’˜TIS FOLLY TO OVERPRAISE FOLLIES

The buzz in the lobby of Chicago Shakespeare Theater (CST) on opening night of Stephen Sondheim’s landmark 1971 musical Follies was palpable; people from around the world were clamoring to see this rarely produced work – and for good reason. The original Broadway production is legendary: people lucky enough to see that Harold Prince/Michael Bennett version maintain that it was one of the most breathtakingly spectacular theatrical events ever, however problematic the libretto may have been (or should one say, still is).

It is more than prescient when James Goldman’s ever-so-sleight book has a waiter query a cynical broad with, “Hey, lady. What’s the matter?” To which she dryly retorts, “If I knew, I’d have it fixed.” After CST’s well-produced, occasionally thrilling but off-the-mark revival, we are left with a question no less existential than “What is the meaning of life.” And that is, can Follies ever work?

Director Gary Griffin’s scaled-down interpretation boasts a gigantic, talented cast of multi-generational Chicago performers (imagine the built-in nostalgia for locals), but while there are some show-stopping numbers, other numbers fall flat and the story leaves us feeling the same. We are entertained (supremely so in the latter half of the second act) even as we question the scenario and certain artistic choices.

Director Gary Griffin’s scaled-down interpretation boasts a gigantic, talented cast of multi-generational Chicago performers (imagine the built-in nostalgia for locals), but while there are some show-stopping numbers, other numbers fall flat and the story leaves us feeling the same. We are entertained (supremely so in the latter half of the second act) even as we question the scenario and certain artistic choices.

Yet the chance to see this many-headed Hydra of a show is rare and not to be missed, if just for the music alone. Anyone interested in the history of American Musical Theatre and the true beginnings of one of the greatest composer/lyricists in Broadway history should scamper, scuttle and scurry for tickets to this revival. Some may get drunk on Sondheim’s intelligence and what is ultimately a mixed but occasionally rousing revue, but a hangover occurs for those with a discerning eye.

The 1987 debut in London had additional numbers and a re-worked book, yet CST opted with the original version, but adding an intermission. Both versions still contain the same structural problems, however, and it would take a genius of Jerome Robbins-esque proportion to fix the inherent predicaments, a particularly thorny peril when theatrical auteurs (scant to be found in the modern musical landscape, anyway) may reinterpret a revival, but are powerless when it comes to rewriting it.

Goldman’s libretto (“virtually plotless” according to Sondheim) takes us to a soon-to-be demolished theatre that was once home to the fictional Weismann’s Follies. Weismann himself throws a reunion party and a geriatric ward of antiquated thespians show up (alongside their ghostly younger selves) to belt out a song and belt down a drink.

The break in these routines comes in the form of two middle-aged couples: Buddy and Sally (a philandering traveling salesman and his mousy, delusional housewife) and Ben and Phyllis (a cold-hearted, distant politician and his drolly cynical socialite wife). The conflict is that Sally has been besotted with Ben for decades, Buddy is in love with Sally but beds a woman elsewhere, Phyllis and Ben play at marriage but there is no love between them, and Ben is in love with Ben. They, too, coexist with the ghosts of their younger selves, but these ex-showgirls and their Stage Door Johnnies are largely unsympathetic principles. In fact, if these two couples were surreptitiously dropped into Company, no one would notice.

The break in these routines comes in the form of two middle-aged couples: Buddy and Sally (a philandering traveling salesman and his mousy, delusional housewife) and Ben and Phyllis (a cold-hearted, distant politician and his drolly cynical socialite wife). The conflict is that Sally has been besotted with Ben for decades, Buddy is in love with Sally but beds a woman elsewhere, Phyllis and Ben play at marriage but there is no love between them, and Ben is in love with Ben. They, too, coexist with the ghosts of their younger selves, but these ex-showgirls and their Stage Door Johnnies are largely unsympathetic principles. In fact, if these two couples were surreptitiously dropped into Company, no one would notice.

