NO EXONERATION FOR AFTER

For the past decade, Partial Comfort has gained a reputation as one of the leaders in NYC’s downtown theater scene as a producer of new American plays. Instead of following the boundary breaking legacies of Albee, Shepherd, and Fornes, Partial Comfort’s production of Chad Beckim’s After, up and running at The Wild Project on the Lower East Side, is, ironically, heir apparent to the more middlebrow work produced by the Humana Festival circa 1979 (namely Marsha Norman’s Getting Out).

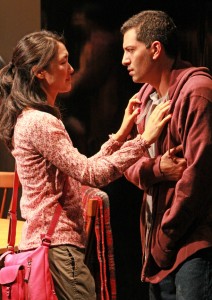

What the American theater has always done better than just about any other art form is to plumb the depths of the American character. Beckim has sketched a great character in Monty, After’s protagonist. When the play opens, Monty has returned home, just released from prison “after” seventeen years of doing time, exonerated by DNA evidence for a rape he did not commit. Beckim has wisely chosen the homecoming trope around which to structure his story. The play follows Monty as he adjusts to life outside prison, the loss of his youth, and the entreaties of the guilt-ridden woman who falsely accused him. Beckim is at his best when he shows us Monty as a fish out of water, reacting to excel sheets, computers, and overwhelming consumer choices for toothbrushes. It is a very poignant moment watching Monty on his first date getting his first kiss. Through the course of the play, Monty interacts with a quirky world, peopled with a fraught family member, a nerdy new boss, a meddling priest, a bully, and a neurotic lady-friend. An hour into After, one wonders if Beckim is implying that Monty might not be better off back in lock-up rather than navigating this world of annoying non-criminals.

What the American theater has always done better than just about any other art form is to plumb the depths of the American character. Beckim has sketched a great character in Monty, After’s protagonist. When the play opens, Monty has returned home, just released from prison “after” seventeen years of doing time, exonerated by DNA evidence for a rape he did not commit. Beckim has wisely chosen the homecoming trope around which to structure his story. The play follows Monty as he adjusts to life outside prison, the loss of his youth, and the entreaties of the guilt-ridden woman who falsely accused him. Beckim is at his best when he shows us Monty as a fish out of water, reacting to excel sheets, computers, and overwhelming consumer choices for toothbrushes. It is a very poignant moment watching Monty on his first date getting his first kiss. Through the course of the play, Monty interacts with a quirky world, peopled with a fraught family member, a nerdy new boss, a meddling priest, a bully, and a neurotic lady-friend. An hour into After, one wonders if Beckim is implying that Monty might not be better off back in lock-up rather than navigating this world of annoying non-criminals.

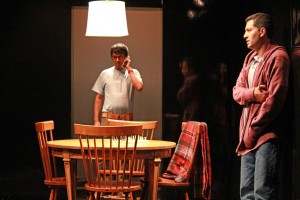

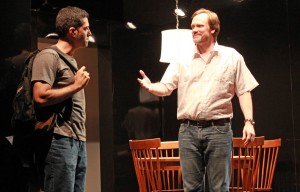

Unfortunately, Monty makes a great character but a lousy protagonist. In essence, Monty doesn’t do much dramatically. He gets a job with dogs, he asks a girl out, he ignores the woman who wrongfully accused him, and he gets by. He is like one of the anti-heroes from 70s cinema as he makes his way in the world, not sure of where he’s going, aimlessly reacting and responding. Beckim gives him a wide emotional palate to work with, from the brooding panther ready to spring to the mischievous kibitzer to a volcano of rage. But for all these feelings and situations, Beckim never lets us know Monty through an authentic dramatic incident of any resonance. Monty’s only redemption is that he is played by Alfredo Narciso, who gives a wonderful layered performance. For most of the play, he contains the rage of a life unlived; and when he finally does explode, it is a beautifully orchestrated, inevitable surprise. Narciso’s challenge is not to allow Monty to devolve into self-pity, as the unfairness of the situation does most of that work for him anyway. Watching Narciso’s Monty embrace and process his glass half-full while the world around him tries to get him to confront the half-empty past head-on, he elegantly creates a compassionate, humane portrait of a grieving man processing an untenable situation.

Unfortunately, Monty makes a great character but a lousy protagonist. In essence, Monty doesn’t do much dramatically. He gets a job with dogs, he asks a girl out, he ignores the woman who wrongfully accused him, and he gets by. He is like one of the anti-heroes from 70s cinema as he makes his way in the world, not sure of where he’s going, aimlessly reacting and responding. Beckim gives him a wide emotional palate to work with, from the brooding panther ready to spring to the mischievous kibitzer to a volcano of rage. But for all these feelings and situations, Beckim never lets us know Monty through an authentic dramatic incident of any resonance. Monty’s only redemption is that he is played by Alfredo Narciso, who gives a wonderful layered performance. For most of the play, he contains the rage of a life unlived; and when he finally does explode, it is a beautifully orchestrated, inevitable surprise. Narciso’s challenge is not to allow Monty to devolve into self-pity, as the unfairness of the situation does most of that work for him anyway. Watching Narciso’s Monty embrace and process his glass half-full while the world around him tries to get him to confront the half-empty past head-on, he elegantly creates a compassionate, humane portrait of a grieving man processing an untenable situation.

