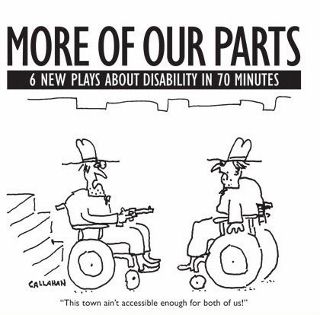

MORE IS LESS THAN THE SUM OF ITS PARTS

When making a show consisting of several short plays about the disabled, one must be concerned, it seems, with the possibility of the whole thing becoming more about message than art. It’s unlikely under such circumstance that, for example, a disabled character, say a wheelchair-bound girl, feed poisoned bread to ducks in the park. Or that a young man with Down syndrome punches his pretty, young caretaker in her face. Or that a deaf teenager is caught masturbating because he doesn’t hear the door open behind him. Unfortunately, none of this happens in More of Our Parts. Producing company Theater Breaking Through Barriers may be dedicated to advancing actors and writers with disabilities and changing the image of people with disabilities from dependence to independence, but the whole idea of writing a bunch of short plays involving people with disabilities, based on results at the Clurman Theater, seems a bit contrived. Up to now, how many playwrights have actually found themselves inspired to write a ten minute play about such individuals? Judging by the decidedly mixed results in More of Our Parts, not many.

The first mini-play is Bruce Graham’s The Ahhh Factor, directed by Russell Treyz. Screenwriter Jerry (Jonathan Todd Ross) inserts a topless post-coital scene into a big-budget vehicle for a deaf movie star (think Marlee Matlin) and Robert, the film’s limp director (the perfectly uncomfortable Warren Kelley), tries to convince him to take it out, squeamish as he is about showing the breasts of a hearing-impaired woman. This little skit felt like it took about an hour to write. It’s devoid of any real drama: Both the deaf movie star and the film’s producers want to leave the topless scene in and Robert, the director, has neither sway nor investment in this issue. If Mr. Graham was attempting to explore the theme of society’s discomfort with viewing the disabled as sexual beings, then he should have made the scene not between a writer and a director, who in this case are both hired hands, but between the deaf movie star actress, who wants to be topless, and the film’s producer, who is against it.

The first mini-play is Bruce Graham’s The Ahhh Factor, directed by Russell Treyz. Screenwriter Jerry (Jonathan Todd Ross) inserts a topless post-coital scene into a big-budget vehicle for a deaf movie star (think Marlee Matlin) and Robert, the film’s limp director (the perfectly uncomfortable Warren Kelley), tries to convince him to take it out, squeamish as he is about showing the breasts of a hearing-impaired woman. This little skit felt like it took about an hour to write. It’s devoid of any real drama: Both the deaf movie star and the film’s producers want to leave the topless scene in and Robert, the director, has neither sway nor investment in this issue. If Mr. Graham was attempting to explore the theme of society’s discomfort with viewing the disabled as sexual beings, then he should have made the scene not between a writer and a director, who in this case are both hired hands, but between the deaf movie star actress, who wants to be topless, and the film’s producer, who is against it.

In Jeffrey Sweet’s A Little Family Time, directed by Patricia Birch (Grease), distinguished writer and humanitarian Eli (a wonderfully candid and balanced Shawn Elliott), discusses some final edits to a human rights speech with his fiancé Annette (the first-rate Donna Bullock), when he’s interrupted by Nell (Blair Wing), who proceeds to usher in Eli’s estranged son Lewis (Joshua Eber), a young man afflicted with Down syndrome whose existence was hitherto unknown to Annette.

In Jeffrey Sweet’s A Little Family Time, directed by Patricia Birch (Grease), distinguished writer and humanitarian Eli (a wonderfully candid and balanced Shawn Elliott), discusses some final edits to a human rights speech with his fiancé Annette (the first-rate Donna Bullock), when he’s interrupted by Nell (Blair Wing), who proceeds to usher in Eli’s estranged son Lewis (Joshua Eber), a young man afflicted with Down syndrome whose existence was hitherto unknown to Annette.

A Little Family Time is generally a solid little play, but, as unseemly as this may be to admit, the problem is with the casting of Mr. Eber, who does in fact have Down syndrome. As soon as he appears on stage we are no longer watching the play, we are watching him, not as his character but as an actor with Down syndrome. Mr. Eber glanced into the audience at one point and, to an untrained ear, his vocal inflections made some of his dialogue unintelligible. Casting mentally challenged individuals can work in film, where every detail in every frame can be controlled, but it can be distracting in the theater. Simply stated, as soon as Mr. Eber comes out on stage the show feels manufactured. Again, it’s that fine line between a well-intentioned theater company and the finished product put before the public.

Bekah Brunstetter’s After Breakfast, Maybe, directed by Christina Roussos, is a simple little gem of a play about Diane (Melanie Boland), a loving and well-meaning mother who is having breakfast with her feisty, wheelchair-bound daughter Marcy (the dynamic Shannon DeVido). Frightened, defeatist and passive-aggressive, Diane wants what she thinks is best for Marcy, which in her mind is a quiet little unassuming life, whereas Marcy wants to “take over the world.” Marcy is fearless and capable but confined to a wheelchair. It is an unsolvable problem that is dealt with gently and without melodrama. The characters and conflicts ring true and the conclusion is an appropriately tiny victory (if only Donald Short’s thunder sound effect was not overused).

