THE ART OF MAKING ART

In economically troubled times such as these, many artistic directors are vainly attempting to figure out how their output can be remunerative. Instead of presenting a bold concept to audiences, artistic directors (and many other disciplinary artists) seem to be relying on proven methods of the past in order to find an audience. In doing so, they demote their imagination and downgrade their perspicacity, perpetuating what some see as a cultural dark age. These leaders of stagecraft, whether with dance or drama, rely on both familiarity (in order to please season subscribers) and inexpensive productions (in order to please their Board of Directors).

With such a dearth of risk-taking visionaries in the arts, this is a dispiriting age for this critic. But a new documentary by filmmaker Bob Hercules has diminished my sense of hopelessness, for nothing stirs my soul and fuels my optimism more than a great tale about visionary American artists who not only transformed their art form, but found an audience for it as well. Joffrey: Mavericks of American Dance, a heartfelt history of the Joffrey Ballet, may be a sentimental love letter to founders Robert Joffrey and Gerald Arpino, but it imbued me with a passion and inspiration the likes of which I have not felt in some time.

While Hercules’ chronology is not an attempt to reinvent the documentary form, the writer/director saturates his compelling film with the same professionalism, dedication, and love that his subject matter gave to the world of ballet. Seamlessly blending insightful interviews with archival photos and film (astounding research by Julie Johnson), Hercules commendably creates a film where the story is the thing, and the story of the Joffrey Ballet – a thrilling, touching and turbulent account – must be seen.

While Hercules’ chronology is not an attempt to reinvent the documentary form, the writer/director saturates his compelling film with the same professionalism, dedication, and love that his subject matter gave to the world of ballet. Seamlessly blending insightful interviews with archival photos and film (astounding research by Julie Johnson), Hercules commendably creates a film where the story is the thing, and the story of the Joffrey Ballet – a thrilling, touching and turbulent account – must be seen.

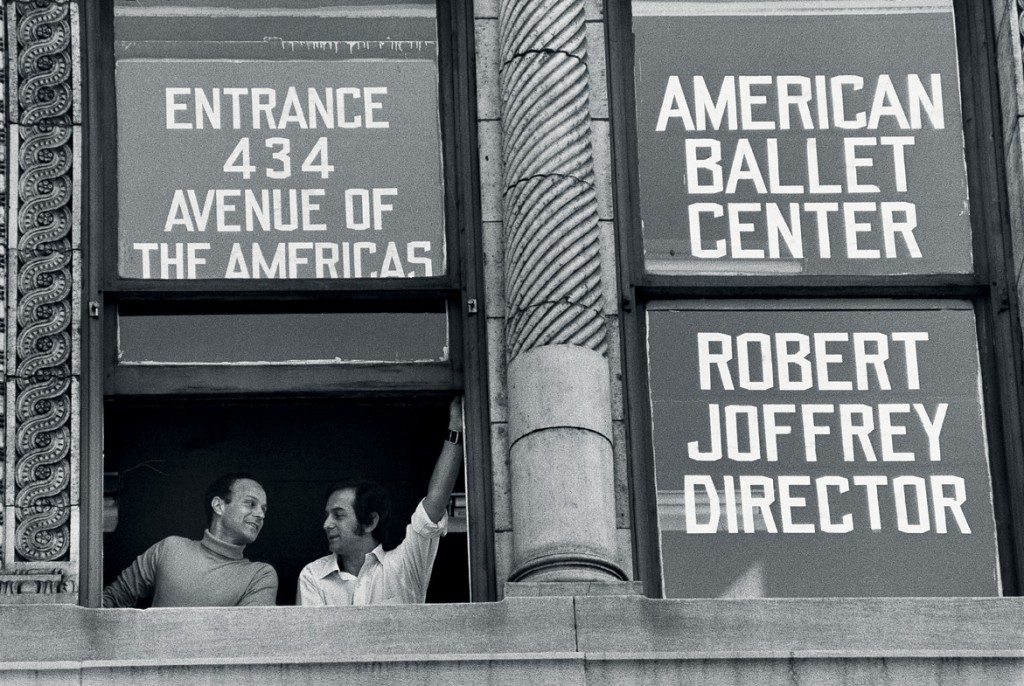

Robert Joffrey knew at an early age that he wanted to be a ballet impresario, so he diligently applied himself and, along with fellow dancer and choreographer Gerald Arpino, opened up the Joffrey Ballet School in 1953 and the Joffrey Ballet in 1956. From the beginning, Joffrey insisted that his dancers master the classical techniques, which in turn would nourish all other dance styles. It is this pioneering innovation that revolutionized dance in America.