Sondheim’s score, which is shackled to this conceit, is pioneering, ingenious, and strikingly dramatic with some of the most stunning lyrics ever written (“Beauty Celestial, the Best You’ll Agree”). His pastiches of famous songsmiths from the 1920s and ’˜30s are consummately successful in that they call to mind Gershwin and Berlin while never being campy or letting us forget that a modern Boy Wonder (at the time) is on display. In fact, Sondheim is the reason why this show is ever revived, although it continually receives mixed reviews, including the current production at the behemoth Marriott Marquis on Broadway.

For some (and I strongly suspect this will be true for the CST production), patchy production values and a bewildering book are forgotten once Sondheim’s tuneful takeoffs are trumpeted – we no longer care that we don’t care about the four leads. (A quote from Martin Gottfried sums up why critics tend to overpraise Follies and bury its problems in a final paragraph: “Every other musical should have its faults.”)

Yet the book of Follies is a huge fault. One would think that a scaled-down production, such as the one here at CST, might make the show emotionally resonant, but when one lead is an unemotional actor and another is far too young for his role, when the choreography and direction vacillate between brilliant and uninspired, and when we are in the wrong setting, the book’s faults are highlighted even more.

Yet the book of Follies is a huge fault. One would think that a scaled-down production, such as the one here at CST, might make the show emotionally resonant, but when one lead is an unemotional actor and another is far too young for his role, when the choreography and direction vacillate between brilliant and uninspired, and when we are in the wrong setting, the book’s faults are highlighted even more.

To loosely paraphrase Walter Kerr’s Times review from 40 years ago, this mammoth and murky entertainment has nothing in mind but to watch these four vexed leads drift in and out among the other guests in groping search of one another, stating (and restating in song) the current temperatures of their lives, ending in “Loveland,” where each main character exorcises their regrets in a mini-version of a full-fledged Follies show.

The fact that the real musical pastiches do not have any real relationship to the marital squabbles at hand makes this show ultimately incohesive and disjointed: the reminiscences of the past do not effectively fuse with the contemporary, cross-hatched love stories. The authenticity of these troubled marriages (which ought to give the evening its solid traction) is skimpy and, thus, even with some of the best songwriting in musical theatre history, there is a monotony that keeps us emotionally distant. “Loveland,” the final five numbers of the show where each lead acts out their own folly (Follies-style), has always been the highlight of all four productions this reviewer has seen, including CST, but it left me with a temporary high that was soon put in check by what came before.

Follies needs a laundry list of talent to become a satisfying evening: a director with a unique vision and style who can tap into the minimal psychology of the piece while conjuring up bittersweet nostalgia; a choreographer who can incorporate character into dances that are freshly original while paying homage to old-style showmanship; triple-threat actors with distinctive personalities who can make each Sondheim song soar while matching the age of their characters and having us believe that they were once the brightest talent on The Great White Way; a beefy orchestra that can handle Jonathan Tunick’s brilliant orchestrations; and a set designer who can turn a modern theatre into a haunted, decrepit world that was once a glamorous showplace.

It can’t be done.

Even the original production, which apparently did have all of the aforementioned ingredients, ultimately could not find an audience. Musical Theatre historian Steven Suskin knows why: Follies, with its exciting score and inarguably memorable trappings, was a show that merited repeat visits – but because it was overproduced, overghosted, and overwritten, it was awfully hard to get through the first time.

Chicago Shakespeare’s production is underproduced and underghosted, but still overwritten. This is exactly the kind of production we would get from Encores in New York or Reprise in Los Angeles: we are thrilled to witness shows receive professional attention, even as we understand why they are rarely produced.

The characters in Follies come to a party for nostalgia, but are hit in the face with regret and broken dreams. Modern audiences are flocking to shows that are nostalgic (jukebox musicals, revivals, movie translations) so that they don’t have to face our tough times. This is why, I suspect, very few people will say out loud that CST’s production is simply a mixed bag.