Of the supporting company, only Partial Comfort regular Andrew Garman as Chap, the meddling Priest, comes close to Narciso’s level of humanity. And even though the Chap/Monty scenes are the most grounded in the play, in Beckim’s world, Chap, who delivers letters, forms, and news, is more of a messenger-device than a fully realized character. The hallmark of Beckim’s other supporting characters is, regrettably, a lot of irritating chatter. Characters speak in monologues and paragraphs, rarely stopping to listen to others; and for people who talk so much, they have surprisingly little to say. In the first half of the play, Marie-Christina Oliveras is working much too hard as the anxious sister; but when she finally settles down in the second half, she brings the frustrated sister a heartfelt rage. Jackie Chung isn’t completely at fault as the annoyingly glib love interest, Susie – Beckim gives her some of the most cloying speeches of the night. But it’s DeBargo Sanyal who is the most mannered; it’s as if his Warren stepped out of a Big Bang Theory spoof. Because he paints his character with such broad comic strokes, it isn’t until the last moments of the play that he allows the audience to let us see Warren as a real person. With an otherwise able director like Stephen Brackett (and Judy Bowman in tow as casting director!), one wonders how After ended up with such an uneven ensemble.

Of the supporting company, only Partial Comfort regular Andrew Garman as Chap, the meddling Priest, comes close to Narciso’s level of humanity. And even though the Chap/Monty scenes are the most grounded in the play, in Beckim’s world, Chap, who delivers letters, forms, and news, is more of a messenger-device than a fully realized character. The hallmark of Beckim’s other supporting characters is, regrettably, a lot of irritating chatter. Characters speak in monologues and paragraphs, rarely stopping to listen to others; and for people who talk so much, they have surprisingly little to say. In the first half of the play, Marie-Christina Oliveras is working much too hard as the anxious sister; but when she finally settles down in the second half, she brings the frustrated sister a heartfelt rage. Jackie Chung isn’t completely at fault as the annoyingly glib love interest, Susie – Beckim gives her some of the most cloying speeches of the night. But it’s DeBargo Sanyal who is the most mannered; it’s as if his Warren stepped out of a Big Bang Theory spoof. Because he paints his character with such broad comic strokes, it isn’t until the last moments of the play that he allows the audience to let us see Warren as a real person. With an otherwise able director like Stephen Brackett (and Judy Bowman in tow as casting director!), one wonders how After ended up with such an uneven ensemble.

Yet Beckim must shoulder most of the blame. Without a dramatic incident for his main character, he leaves everyone onstage wandering aimlessly until a convenient act of violence sends the play to a conclusion. The program lists John Baker as dramaturge, so he should also be held accountable for the lack of cohesive ’¦ well, dramaturgy. At some point in the development process, the playwright/dramaturge collaboration should have confronted the elemental hole: this is a play without a dramatic incident, and it begs for one. Without the inevitable scene between Monty and his accuser, the audience is left completely unsatisfied. Beckim might be trying to tell us that no resolution is a kind of resolution, but that’s hardly new information (and, at this point in time, it’s dated post-modernism). Working within the genre of realism and leaving out that confrontation is either an act of dramaturgical laziness or subversion. Intent is immaterial; the result is that a potentially good play and great character is left without its peak dramatic incident. And the audience is sent home without its catharsis.

Yet Beckim must shoulder most of the blame. Without a dramatic incident for his main character, he leaves everyone onstage wandering aimlessly until a convenient act of violence sends the play to a conclusion. The program lists John Baker as dramaturge, so he should also be held accountable for the lack of cohesive ’¦ well, dramaturgy. At some point in the development process, the playwright/dramaturge collaboration should have confronted the elemental hole: this is a play without a dramatic incident, and it begs for one. Without the inevitable scene between Monty and his accuser, the audience is left completely unsatisfied. Beckim might be trying to tell us that no resolution is a kind of resolution, but that’s hardly new information (and, at this point in time, it’s dated post-modernism). Working within the genre of realism and leaving out that confrontation is either an act of dramaturgical laziness or subversion. Intent is immaterial; the result is that a potentially good play and great character is left without its peak dramatic incident. And the audience is sent home without its catharsis.

In spite of the shortcomings of the play and cast, Partial Comfort has still allowed director Stephen Brackett and his design team a chance to shine. Greg Goff’s lighting and Jason Simms’ sleek black set let the episodic nature of the world occur with an ambiguous sense of space. Great artistic value is made in not clearly letting one space completely end or another begin, echoing Monty’s vague perception of borders and limits in his new world. Equally effective is Daniel Kluger’s sound design (often slightly too loud), offering more subtle insights into Monty’s mind and perceptions. With a fraction of the bloated budget of an MTC or a Roundabout, Brackett and Company have created an elegant theatrical design on an Equity Showcase budget.

In spite of the shortcomings of the play and cast, Partial Comfort has still allowed director Stephen Brackett and his design team a chance to shine. Greg Goff’s lighting and Jason Simms’ sleek black set let the episodic nature of the world occur with an ambiguous sense of space. Great artistic value is made in not clearly letting one space completely end or another begin, echoing Monty’s vague perception of borders and limits in his new world. Equally effective is Daniel Kluger’s sound design (often slightly too loud), offering more subtle insights into Monty’s mind and perceptions. With a fraction of the bloated budget of an MTC or a Roundabout, Brackett and Company have created an elegant theatrical design on an Equity Showcase budget.

ta @ stageandcinema.com

photos by Yindy Vatanavan

After

The Wild Project

scheduled to end on October 8

for tickets, visit http://partialcomfort.org/