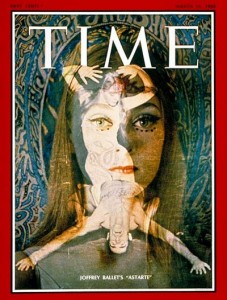

Once the ballet company was established at home and abroad, benefactor Rebekah Harkness, who had been funding Joffrey, absconded with his company and its members (renaming it the Harkness Ballet). While this was a devastating blow, Joffrey eventually regenerated his company from nothing and used the turbulent ’˜60’s as inspiration for the groundbreaking ballet Astarte (1967), which landed the company on the cover of Time Magazine.

Once the ballet company was established at home and abroad, benefactor Rebekah Harkness, who had been funding Joffrey, absconded with his company and its members (renaming it the Harkness Ballet). While this was a devastating blow, Joffrey eventually regenerated his company from nothing and used the turbulent ’˜60’s as inspiration for the groundbreaking ballet Astarte (1967), which landed the company on the cover of Time Magazine.

It is an event which is reminiscent of the famous story of another artistic American visionary: Walt Disney, who, after losing his animators and his character Oswald the Lucky Rabbit to an unscrupulous distributor, created Mickey Mouse. It is this gung-ho spirit that is celebrated in Mavericks, even as Hercules wisely includes the truth that the Joffrey Ballet has, at times, veered from its mission with cash-cow ballets such as Billboards (1993), which critic Hedy Weiss calls “kitschy.” (The Nutcracker has been an annual mother lode for the company since 1987, but Robert Joffrey’s final personal production barely receives mention in the film.)

Occasionally, it would have served Mavericks to supplement some parts of the story, narrated by the gloriously subdued Mandy Patinkin. Since Harkness figures so prominently in the story, the viewer will be chomping at the bit to find out what happened to her company and if she received her comeuppance. When we hear that Joffrey and Arpino “formed a partnership that would last a lifetime,” the uninitiated will have no idea that they were lovers until much later when it is mentioned that “although they were no longer lovers, they lived together for the rest of their lives.” When an interviewee states that “they called each other cousins, but everyone knew that they weren’t,” the viewer should be given insight as to what it was like to be closeted in an occupation populated by a preponderance of gay men.

Also skirted over was the devastation wreaked upon the dance world by AIDS, even as we learn that Joffrey’s death to the disease in 1987 was obfuscated as liver problems by the media. All we hear is, “many dancers from the Joffrey Ballet had died earlier.” A seminal era such as this demands a more thorough examination.

Nonetheless, the film is entirely engrossing as the company affects and is affected by over a half century of American history. In particular, the remembrance of Kennedy’s assassination while the company was in Moscow is enormously wistful; and Joffrey’s untimely death is evocatively and palpably painful.

Mark Bandy’s original music – tinged with classicism – is driving and touching. The incredible fade work and editing of Melissa Sterne is flawless and inventive. Directors of photography Michael Swanson and Keith Walker do some sharp work, even as the footage of interviews vacillates from elegant to unimaginative.

When Joffrey succumbed to AIDS, Arpino became the beacon who guided the Joffrey Ballet from 1988 until 2007. While Joffrey may be a household name, Arpino is not. Yet this choreographer was an enormous inspiration to the dance world. Maia Wilkins, a former Joffrey dancer, states in the movie that Arpino influenced her to realize that all art is about using one’s technique as a medium for expression. Hence, art is a means to view and reflect upon our world, to escape to some other place, to look at your life, and to bring on new perspectives. The artful Joffrey: Mavericks of American Dance did these same things for me.

photos courtesy of Joffrey Ballet

Joffrey: Mavericks of American Dance

opened on January 27, 2012

released on DVD June 12, 2012

1 disc | 82 minutes | no rating

to order, visit Amazon