Bekah Brunstetter’s After Breakfast, Maybe, directed by Christina Roussos, is a simple little gem of a play about Diane (Melanie Boland), a loving and well-meaning mother who is having breakfast with her feisty, wheelchair-bound daughter Marcy (the dynamic Shannon DeVido). Frightened, defeatist and passive-aggressive, Diane wants what she thinks is best for Marcy, which in her mind is a quiet little unassuming life, whereas Marcy wants to “take over the world.” Marcy is fearless and capable but confined to a wheelchair. It is an unsolvable problem that is dealt with gently and without melodrama. The characters and conflicts ring true and the conclusion is an appropriately tiny victory (if only Donald Short’s thunder sound effect was not overused).

Neil LaBute’s The Wager and A.R. Gurney’s The Interview were directed by Artistic Director Ike Schambelan, who appeared to be truly incapacitated as both playwrights didn’t give him much to work with. Both plays take place on the same abstract and rather dull set as the other pieces (designed by Nicholas Lazzaro).

The Wager explores an encounter between a yuppie named Guy, (Nicholas Viselli), his trophy girlfriend Gal (a delightfully vacuous Tiffan Borelli), and a Homeless Dude in a wheelchair (a very naturalistic Shawn Randall). Guy proposes a wager to Homeless Dude – guess which hand the dollar is in and you get the dollar, guess wrong and I get to punch you. There are several twists to this unbelievable drivel, none of which carry any dramatic weight. An eye-rolling waste of 10 minutes. (Ironically, this was the play I really wanted to see.)

The Wager explores an encounter between a yuppie named Guy, (Nicholas Viselli), his trophy girlfriend Gal (a delightfully vacuous Tiffan Borelli), and a Homeless Dude in a wheelchair (a very naturalistic Shawn Randall). Guy proposes a wager to Homeless Dude – guess which hand the dollar is in and you get the dollar, guess wrong and I get to punch you. There are several twists to this unbelievable drivel, none of which carry any dramatic weight. An eye-rolling waste of 10 minutes. (Ironically, this was the play I really wanted to see.)

The Interview, with another unimpressive performance by Mr. Viselli, has him playing Howard, father to deaf son Ken (Stephen Drabicki), who discloses that he refused to wear his hearing aids during a college admissions interview. Ostensibly, this play is about a young man who doesn’t want to appear disabled and/or for the world to treat him as such. Unfortunately, there’s no real drama, no sense of stakes. We might be able to guess why not wearing his hearing aids is important, but we never feel it; Mr. Gurney does not supply the details necessary to enter Ken’s world.

The Interview, with another unimpressive performance by Mr. Viselli, has him playing Howard, father to deaf son Ken (Stephen Drabicki), who discloses that he refused to wear his hearing aids during a college admissions interview. Ostensibly, this play is about a young man who doesn’t want to appear disabled and/or for the world to treat him as such. Unfortunately, there’s no real drama, no sense of stakes. We might be able to guess why not wearing his hearing aids is important, but we never feel it; Mr. Gurney does not supply the details necessary to enter Ken’s world.

Finally Geese, written by Samuel D. Hunter and directed by Christopher Burris, starts off with the questionable premise in which a Parks Department employee named Ben (the strikingly handsome David Marcus) is sent out to capture geese grazing in the park. There is an overpopulation and they have become a hazard to air travel, so the captured birds will be subsequently exterminated. Melanie (another convincing performance by DeVido), a young woman in a wheelchair, sets out to stop Ben from completing his mission. In aid of this, she tries to enlist the public (Boland, Borelli, Randall and Ross) using her disability as a tool of manipulation. Geese brings up some potentially compelling themes, which it never really delves into. But the play’s goal seems to be simply to capture a brief interaction between Melanie and Ben, which it does nicely, furnishing some sweet, charming moments.

Finally Geese, written by Samuel D. Hunter and directed by Christopher Burris, starts off with the questionable premise in which a Parks Department employee named Ben (the strikingly handsome David Marcus) is sent out to capture geese grazing in the park. There is an overpopulation and they have become a hazard to air travel, so the captured birds will be subsequently exterminated. Melanie (another convincing performance by DeVido), a young woman in a wheelchair, sets out to stop Ben from completing his mission. In aid of this, she tries to enlist the public (Boland, Borelli, Randall and Ross) using her disability as a tool of manipulation. Geese brings up some potentially compelling themes, which it never really delves into. But the play’s goal seems to be simply to capture a brief interaction between Melanie and Ben, which it does nicely, furnishing some sweet, charming moments.

Creating an evening of short plays around a common theme is nothing new, but it’s a tricky enterprise. With gay marriage as its theme, Standing on Ceremony flourished because each gay wedding play therein was a terrific piece of writing (including one from LaBute), and the show was a resounding success, even as actors delivered lines without memorization from music stands. The plays in More of Our Parts are by and large not exceptional enough for the evening to achieve a higher purpose.

photos by Carol Rosegg

More of Our Parts

Theater Breaking Through Barriers at The Clurman Theater in New York City

scheduled to end on July 1, 2012

for tickets, visit http://www.tbtb.org/

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Insightful and constructive.