THE FEATS OF THE FOOTES

America is preoccupied with an unstable economy, tax increases, oil profiteering, cash deficiencies, and the plummeting worth of real estate. Yet history does indeed repeat itself, for these were the same issues facing Americans in the Reagan years, and Dividing the Estate, which takes place in 1987 Texas, will reverberate with familiarity to modern audiences. Horton Foote’s entertainingly mild 1989 drawing room comedy isn’t particularly insightful or ambitious, but it has an appealing, Chekhovian nature that wins us over with its all-too-human characters and diverting commentary about a world that is slipping away.

Classic themes of materialism, alcoholism, and classism abound when full-blooded Southern matriarch Stella (Elizabeth Ashley) has her three children over for dinner. The oldest is widowed Lucille (Penny Fuller), who lives with Stella on her plantation-like estate. Lucille helps out with household duties while her son (Devon Abner) handles Stella’s affairs (in typical Foote fashion, the son is named Son).

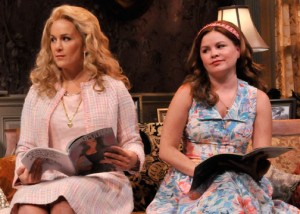

It’s easy to see how the 1980s gave birth to slackers, as Lucille’s two younger siblings epitomize those who are wholly dependent on the family fortune: Gambling womanizer Lewis (Horton Foote, Jr.) keeps drunkenly asking for advances in his allowance while Mary Jo (Hallie Foote) complains that her share of the loot isn’t nearly enough to support her materialistic lifestyle, and that of her husband Bob (James DeMarse) and their two pampered daughters, Emily (Jenny Dare Paulin) and Sissie (Nicole Lowrance).

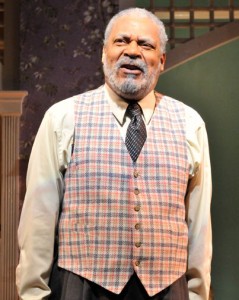

It is before and during dinner that the banter crumbles into a combative discourse between the avaricious siblings and the implacable matron. No one, it seems, is willing to give up the lifestyle to which they have become accustomed. This includes the 92 year-old African-American servant Doug (Roger Robinson) who refuses to stop serving dinner even though he has violent shakes. Above all, Stella is unwilling to discuss either how the estate will be divided or the possibility of oil-leasing on her land. Without revealing details, suffice to say that an unexpected occurrence puts the quarrelling on hold, but later bolsters the children’s demands to divide the estate.

This slight but amusing play’”essentially plot-free’”will especially resonate with those who come from a Southern background. The characters retain graciousness even as they take delicious turns rubbernecking at each other’s lives and deliberating over lineage and its inherent mythology. Other spectators will wish that the dialogue had tastier morsels of venomous, Hellman-esque Southern behavior or the cancerous secrets of Tennessee Williams’ gothic families. But Horton Foote wrote with gentility, a charming politeness reserved for gentlemen and ladies (“yes ma’am” simply teems in his works), so you will see no August: Osage County-like in-your-face, dysfunctional fireworks going on here.

The proceedings feel both antiquated and somehow familiar, and since the story lacks impetus, there is a threat of boredom hanging on the script like Spanish Moss. The laughs are mainly mild because what appears to be a black comedy on the surface lacks the gallows humor necessary for true guffaws, even as the dominant theme is death itself. (Also, some of the acting seemed inconsequential and lacked spice.) Thankfully, director Michael Wilson and a few of the actors liven up the gentility by creating distinctive characters out of ones that don’t seem particularly remarkable on paper.

The standouts are Ms. Foote, who brings rib-tickling physical antics to the whiny and demanding daughter Mary Jo, and Mr. DeMarse, who adroitly vacillates from an agreeable hangdog husband to pushy interloper son-in-law Bob. It is Mr. Robinson who truly steals the show as the servant Doug as he trembles with pride when he sees his world coming to an end.

The standouts are Ms. Foote, who brings rib-tickling physical antics to the whiny and demanding daughter Mary Jo, and Mr. DeMarse, who adroitly vacillates from an agreeable hangdog husband to pushy interloper son-in-law Bob. It is Mr. Robinson who truly steals the show as the servant Doug as he trembles with pride when he sees his world coming to an end.

Although Dividing the Estate was first produced in 1989, this is being billed as Horton Foote’s final play. This is because the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright re-tooled the script for an off-Broadway production, which ran for a month in 2007. That production, which moved to Broadway and closed after a two month run, ended in 2009, exactly two months before Mr. Foote’s death at the age of 93. The show now playing at the Old Globe is the Broadway transplant, with much of the original cast and design team intact. Included in the transfer is the luminous Ms. Ashley, who is repeating her role of Stella; she may be a bit too youthful for the part, but she certainly has the flavor of a Southern matriarch (her interpretations in Williams’ plays are legendary). Also on board from New York are the brilliant lighting by Rui Rita, which shifts in tone and hue as the evening progresses, and the magnificent, plush set of Jeff Cowie.

I can’t call the show exciting. Indeed, it seems clear why it took 20 years for this play to hit Broadway, and why it did not have a long run’”it’s almost too subdued and old-fashioned’”but it contains all of the elements that made Foote a classic American playwright. Best-evidenced in his magnificent The Trip to Bountiful, Foote brought decorum to the stage, along with a wistful understanding of a vanishing world, the bittersweet yearning of memory, a twinkling empathy for his fellow man, and, above all, a gracious humor that accompanied his keen understanding of human nature. The reasons to see Dividing the Estate are the qualities of Horton Foote himself.

I can’t call the show exciting. Indeed, it seems clear why it took 20 years for this play to hit Broadway, and why it did not have a long run’”it’s almost too subdued and old-fashioned’”but it contains all of the elements that made Foote a classic American playwright. Best-evidenced in his magnificent The Trip to Bountiful, Foote brought decorum to the stage, along with a wistful understanding of a vanishing world, the bittersweet yearning of memory, a twinkling empathy for his fellow man, and, above all, a gracious humor that accompanied his keen understanding of human nature. The reasons to see Dividing the Estate are the qualities of Horton Foote himself.

photos by Henry DiRocco

Dividing the Estate

Old Globe Theatre in San Diego

scheduled to end on February 12, 2012

for tickets, visit http://www.theoldglobe.org