MEMORIES OF SEAGULLS PAST

If you have never seen The Seagull – though I can’t imagine a seasoned theatergoer who hasn’t, can you? – you just might possibly get an inkling of what Anton Chekhov’s masterpiece should be in the Antaeus Company’s otherwise listless and tone-deaf production, which stubbornly refuses to illuminate the quirkiness of human behavior as defined by Chekhov.

The problem here is that this reviewer has probably seen more productions of The Seagull than any other play, and, clearly, some of those productions have altered forever the way one sees the play or some of the ways one has come to understand the nature of its endlessly fascinating inhabitants. A multitude of possibilities exist, many already explored, many open to new exploration. And therein lies the reason for doing the play again and again. No matter how often you revive plays like Noises Off or Arsenic and Old Lace or You Can’t Take It With You, the amount of fun you have will probably depend on the actors, but the plays will remain the same. But the genuine classics come freshly alive through each new interpretation. That is, indeed, if the pattern is to breathe new life into it.

The Seagull is a tragicomedy of unrequited love, in which Medvedenko loves Masha who loves Konstantin who loves Nina who falls in love with Trigorin who is the lover of Arkadina, who is Konstantin’s mother. And what separates it from soap opera are the conflicts that arise from the raw emotions these romantic aberrations create. Konstantin is a writer seeking new forms; his rival, Trigorin, is a commercially successful hack convinced that his epitaph will declare that, good a writer though he may be, he is no Tolstoy. Konstantin’s mother is a renowned actress, who imagines herself a Duse but who, in all probability, is closer in style to Bernhardt. Nina wants to be a more modern actress. In this narrative, old forms are fighting against being replaced by new forms. The play also puts into bas-relief an entire social structure and the upheaval that will bring it crumbling to the ground. Everyone struggles with these issues while remaining blind to the true origins of their distress. The only joy these characters find is in their passion, a joy that dissipates almost as soon as it flares up. Consumed by these passions, they cannot see that they are being driven to their moral deaths. In the final ironically charged images of the play, the old guard seems to have triumphed, sitting around playing cards, while Nina is on the road to ruin, and Konstantin, despite finding some recognition as a writer, descends to suicide. But it is not the tragedy of death that we are left with; it is the absurdity of life.

The fact that The Seagull is the most-often produced of Chekhov’s plays does not mean that it is his easiest play. But one would have thought that, given some of the bold and innovative approaches so many theater artists have taken in the past while working on this play, a company as respected and revered as Antaeus would have at least steered clear of the kind of bourgeois and highly conventional production it has instead indulged in, one which finds comfort in the milieu Chekhov was being critical of. You can hear it when you enter the theater: the pre-play music is the kind of Russian folk music that evokes a lukewarm nostalgia for times gone by, which hardly anticipates the revolutionary spirit that is at the heart of the play. And one sees it in the wholly generic set design which corresponds to the flimsiness of the lives at stake here, but which otherwise gives little indication of the decay and ruin in which they are also drowning. This is a pretty visit to the Russian countryside to which we are invited, not a tragicomedy of swirling temperaments.

The fact that The Seagull is the most-often produced of Chekhov’s plays does not mean that it is his easiest play. But one would have thought that, given some of the bold and innovative approaches so many theater artists have taken in the past while working on this play, a company as respected and revered as Antaeus would have at least steered clear of the kind of bourgeois and highly conventional production it has instead indulged in, one which finds comfort in the milieu Chekhov was being critical of. You can hear it when you enter the theater: the pre-play music is the kind of Russian folk music that evokes a lukewarm nostalgia for times gone by, which hardly anticipates the revolutionary spirit that is at the heart of the play. And one sees it in the wholly generic set design which corresponds to the flimsiness of the lives at stake here, but which otherwise gives little indication of the decay and ruin in which they are also drowning. This is a pretty visit to the Russian countryside to which we are invited, not a tragicomedy of swirling temperaments.

And that brings us to the comedy. In one of the most memorable opening lines in the history of dramatic literature, Medvedenko asks Masha why she always wears black and she tells him that she is mourning for her life. There, very succinctly, the tone is set; if one finds, as one should, the balance in those lines, the comic and the tragic are joined from the very start. But Andrew J. Traister has his actors speak at a fast clip, without any emotional excess. There is nothing funny in it; there is nothing particularly sad in it. There is no sense of the self-dramatizing these people engage in. Instead, Traister seems to ask little of his actors but that they do everything with dispatch. And the comedy doesn’t breathe; instead, in order to remind us that Chekhov called the play a “comedy,” he has his actors engage in bits of comic shtick from time to time, which, particularly in the case of Arkadina, seems inappropriate and not altogether organic. If a maid responded as the maid does in this version, she would have been fired; it is done here for a cheap laugh.

