BEYOND REALISM

The living room and foyer of the modest house on 9th Street in the South Philadelphia of 1986, created by David Meyer, is as dank and dreary as social realism will allow. And when the door to the kitchen opens, we may not see the kitchen sink, but we can readily imagine exactly where it is located and what it looks like. But if you mistake Brett C. Leonard’s Ninth and Joanie for kitchen-sink drama, you will be missing the point. Under Mark Wing-Davey’s daring, audience-defying direction, this is a play in microcosm, a full-blown artistic vision of reality, as clammy and ugly as any American play has ever come to capturing the mundane grimness of working class life as brilliantly as the early plays of Harold Pinter.

You can hear it in the terseness and the uncomfortable silences of Leonard’s play, and you can see it in the way Wing-Davey attenuates each moment nearly beyond audience endurance, and you feel it in the almost agonizing stillness of the performances of this very rich ensemble, a stillness that suggests all the artifice and concentration we associate with Kabuki Theater.

You can hear it in the terseness and the uncomfortable silences of Leonard’s play, and you can see it in the way Wing-Davey attenuates each moment nearly beyond audience endurance, and you feel it in the almost agonizing stillness of the performances of this very rich ensemble, a stillness that suggests all the artifice and concentration we associate with Kabuki Theater.

There is no need to describe the plot of Ninth and Joanie because it would give away far too much of the very little that actually happens, and would, in fact, destroy the impact of what does finally erupt into explosions of emotional violence. What it is, though, is an exploration of the painful results of parental repression. This is a play about fathers and sons, about manhood and boyhood, about the impossibility at times of growing beyond childhood, when nothing is profoundly understood.

There is no need to describe the plot of Ninth and Joanie because it would give away far too much of the very little that actually happens, and would, in fact, destroy the impact of what does finally erupt into explosions of emotional violence. What it is, though, is an exploration of the painful results of parental repression. This is a play about fathers and sons, about manhood and boyhood, about the impossibility at times of growing beyond childhood, when nothing is profoundly understood.

But without giving anything away, I urge you to pay attention to the purposeful flatness each actor brings to the reading of the text; to the way Rosal Colón expresses everything she is feeling before she says one word; to the repressed anger in the frenetic dance movements of Dominic Fumusa as one son; to the laconic Beckett-like intensity that Bob Glaudini brings to the part of the father; and to the contrast provided by a refreshingly manner-free eight-year-old actor, Samuel Mercedes, as, with bright-eyed openness, he unveils the essence of innocence. And look closely at the remarkable Kevin Corrigan, as the more tortured of Glaudini’s two sons, as he moves his fingers along a Ouija Board, an extended-play piece of business that reminded me of nothing less than seeing Glenn Gould once in concert, seemingly transfixed by his own playing until artist and music merge into a single organism.

But without giving anything away, I urge you to pay attention to the purposeful flatness each actor brings to the reading of the text; to the way Rosal Colón expresses everything she is feeling before she says one word; to the repressed anger in the frenetic dance movements of Dominic Fumusa as one son; to the laconic Beckett-like intensity that Bob Glaudini brings to the part of the father; and to the contrast provided by a refreshingly manner-free eight-year-old actor, Samuel Mercedes, as, with bright-eyed openness, he unveils the essence of innocence. And look closely at the remarkable Kevin Corrigan, as the more tortured of Glaudini’s two sons, as he moves his fingers along a Ouija Board, an extended-play piece of business that reminded me of nothing less than seeing Glenn Gould once in concert, seemingly transfixed by his own playing until artist and music merge into a single organism.  And watch, too, the subtle ways Bradley King’s lighting illuminates the dark corners of the play until we recognize that, often, the dark is light enough.

And watch, too, the subtle ways Bradley King’s lighting illuminates the dark corners of the play until we recognize that, often, the dark is light enough.

This is – make no mistake about it – difficult and challenging; but if you allow the eccentricity to take hold, Ninth and Joanie is also a strangely beautiful and uncompromising vision of how far naturalism, long considered a dead-end in our post-modern time, can still go, when practiced by genuine theater artists.

photos by Kate Edwards

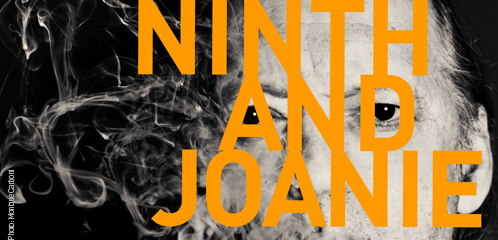

Ninth and Joanie

Labyrinth Theater Company at Bank Street Theater

scheduled to end on May 6

for tickets, visit http://labtheater.org/Ninth-And-Joanie/