For starters, this is the wrong theatre for Follies: the modern thrust in this beautiful house means that there isn’t a bad seat to be had, but Weismann’s cavalcades would have taken place on a proscenium stage. Plus, the slimmed down orchestra of 12 looms behind the playing area on multi-tiered platforms, when there needs to be a tiny combo band in view and a hidden orchestra. I deduce that we are to believe this tiny orchestra is the kind Weismann would have hired for his soiree, but would he have constructed those platforms for the musicians to comfortably see each other?

For starters, this is the wrong theatre for Follies: the modern thrust in this beautiful house means that there isn’t a bad seat to be had, but Weismann’s cavalcades would have taken place on a proscenium stage. Plus, the slimmed down orchestra of 12 looms behind the playing area on multi-tiered platforms, when there needs to be a tiny combo band in view and a hidden orchestra. I deduce that we are to believe this tiny orchestra is the kind Weismann would have hired for his soiree, but would he have constructed those platforms for the musicians to comfortably see each other?

The orchestral reductions by David Siegel are admirable, but they’re a bit brassy and capture neither the small combo feel nor the grand sound of theatre past – emphasizing the discrepancy between the modern and the memories in Goldman’s script. The musical direction by Brad Haak is magnificent, overshadowed only by the sharp and powerful conductor and pianist Valerie Maze. Unfortunately, so mesmerizing was Maze’s leadership and proficiency that my eyes often wandered to watch her direction (one audience member commented that Maze was a highlight – to which I concur).

Scenic designer Kevin Depinet was clearly limited by director Gary Griffin’s vision of the show (or lack thereof). Some hanging ropes, scattered light poles and a skewed catwalk do not read as a Grand Dame theatre of majesty turned porno palace. In a cacophonous moment when the lead couples argue amongst their ghosts, the theatre must erupt from a sickly auditorium into The Follies of old for “Loveland;” instead, some pretty curtains are flown in just in front of the orchestra, leaving the huge playing area as empty as it was from the beginning: all we have are three steps which are maddeningly used for actors to sit upon with no motivation whatsoever.

The sound design by Joshua Horvath and Ray Nardelli is the apotheosis of technical stagecraft: balancing 28 players with 12 musicians is a daunting task, but these aural magicians brought clarity to the proceedings that are a nonpareil of sonority. Virgil C. Johnson’s costumes are by and large stupendous, but it is in the mimicking of old-school Ziegfeld extravaganzas in “Loveland” that Johnson soars: in particular, the shimmering coffee-colored gown for Sally in “Losing My Mind.”

Worldwide entertainer Caroline O’Connor chews up Phyllis’ dialogue and spits it out with glee. Between her idiosyncratic voice and superlative movement, the “Lucie and Jessie” number (backed by dancers Julius C. Carter and Rhett Guter) was hot, hot, hot! Brent Barrett plays Ben with the aloofness one would expect from a jaded politician, and his distinguishing, succulent tenor vocals are as gorgeous as ever, but it’s a surface performance that barely hints at Ben’s demons of regret and disenchantment (Barrett’s normal slickness was perfect for Billy Flynn in Chicago).

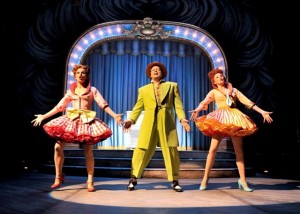

Worldwide entertainer Caroline O’Connor chews up Phyllis’ dialogue and spits it out with glee. Between her idiosyncratic voice and superlative movement, the “Lucie and Jessie” number (backed by dancers Julius C. Carter and Rhett Guter) was hot, hot, hot! Brent Barrett plays Ben with the aloofness one would expect from a jaded politician, and his distinguishing, succulent tenor vocals are as gorgeous as ever, but it’s a surface performance that barely hints at Ben’s demons of regret and disenchantment (Barrett’s normal slickness was perfect for Billy Flynn in Chicago).

