THE GOOD THAT COULD HAVE BEEN BETTER

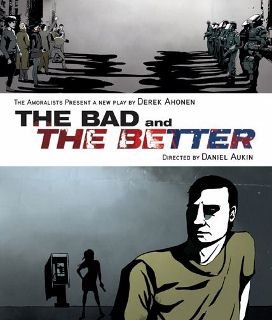

Watching The Amoralists’ production of Derek Ahonen’s entertaining new play The Bad and The Better, an image comes to mind of a virtuoso juggling act, with Mr. Ahonen and director Daniel Aukin keeping 26 actors, over 30 characters, and an extraordinary number of plot lines in the air at once with nearly flawless technique.

Mr. Ahonen’s play has enough plot for a 400-page novel: An idiot politician, Eugene Moretti (an appropriately clownish David Lanson) is running for New York State governor. Zorn, a wealthy and ruthless developer (a frighteningly real Clyde Baldo) is trying to get him elected on an anti-terrorist platform. A group of young anarchists (Byron Anthony, Selene Beretta, Regina Blandón, James Kautz, Nick Lawson, Chris Wharton) are working to disrupt the status quo, with a focus on Zorn but with conflicting ideas regarding how to go about this. Venus (David Nash), an undercover cop, infiltrates the anarchists and begins an affair with Faye, one of its members (Anna Stromberg), creating a love triangle between him, her, and his cop-bar bartender girlfriend Matilda (precisely characterized by Cassandra Parras).

Then there’s Venus’s brother, Ricky Lang (a sympathetically hapless William Apps), an alcoholic police detective assigned to working in the sticks after a questionable shooting. Lang is trying to solve a couple of murder-suicides, which may or may not have something to do with a massive real estate venture, all while dealing with his insanely jealous wife Connie (Judy Merrick) and lovesick secretary, Miss Hollis, who may well be deranged (Sarah Lemp in a fittingly neurotic performance). These are only some of the plot lines and characters; there are others, each with their own subplots and storylines. Remarkably, all the threads come together in the end, leaving, in the ominous parlance of the genre, no loose ends.

Then there’s Venus’s brother, Ricky Lang (a sympathetically hapless William Apps), an alcoholic police detective assigned to working in the sticks after a questionable shooting. Lang is trying to solve a couple of murder-suicides, which may or may not have something to do with a massive real estate venture, all while dealing with his insanely jealous wife Connie (Judy Merrick) and lovesick secretary, Miss Hollis, who may well be deranged (Sarah Lemp in a fittingly neurotic performance). These are only some of the plot lines and characters; there are others, each with their own subplots and storylines. Remarkably, all the threads come together in the end, leaving, in the ominous parlance of the genre, no loose ends.

There is much to pay attention to and enjoy in this absurdist, ironic, noirish, melodramatic bit of stylized pulpy fluff: a byzantine plot; crisply defined characters; engaging performances; serviceable costumes (Moria Clinton); and precise blocking of sometimes very complex scenes, with often a few different scenes happening nearly simultaneously in the same space. These are masterfully delineated by Mr. Aukin with the aid of Natalie Robin’s terrific lighting, Phil Carluzzo’s sound, and Alfred Schatz’ set, one that is robust and literal yet versatile.

There is much to pay attention to and enjoy in this absurdist, ironic, noirish, melodramatic bit of stylized pulpy fluff: a byzantine plot; crisply defined characters; engaging performances; serviceable costumes (Moria Clinton); and precise blocking of sometimes very complex scenes, with often a few different scenes happening nearly simultaneously in the same space. These are masterfully delineated by Mr. Aukin with the aid of Natalie Robin’s terrific lighting, Phil Carluzzo’s sound, and Alfred Schatz’ set, one that is robust and literal yet versatile.

Despite all the wonderful inventiveness and inspiration that clearly went into The Bad and The Better, the show does have three major shortcomings (as well as a few minor ones), which are not hard to spot. For one thing, Mr. Nash, who clearly put a great deal of effort into his performance, regrettably made a bad acting choice in trying to play his character as a straight up tough guy. Mr. Nash is physically small, short and skinny, and his goal, seemingly, was to give his character mass and size by expanding his chest and shoulders, deepening his voice, talking loud and wearing a scruffy beard. Unfortunately, he is unconvincing (especially when his character carries Faye, a thin young woman, in his arms; Mr. Nash can barely manage it). Mr. Nash tries to play his character like a gorilla but it might have been more effective to play him like a mongoose; a razor blade instead of a sledgehammer.

Despite all the wonderful inventiveness and inspiration that clearly went into The Bad and The Better, the show does have three major shortcomings (as well as a few minor ones), which are not hard to spot. For one thing, Mr. Nash, who clearly put a great deal of effort into his performance, regrettably made a bad acting choice in trying to play his character as a straight up tough guy. Mr. Nash is physically small, short and skinny, and his goal, seemingly, was to give his character mass and size by expanding his chest and shoulders, deepening his voice, talking loud and wearing a scruffy beard. Unfortunately, he is unconvincing (especially when his character carries Faye, a thin young woman, in his arms; Mr. Nash can barely manage it). Mr. Nash tries to play his character like a gorilla but it might have been more effective to play him like a mongoose; a razor blade instead of a sledgehammer.

Another issue is a few ludicrous plot points, which shake, if not tear, our suspension of disbelief. If nothing else, these unbelievable twists distract from the action as, instead of watching the progression of the show, one finds oneself (at least I did) ruminating on the possibility (or, more to the point, the impossibility) of what one has just witnessed.

Another issue is a few ludicrous plot points, which shake, if not tear, our suspension of disbelief. If nothing else, these unbelievable twists distract from the action as, instead of watching the progression of the show, one finds oneself (at least I did) ruminating on the possibility (or, more to the point, the impossibility) of what one has just witnessed.

I can hear the counterargument to this now: “The play is supposed to be over-the-top and absurd, that’s part of the point!â€

Which leads to the third problem: For all its plot, characters and themes, The Bad and The Better doesn’t really have much to say; there is no lingering aftertaste when you get home, you’ve eaten a lovely desert but that’s it. In this light the “absurd†argument doesn’t work. Absurdity in an artistic work is meaningful when it reveals some higher truths about life, society, the human condition, etc. When it doesn’t, it’s just sloppy writing and/or a bit of a cheat: artistic absurdity is like poetry and when it’s off, it’s painfully off.

Ordinarily, this would be a serious problem. But in the case of The Bad and The Better it’s tempting to let the issue slide. The sense one gets is that the creative team behind the show wanted to do something baroque and labyrinthine, to play characters and situations (almost?) impossible to legitimately squeeze into a single show, and if a little cheating was necessary to achieve this, then so be it. In this sense the show is like an exercise (albeit an extraordinarily complex and beautifully polished one), but a worthwhile and delightful exercise nonetheless.

Ordinarily, this would be a serious problem. But in the case of The Bad and The Better it’s tempting to let the issue slide. The sense one gets is that the creative team behind the show wanted to do something baroque and labyrinthine, to play characters and situations (almost?) impossible to legitimately squeeze into a single show, and if a little cheating was necessary to achieve this, then so be it. In this sense the show is like an exercise (albeit an extraordinarily complex and beautifully polished one), but a worthwhile and delightful exercise nonetheless.

photos by Monica Simoes

The Bad and The Better

The Amoralists and The Peter Jay Sharp Theater in New York City (New York Theater)

scheduled to end on July 21, 2012

for tickets, visit http://www.thebadandthebetter.com/