this script, was a noted mid-century French writer whose work was often noted for attacking the use of symbolism, preferring to analyze each thing as itself rather than as a stand-in for another. Why should an object have a second meaning when we’re not sure that it has a first? In writing, this meant long, descriptive passages about objects and a characters’ movements. In film, I think he has gone about it another way – by making the audience aware of how each member – like the couple theorizing about the statue – projects a psyche, a context, and ultimately a meaning onto the work of art. The film undermines meaning by making it clear that this meaning comes from us and not from it. The most important question about Last Year at Marienbad isn’t “what does it mean?” The most important question about Last Year at Marienbad is the question before – “Why does it have to mean anything at all?”

kevinbowen @ stageandcinema.com

Last Year at Marienbad

played at the Plaza Classic Film Festival in El Paso, Texas

for more on the festival (August 4-14, 2011), visit http://www.plazaclassic.com/