TENNESSEE W’S MASTER CLASS FOR ACTORS

The New American Theatre production of Five Beauties (or, as it turned out to be at the performance I attended, Four Beauties) is not like going to the theater at all: it’s like attending an acting class in which each scene is beautifully executed and is unified by the fact that the author of each playlet is Tennessee Williams. Writing this well clearly inspires and brings out the best in good actors. The bare-bones production, with its minimal set pieces and props, does not pretend to be anything else but an acting class, and it is all the more an honest piece of theater for being so straightforward in the demands it makes on an audience. What it achieves is to remind us yet again that Williams is the American theater’s greatest poet and its most humane and compassionate chronicler of the messes most people get into.

The revelation here is “The Traveling Companion” (written by Williams in 1970 and largely unknown), which is no more than an anecdote writ large about an encounter between an aging writer, clearly based on Williams himself, and a hustler who has agreed to accommodate the writer until he sees that there is only one bed in the hotel room that they are checking into. The play provides conclusive proof that Williams could still write brilliantly during the period often described as a time in which the great playwright was in decline. His observations of what transpires between these two lonely and desperately needy men are sharp and bruising and ultimately tender. Williams takes no sides; he is all too aware of each man’s flaws and finds, despite their tawdry stories, the dignity that men tap into, even when they seem to be left with no dignity at all. Tom Groenwald is too young for Vieux, the aging author, but be locates something profoundly real in his behavior, and his interplay with Byron Field’s inchoate but oddly sensitive Beau is rich in detail.

The revelation here is “The Traveling Companion” (written by Williams in 1970 and largely unknown), which is no more than an anecdote writ large about an encounter between an aging writer, clearly based on Williams himself, and a hustler who has agreed to accommodate the writer until he sees that there is only one bed in the hotel room that they are checking into. The play provides conclusive proof that Williams could still write brilliantly during the period often described as a time in which the great playwright was in decline. His observations of what transpires between these two lonely and desperately needy men are sharp and bruising and ultimately tender. Williams takes no sides; he is all too aware of each man’s flaws and finds, despite their tawdry stories, the dignity that men tap into, even when they seem to be left with no dignity at all. Tom Groenwald is too young for Vieux, the aging author, but be locates something profoundly real in his behavior, and his interplay with Byron Field’s inchoate but oddly sensitive Beau is rich in detail.

“Auto-Da-Fé,” a concentrated portrait of a neurotic young man (the highly wired and electric Anthony Cran) and a mother whose good sense and practicality and surface calm serve to hide a monster within (a terrific Bibi Tinsley), is perhaps the most tightly-wound of the evening’s short pieces and moves towards its climax with frightening speed and is the play in which the two actors seem most deeply connected; watching the actors play out this painfully accurate character study is like being present at a tennis match, in which it’s not a ball we are watching go back and forth but rather the alternately tragic and comic volley – as old as time, yet so freshly observed – between mother and son.

“Auto-Da-Fé,” a concentrated portrait of a neurotic young man (the highly wired and electric Anthony Cran) and a mother whose good sense and practicality and surface calm serve to hide a monster within (a terrific Bibi Tinsley), is perhaps the most tightly-wound of the evening’s short pieces and moves towards its climax with frightening speed and is the play in which the two actors seem most deeply connected; watching the actors play out this painfully accurate character study is like being present at a tennis match, in which it’s not a ball we are watching go back and forth but rather the alternately tragic and comic volley – as old as time, yet so freshly observed – between mother and son.

“Moony’s Kid Don’t Cry” is the least characteristic of that special voice which is Williams’s own, having been written as early as 1934 and influenced, perhaps, by the work of Clifford Odets, a playwright we don’t often think of when we think of Williams; but its power is unmistakable and it provides Scott Sheldon the opportunity to seize the part and run with it. Sheldon doesn’t seem to be acting at all; he seems to be living inside Moony’s skin, poetry emanating from him as if that is the way he speaks. Jade Sealey, as his bored and all-too-realistic wife, is a splendid foil, her body drained of life and her eyes closed to the encroaching darkness around her. At first, they don’t seem to be acting in the same play, but ultimately they are palpably defined by their differences.

“Moony’s Kid Don’t Cry” is the least characteristic of that special voice which is Williams’s own, having been written as early as 1934 and influenced, perhaps, by the work of Clifford Odets, a playwright we don’t often think of when we think of Williams; but its power is unmistakable and it provides Scott Sheldon the opportunity to seize the part and run with it. Sheldon doesn’t seem to be acting at all; he seems to be living inside Moony’s skin, poetry emanating from him as if that is the way he speaks. Jade Sealey, as his bored and all-too-realistic wife, is a splendid foil, her body drained of life and her eyes closed to the encroaching darkness around her. At first, they don’t seem to be acting in the same play, but ultimately they are palpably defined by their differences.

The last and least of the evening’s plays is “The Lady of Larkspur Lotion,” a five-finger exercise that anticipates both A Streetcar Named Desire and Vieux Carré; in it, Mona Lee Wylde’s hard-edged landlady of a New Orleans flea-bag hotel finds rhythms and cadences that are pure Williams, and John Copeland’s alcoholic writer gives voice to what may be the clearest declaration of Williams’s own philosophy, a hymn to the disenfranchised and the dreamers he stood up for when the rest of the world disowned them (and how fascinating to hear the name this boozehound gives himself).

The last and least of the evening’s plays is “The Lady of Larkspur Lotion,” a five-finger exercise that anticipates both A Streetcar Named Desire and Vieux Carré; in it, Mona Lee Wylde’s hard-edged landlady of a New Orleans flea-bag hotel finds rhythms and cadences that are pure Williams, and John Copeland’s alcoholic writer gives voice to what may be the clearest declaration of Williams’s own philosophy, a hymn to the disenfranchised and the dreamers he stood up for when the rest of the world disowned them (and how fascinating to hear the name this boozehound gives himself).  Unfortunately, as the character who will ultimately become, in a later play, the more beautifully calibrated Blanche DuBois, Cameron Meyer doesn’t begin to flesh out with any psychological subtlety this creature with a feverish fear of cockroaches. It was hard to tell whether her incessant trembling was character work or just a moment of bothersome stage fright.

Unfortunately, as the character who will ultimately become, in a later play, the more beautifully calibrated Blanche DuBois, Cameron Meyer doesn’t begin to flesh out with any psychological subtlety this creature with a feverish fear of cockroaches. It was hard to tell whether her incessant trembling was character work or just a moment of bothersome stage fright.

The directors of these pieces mostly keep out of the way of the actors – which is good – but Jack Stehlin deserves mention for the drive he brings to “Auto-Da-Fé.”

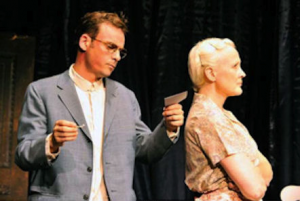

[Editor’s note: the fifth and regretfully unseen beauty of the evening was called “Green Eyes,” pictured right]

[Editor’s note: the fifth and regretfully unseen beauty of the evening was called “Green Eyes,” pictured right]

photos by Daniel G. Lam

Five Beauties

The New American Theatre in Los Angeles

extended to November 20

for tickets, visit http://newamericantheatre.com/fivebeauties.html