NO EVIL. NO GOOD.

There are few who do not know the story. The devil possesses Regan, the innocent 12-year-old daughter of movie star Chris MacNeil, who is working on a film in Georgetown. A bevy of fascinating characters, most of whom are experiencing a crisis of faith (religious or otherwise), become tested to their limit, and the story culminates in an exorcism performed by local priest Damian Karras and elderly clerical archaeologist Father Merrin. In adapting William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist for the stage, playwright John Pielmeier (Agnes of God) wisely decided to eschew the vivid bodily fluids, special effects, and faraway locales that we associate with the iconic movie, concentrating instead on the fascinating subject of good and evil. The problem is that Pielmeier doesn’t trust the story, going so far as to drop the subplot involving a police detective investigating a murder. Too much time is spent on religious discourse; main characters are saddled with mannered dialogue that often has them brooding about the nature of good and evil. Why not just tell us the story and let us take away from it what we will?

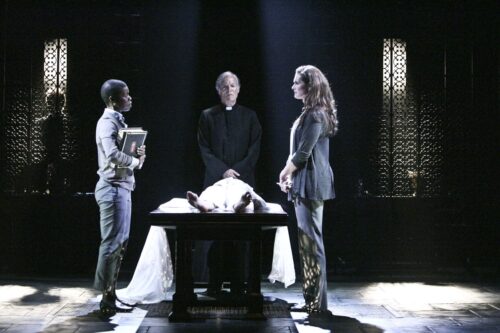

More glaringly, the world premiere production cannot levitate from the construction of the play itself, which allows for scenes to be punctuated by Father Merrin, who breaks the fourth wall with annotative ruminations on good vs. evil. And because Richard Chamberlain plays the titular character with resonant mellifluousness, he comes off more like a tongue-in-cheek history professor than a world-weary, nitroglycerin-popping demon-chaser.

A stage adaptation of the novel (not of the subsequent film, which is emblazoned in most spectators’ minds) seems doomed from the start. While the devil remains in the details, there are certainly glimpses that validate Pielmeier’s vision of a trimmed-down Exorcist, although it’s doubtful that it will one day become a successful stage adaptation. Pielmeier successfully splices some of the novel’s characters, and embellishes others in the first scene. Assistant Sharon and servants Karl and Willie have been amalgamated into Carla, a Rwandan émigré with a dark past involving atrocities. The effete, alcoholic film director Burke Dennings is now much chummier with Regan, and, as mentioned in the book, is an ex-seminarian, but now there is more back story and added information: he attends mass ’” drunk ’” and has a giant, rood-like smudge of ash on his forehead, being that it’s Ash Wednesday. Burke, especially as played by the magnificent Harry Groener, is a fully well-rounded character, even though he appears as comic relief.

Events from the novel have been rightfully condensed into this primary scene as well: rats in the attic, the Ouija Board, “Captain Howdy,” etc. There is even a sense of history between the characters, and Pielmeier has an ear for dialogue that capably negotiates character development, thematic issues, exposition, and humor.

What makes the film and novel so unsettling is that such an act of evil can happen in a comfortable Georgetown home, or that violent desecration can occur in a neighborhood church. Pielmeier’s concept of a bare-bones production involves an empty stage with table and chairs, thus allowing the actors to create each scene. But the idea, one which presumptively universalizes evil, backfires. Director John Doyle, who triumphed with his unembellished productions of Sweeney Todd and Company, opted for cinematic trickery to unnerve us, utilizing sound – Dan Moses Schreier’s very loud raps, squeaks, and echoes – and a musical score by no less than Sir John Tavener.

Scott Pask’s scenic design is disconcerting at best: a giant cross, from which pale-red water emanates at the climax, metaphorically looms over the ninety-five minute proceedings alongside a sanctuary lamp; religious artifacts are used as props (Communion Cup=Burke’s tumbler, ciborium=Ouija Board, Corporal=bed sheet, etc.); the perimeter is a wrought-iron church gate; and the back wall contains rows of windows, suggesting a monastery. The obviousness of the design actually adds nothing to the religious aspect of the play or the story, and most certainly detracts us from seeing the various settings (graveyard, doctor’s office) in our mind’s eye. Pask’s costumes are unremarkable, but Jane Cox’s lighting design is exquisite.

Opinions about Brooke Shields’ performance as the famous actress Chris MacNeil (a character based on Shirley MacLaine) will vary wildly. Ms. Shields is admirable, but wholly miscast. To start with, she is simply not a captivating actress. She certainly hits all the right notes, as they say, but her actual tears and forceful shouting feel superficial; she lacks the emotional magnitude and keen insight required for such a role.

Honestly, other than Groener, the only two actors who could rise above the material are Roslyn Ruff as Carla, and Emily Yetter as Regan. Ms. Ruff brought a sincerity, vulnerability and staid demeanor to create a multi-dimensional character. The gymnastically pliable Yetter nailed the girl’s innocence, and offered demonic glares that would make Damian from The Omen blush. The rest of the cast — Manoel Feliciano, David Wilson Barnes, Tom Nelis, and Stephen Bogardus — simply gets lost, as they are in service to a play which lacks verisimilitude (and if the play isn’t going for reality, the employment of Penn [from “Penn and Teller”] to create the one trick in the show — a levitation, defies explanation — perhaps they were trying to rise above the material).

The play’s final moment sums up the problematic venture at the Geffen Playhouse: With no dramatic intrigue whatsoever, Merrin sits in a chair, rubs his arm, slumps over ever so slightly, and dies. Then the denouement: Karras double-dares the devil to take him instead of the girl, at which time the beast possesses the priest. Karras then heroically impales himself in the chest with a gilded cross (which miraculously acts as a switchblade), and Regan calls for her mother. As Tavener’s eclectic and distracting music begins to fade, the actors (still in character) face out to the audience as if they were a photo for “Exorcist: The Ride,” and up pops the dead Merrin (still in character, mind you), who walks center stage to wrap up the story, and tell us to believe in the possibility of hope. It’s anti-climactic and unnecessary; Charles Boyer didn’t need to look directly into the camera in Gaslight to illuminate the workings of evil.

photos by Michael Lamont

The Exorcist

Geffen Playhouse in Westwood

ends on August 12, 2012

for tickets, call 310.208.5454 or visit Geffen Playhouse

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

See? This is what happens when you don’t issue instruments to your actors.

I say, rework this with accordions and bagpipes.

The Geffen presents more junk than imaginable.

My father (the author of The Exorcist) was not impressed with how this play turned out although he thought some of the acting good. Hope the upcoming production in London is better.

Michael Blatty

Portland, Oregon