What is particularly distressing is that this production comes on the heels of the recent Royal Court production that was so beautifully calibrated in every way, and which gave us, in Carey Mulligan’s willful and vulnerable Nina, the reason the play’s title refers to Nina and not really to the shot-down sea gull which stands in for what will ultimately happen to Nina. It is fascinating to see sometimes how one adjustment like that resonates and even provides all the actors with a vibe that sends them soaring. When things go that right, you never forget the sound of the horses clattering outside, the wind that howls, the crickets that sing. You remember that the paint was cracking in the Sorin household and you believed that, despite the exaggerated talk of everyone’s cheapness, there really is a problem about money.

I have seen productions that make some things so evident that one wonders why those particular concepts didn’t take hold in subsequent productions, but the fact of their existence is what finally proves how sturdy and beautiful a play it is (or can be). In the Joseph Chaikin production, Konstantin’s play – in the first scene – was taken very seriously because Chaikin was in the avant-garde himself and saw in Konstantin’s poetic ramblings the core of truth and not the piece of pretentiousness that Arkadina sees. In Andrei Serban’s interpretation, Doctor Dorn was homosexual, which explained why he keeps coming back to the household and why he loves Konstantin (and why that too is part of the cycle of unrequited love) and why he understands Masha’s misplaced passion so well (and it was so subtly acted by F. Murray Abraham). When a play that you think you know suddenly gets transformed and transcended, it is difficult to go back to the play in a production that is no better than a solid college production would be.

I have seen productions that make some things so evident that one wonders why those particular concepts didn’t take hold in subsequent productions, but the fact of their existence is what finally proves how sturdy and beautiful a play it is (or can be). In the Joseph Chaikin production, Konstantin’s play – in the first scene – was taken very seriously because Chaikin was in the avant-garde himself and saw in Konstantin’s poetic ramblings the core of truth and not the piece of pretentiousness that Arkadina sees. In Andrei Serban’s interpretation, Doctor Dorn was homosexual, which explained why he keeps coming back to the household and why he loves Konstantin (and why that too is part of the cycle of unrequited love) and why he understands Masha’s misplaced passion so well (and it was so subtly acted by F. Murray Abraham). When a play that you think you know suddenly gets transformed and transcended, it is difficult to go back to the play in a production that is no better than a solid college production would be.

There was also a famous or infamous production, depending of how you responded to it, in which a host of wonderful actors gathered together to give their acting coach, the great Mira Rostova, a chance to play Nina; Rostova proved to be too old for the part, but the rest of the cast, in such reverent support, were brilliant, and Montgomery Clift, most memorably, was as sensitive and as oddly foolish a Konstantin as one could hope for. But the production that most resembles the one Traister has put together was one I saw in Williamstown many years ago in which Nicos Psacharopoulis left the play entirely in the hands of his actors; when left on their own, actors, even the best of them – and the Williamstown cast included Lee Grant, Blythe Danner, Frank Langella, Olympia Dukakis, Kevin McCarthy – are capable of making obvious choices without strong directorial guidance. At least, in that production, the actors were fun to watch.

And so it saddens me to report that, in summing up, very little of Chekhov’s play has been looked at afresh in the Antaeus production. But this is written more in sorrow than in anger. Someone who hasn’t seen as many productions as I have will of course see the play very differently. But, seeing how many possibilities were left unexplored, this production is exasperatingly ordinary. At this point, The Seagull deserves better. It has received better.

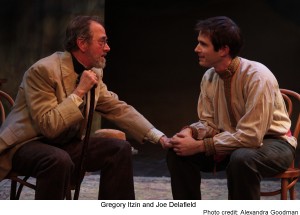

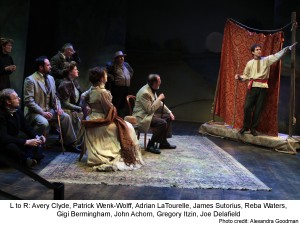

photos by Alexandra Goodman

The Seagull

a double-cast production

the “Samovars” cast is reviewed

Antaeus Theatre Company

Deaf West Theatre in North Hollywood

ends on April 15, 2012

for tickets, call 818.506.1983 or visit Antaeus