Susan Moniz suits the unfulfilled housewife Sally perfectly; it’s a pleasure to watch her slipping down the drain, but strangely enough, she kept her threadbare sanity in check during her “Losing My Mind” number. It is Robert Petkoff as Buddy that seems to be the odd-man out in this dysfunctional quartet; certainly affable and oozing with talent, he is far too young for Buddy. Also, this role requires some serious acrobatic dancing and Petkoff is not that dancer. Still, the hard-working actor managed to hold his own in “Buddy’s Blues,” a high-paced Vaudeville number that would leave a marathon runner winded.

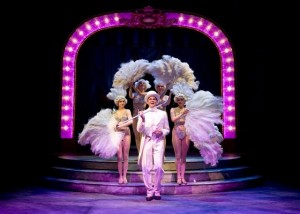

What made this Follies rapturous at times were the actors who simply had an air of theatricality about them. Mike Nussbaum, in particular, had such a commanding presence as Weismann that one could easily accept he had once led the finest company in New York. When Bill Chamberlain belted out “Beautiful Girls,” his regal stance and proud face made evident Roscoe’s indifference to age: to us, he was and still is the best Follies singer ever.

The montage of pastiches (or, as Sondheim calls them, fond imitations) from olden days could not have been more fun: Dennis Kelly and Ami Silvestre were adorable as the Whitmans (“Rain on the Roof”); buxom and coquettish Kathy Taylor had a ball (“Ah, Paris!”) and Marilynn Bogetich, complete in orthopedic shoes, made us giddy (“Broadway Baby”).

Alex Sanchez’ choreography was one hit-and-miss element that kept the evening bouncing between stimulating and shoulder-shrugging: Sanchez really showed off his clever movements in “Who’s That Woman”, where Carlotta (Hollis Resnik) and other elder hoofers (and their chorine doppelgangers) tapped their way to tumultuous ovations – what was missing was the mistakes: are you telling me that women who traded in their toe-shoes long ago remember their choreography verbatim?; “You’re Gonna Love Tomorrow” has always been a creative highlight in Follies, but here it felt unimaginative; and while his “Lucy and Jessie” was the best number of the night, it owed its style to Bob Fosse (as did the fan dancing in “Live, Love, Laugh” – very Chicago).

Alex Sanchez’ choreography was one hit-and-miss element that kept the evening bouncing between stimulating and shoulder-shrugging: Sanchez really showed off his clever movements in “Who’s That Woman”, where Carlotta (Hollis Resnik) and other elder hoofers (and their chorine doppelgangers) tapped their way to tumultuous ovations – what was missing was the mistakes: are you telling me that women who traded in their toe-shoes long ago remember their choreography verbatim?; “You’re Gonna Love Tomorrow” has always been a creative highlight in Follies, but here it felt unimaginative; and while his “Lucy and Jessie” was the best number of the night, it owed its style to Bob Fosse (as did the fan dancing in “Live, Love, Laugh” – very Chicago).

Director Griffin, a deservedly well-loved staple of Chicago theatre, created an intimate revival of what many assume should be a hugely produced spectacle. While his commendable production had astounding moments of glory, the possible emotional punch of the show was not present and it never felt like a haunted theatre. Perhaps the real ghost on display is this musical itself: one that haunts the world in revival after revival searching for the book it never knew.

Director Griffin, a deservedly well-loved staple of Chicago theatre, created an intimate revival of what many assume should be a hugely produced spectacle. While his commendable production had astounding moments of glory, the possible emotional punch of the show was not present and it never felt like a haunted theatre. Perhaps the real ghost on display is this musical itself: one that haunts the world in revival after revival searching for the book it never knew.

photos by Liz Lauren

Follies

Chicago Shakespeare Theater

scheduled to end on November 13

for tickets, visit http://www.chicagoshakes.com

for info on this and other Chicago Theater, visit http://www.TheatreinChicago.com