ORIGINAL SIN

In their fevered exploration of the seven deadly sins, Figure 8 playwright/co-director Phinneas Kiyomura and co-director Jerry Kernion seem hell bent on making sin seem as original as possible. Visually, their approach results in moments of genuine power. Emotionally, it has its limits.

Kiyomura rather enigmatically calls Figure 8 a collection of eight plays, rather than one play with eight scenes. It might make sense to regard them as separate entities if only they shared a thematic interest in sin, but the characters, some of whom appear in multiple plays, end up interlacing in genuinely inventive and satisfying ways, so this does feel like a single work.

The program and the press materials are full of Kiyomura’s and Kernion’s philosophical and metaphorical inspirations. It makes for very interesting reading, and they seem like smart, passionate guys—but what is on stage doesn’t always match their stated intentions. The creators aim for something cerebral, ethereal even, but too often scenes devolve into loud, rather course spectacle. The subject matter includes a teacher on cocaine posing for the cover of an educational magazine; a deaf woman desperately demanding love and affection from her addict boyfriend; and a conservative city worker’s lesbianism emerging when she becomes obsessed with a tawdry coworker.

Kiyomura is fascinated by what happens in the working class cities that surround Los Angeles, and he sets the plays in Burbank, Fullerton, Downey, La Mirada, Glendale, maybe Anaheim, and possibly Hollywood—though Hollywood seems not to fit the workaday theme. There is nothing in the material to help anchor us specifically in any of these cities, nor are the locations printed in the program. Plus, the plays are titled in lower case with maddening opacity (waiting, the rational mind, good souls, among others) making it difficult to delineate which play happened in what order, let alone where they took place.

Kiyomura is fascinated by what happens in the working class cities that surround Los Angeles, and he sets the plays in Burbank, Fullerton, Downey, La Mirada, Glendale, maybe Anaheim, and possibly Hollywood—though Hollywood seems not to fit the workaday theme. There is nothing in the material to help anchor us specifically in any of these cities, nor are the locations printed in the program. Plus, the plays are titled in lower case with maddening opacity (waiting, the rational mind, good souls, among others) making it difficult to delineate which play happened in what order, let alone where they took place.

Maybe the playwright leaves no telltale clues because he believes such geographical (not to mention chronological) distinctions are meaningless, but this gives the impression that he regards these cities as interchangeable since they are not Los Angeles—but given some of what he writes in the program, this is likely not the case. He talks of these communities almost as individual characters with quirky reactions to their glamorous neighbor. That’s an interesting idea which remains unexplored on stage.

In this tricky material, the actors are asked to make huge emotional transitions in hairpin turns. There are four actors who elevate and expertly navigate the zigzags of the material, which, when it works, can be thrilling. There is a startling tenderness to Darrett Sanders’ religiously observant janitor who possibly succumbs to a potentially savage walk on the wild side. Karl Herlinger is strangely appealing as an incestuously inclined brother who waits with his sister in a hospital for their elderly father to die (is it possible to actually hope he gets the girl—even when that girl is his sister?).

In this tricky material, the actors are asked to make huge emotional transitions in hairpin turns. There are four actors who elevate and expertly navigate the zigzags of the material, which, when it works, can be thrilling. There is a startling tenderness to Darrett Sanders’ religiously observant janitor who possibly succumbs to a potentially savage walk on the wild side. Karl Herlinger is strangely appealing as an incestuously inclined brother who waits with his sister in a hospital for their elderly father to die (is it possible to actually hope he gets the girl—even when that girl is his sister?).

Kirsten Vangsness is a plus-sized porn star having sex with a stranger, which her Russian boyfriend captures on video. Brad C. Light’s Russian porn maven not only has a dead-on accent, but he is quicksilver in emotion – funny and volatile, then, suddenly, softly, a note of sadness appears, giving unexpected depth and urgency to his work.

Vangsness is particularly effective. She plays the porn actress in three of the plays, first teasing the janitor in one before copping off with his dimwitted assistant, then the video scene, and finally, as the unlikely object of obsession for a seemingly straight woman. Vangsness is lightning quick and absolutely fearless. She effortlessly maneuvers her way through comedy, frightening violence, and sexual physicality that is as unforced and real as it is graphically matter of fact.

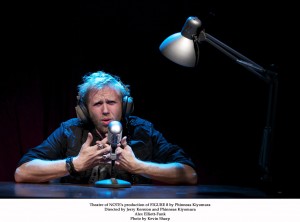

Some of the other actors let the material down. As a druggie rock star contemplating suicide, Alex Elliott-Funk struggles with the explosive beats the text demands. He cannot find a way to believably express the depths required; nor does he effectively seem as drug-addled as he needs to be.

In a double role, Justin Brinsfield is natural and funny as the janitor’s flunky, but he falters as a violent, sadistic minister who punishes a parishioner for resenting a paralyzed spouse. Brinsfield is seemingly so afraid of overacting that he flattens the whole performance. The rest of the cast has moments of undeniable connection and force, but being relevant to the proceedings is one thing, finding transcendence is quite different—and much more difficult to accomplish.

The staging is imaginative, and Davis Campbell’s set, David Chitwood’s graphics, Bryan Maier’s sound and video, and Matt Richter’s lighting are uniformly excellent, seamlessly working together to take us in and out of different settings and realities with wit and skill.

While Kiyomura’s and Kernion’s intentions are fully-realized by the design team, they now need to solve the enigmatic narrative of Figure 8. Kiyomura has many good ideas and he is obviously gifted and offers up some truly electrifying moments. But he hasn’t connected those ideas in a way that feels grounded or that completely makes sense. He and Kernion go for broke, over and over, hitting us with dramatic incident while neglecting to give us an overall compelling drama.

photos by Kevin Sharp

Figure 8

Theatre of NOTE in Hollywood (Los Angeles Theater)

scheduled to end on April 1, 2012

for tickets, visit http://www.theatreofnote.com