WHAT WE HAVE HERE IS A FAILURE TO COMMUNICATE

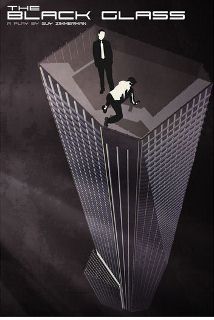

Somewhere around half-way through Guy Zimmerman’s The Black Glass, a “Hollywood Fringe Festival premiere,” my mind began to wander. Every opportunity for me to jump on board with this dense, impenetrable, and esoteric mess had been squandered by abstruse writing, obscured plot, elusive character development, and unimaginative direction (also by Zimmerman). Every budding playwright should see this show, I thought, because it is a perfect template of a playwright’s blunders and self-indulgences.

We are in the high-rise office of Donald Bentham (John Lacy), who is some kind of Wall Street tycoon with a dark past. Also in the office is the ghost of Thomas McGivern (Brad Culver), Bentham’s half-brother, who was somehow killed by the unscrupulous magnate. In tow with the dead brother are two women, a Greek Chorus who are some kind of demonic lesbian cougars (Elizabeth Greer and Martha Demson). Off in Spain is Bentham’s daughter Joanna (Diana Wyenn), a porn star dressed like a matador, but her doppelganger also haunts the scene. What exactly happened to whom is pure speculation on the part of the audience.

What is clear is that Zimmerman has an agenda about capitalism. In the program notes, he dedicates the play to the hundreds of thousands of citizens in the Occupy movements who protested “thirty years of neoliberal economic assault from above.” Even that statement is vague. Um, above what? Does Zimmerman mean from the top floors of some towering building? I gather that Zimmerman blames a handful of industrialists for our economic woes, because he kills off Bentham in the end (at least, I think he does – the cougar chorus slashes him with some mini-Samurai swords a la Kill Bill, but he may have committed suicide by jumping from the tower, or the whole enterprise is some sort of dream). The point is that Zimmerman knows what he wants to say, but he doesn’t have a story – and what little plot there is gets delivered in deconstructed ways where nothing is linear. There’s no conflict, no arc, and no character. Nothing else matters here except Zimmerman and his desire to effect change.

What is clear is that Zimmerman has an agenda about capitalism. In the program notes, he dedicates the play to the hundreds of thousands of citizens in the Occupy movements who protested “thirty years of neoliberal economic assault from above.” Even that statement is vague. Um, above what? Does Zimmerman mean from the top floors of some towering building? I gather that Zimmerman blames a handful of industrialists for our economic woes, because he kills off Bentham in the end (at least, I think he does – the cougar chorus slashes him with some mini-Samurai swords a la Kill Bill, but he may have committed suicide by jumping from the tower, or the whole enterprise is some sort of dream). The point is that Zimmerman knows what he wants to say, but he doesn’t have a story – and what little plot there is gets delivered in deconstructed ways where nothing is linear. There’s no conflict, no arc, and no character. Nothing else matters here except Zimmerman and his desire to effect change.

My wandering mind then drifted back to 1990, the year that a seminal theatergoing experience occurred when I saw John Guare’s Six Degrees of Separation. Not only did Guare have a fascinating story to tell (a con man infiltrates the life of an Upper East Side art-loving socialite), but he deconstructed what could easily have been linear storytelling. The way that he splintered and cut-and-paste his story was triumphant because he was examining the fractured nature of his characters. In that context, even actors who broke the fourth wall to deliver monologues was a transcendent experience. Above all, as the title suggests, Guare (as with Arthur Miller) delved into the universality surrounding his characters; he wanted us to observe the interconnections between all peoples and times, and the effect fame and power of any one person can have on all of us. (I firmly assert that this play was also the genesis of the now ubiquitous “90-Minute-No-Intermission” phenomenon.)

My wandering mind then drifted back to 1990, the year that a seminal theatergoing experience occurred when I saw John Guare’s Six Degrees of Separation. Not only did Guare have a fascinating story to tell (a con man infiltrates the life of an Upper East Side art-loving socialite), but he deconstructed what could easily have been linear storytelling. The way that he splintered and cut-and-paste his story was triumphant because he was examining the fractured nature of his characters. In that context, even actors who broke the fourth wall to deliver monologues was a transcendent experience. Above all, as the title suggests, Guare (as with Arthur Miller) delved into the universality surrounding his characters; he wanted us to observe the interconnections between all peoples and times, and the effect fame and power of any one person can have on all of us. (I firmly assert that this play was also the genesis of the now ubiquitous “90-Minute-No-Intermission” phenomenon.)

Sadly, since then, American theatre has become a logjam of plays in which a wafer-thin story is given a stylistic approach that does nothing to support the story. It is style over substance, concept over storytelling, and clever dialogue in lieu of motivated, three-dimensional characters. What the hell is going on with the art of storytelling in the theater? Perhaps both the sound-bites of 24-hour news and the truncated communiques of social media are numbing our modern playwrights, most of whom believe that self-indulgent, poetical wordplay is a rational substitute for plot. And forget about creating fascinating characters.

Sadly, since then, American theatre has become a logjam of plays in which a wafer-thin story is given a stylistic approach that does nothing to support the story. It is style over substance, concept over storytelling, and clever dialogue in lieu of motivated, three-dimensional characters. What the hell is going on with the art of storytelling in the theater? Perhaps both the sound-bites of 24-hour news and the truncated communiques of social media are numbing our modern playwrights, most of whom believe that self-indulgent, poetical wordplay is a rational substitute for plot. And forget about creating fascinating characters.

The talented actors are completely wasted. Brad Culver (who also played a dead guy in How to Disappear Completely) could mesmerize me by reading the program notes, but he has nothing to work with here. As the man caught in a web of industrialism, John Lacy comes off like a car dealer having a bad day, slamming back drinks without becoming drunk, and loudly slamming down his glass to show emotion. Greer and Demson are definitely having fun, as if they were trying to stir things up at a deadly cocktail party, and poor Ms. Wyenn has been directed with no sense of time, history or place. (How can a writer expect to grow if they keep directing their own material? Was it arrogance on the part of Mr. Zimmerman that nobody could interpret his baby but him?)

The talented actors are completely wasted. Brad Culver (who also played a dead guy in How to Disappear Completely) could mesmerize me by reading the program notes, but he has nothing to work with here. As the man caught in a web of industrialism, John Lacy comes off like a car dealer having a bad day, slamming back drinks without becoming drunk, and loudly slamming down his glass to show emotion. Greer and Demson are definitely having fun, as if they were trying to stir things up at a deadly cocktail party, and poor Ms. Wyenn has been directed with no sense of time, history or place. (How can a writer expect to grow if they keep directing their own material? Was it arrogance on the part of Mr. Zimmerman that nobody could interpret his baby but him?)

So here’s my question to Mr. Zimmerman, since Wall Street is on his mind: What happens if America finally topples the 1%? Are you not then still left with 99% of an insatiable consumer-base who were responsible for creating that 1% in the first place? We need conflict in the theatre, not one-sided agendas in which the playwright is the only one who knows what he’s trying to say. There are two sides to every story. But in the end it doesn’t matter because it’s impossible to empathize with your ambition to annihilate injustice when you offer no story in the first place.

photos by Maia Rosenfeld

The Black Glass

Presented by Open Fist and Padua Playwrights at Open Fist Theatre in Hollywood (Los Angeles Theater)

scheduled to end on Jun 24

for tickets, visit http://www.hff12.org/892.com/