POETRY OUT OF MOTION

I was quite keen to see Amy Freed’s The Psychic Life of Savages; curious about its fictional take on Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, the dead, messy poet heroines of my angst-ridden teenaged years. I would read Plath’s ripe paean to father fixation and suicide, Lady Lazarus, over and over’”bathing in what I believed was our shared sense of exquisite agony. And once I read how Anne Sexton had written the first drafts of The Awful Rowing Toward God in twenty days with “two days out for despair and three days out in a mental hospital,” I viewed her as a similar kindred soul.

That was then and this is now. The coolness of suicide to a teen morphs in adulthood to a broader view that encompasses other concerns: Suddenly the hitherto peripheral fact that Plath killed herself with her kids in the next room’”that they could have suffocated on the same gas no matter how well she thought she had sealed off the room’”becomes a defining fact.

That was then and this is now. The coolness of suicide to a teen morphs in adulthood to a broader view that encompasses other concerns: Suddenly the hitherto peripheral fact that Plath killed herself with her kids in the next room’”that they could have suffocated on the same gas no matter how well she thought she had sealed off the room’”becomes a defining fact.

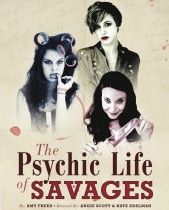

Still, the fascination with their suffering persists. The Psychic Life of Savages plays peek-a-boo with the idea of Plath and Sexton as make believe characters’”giving them and their fictional counterparts Ted Hughes and Robert Lowell different last names. A ghostly Emily Dickinson does keep her own full name, which is ironic, since her banshee, whack-a-doo stage character bears the least resemblance to the real deal, while the other four are closer to the mark in varying degrees.

The first act starts well, with well-observed vignettes of the characters meeting, and Freed has written poetry for most of the characters that they are meant to have written themselves, that to my ear sounds plausible enough. Directors Angie Scott and Nate Edelman keep the pace going, and the laughs are plentiful, until we’re back for the second act and we suddenly realize that characterization, behavior, and pace is all we’re going to get. There’s no momentum toward anything other than dabbling in neuroses. And it starts feeling teenaged in the worst sense’”sophomoric indulgence masked as sophistication.

The first act starts well, with well-observed vignettes of the characters meeting, and Freed has written poetry for most of the characters that they are meant to have written themselves, that to my ear sounds plausible enough. Directors Angie Scott and Nate Edelman keep the pace going, and the laughs are plentiful, until we’re back for the second act and we suddenly realize that characterization, behavior, and pace is all we’re going to get. There’s no momentum toward anything other than dabbling in neuroses. And it starts feeling teenaged in the worst sense’”sophomoric indulgence masked as sophistication.

Everyone is so intent on showing us just how artistically, theatrically, kookily crazy they are, they sidestep the process of making these characters into human beings. The dialogue crackles, not just with wit and intelligence, but also with feeling. It’s the production that falters, coming across as more of a school play than anything else. (I made this observation to my companion at the performance before reading in the program that the players are comprised of a group of recent UCLA theater graduates who call themselves the Savage Players.)

The standout performance is Josephine Keefe as Sylvia. She gets it right’”the physicality, fragility, mania, and spontaneity. She modulates her performance pitch, drawing us in before pushing us away again; teasing and taunting as her character’s commitment to self-expression ebbs and flows. As her professor and then husband Ted (based on the future British Poet Laureate Ted Hughes), Colin Simon looks all angular and rumpled in the right ways, but he is hampered by a wildly fluctuating British accent that can’t make up its mind where it’s from: Mayfair? Manchester? Wales? Ireland? A little bit of everything gets thrown in, and Simon’s intensity level is always at full volume. He never stops yelling at us. Of course, Sylvia grows exasperated. We all do.

The standout performance is Josephine Keefe as Sylvia. She gets it right’”the physicality, fragility, mania, and spontaneity. She modulates her performance pitch, drawing us in before pushing us away again; teasing and taunting as her character’s commitment to self-expression ebbs and flows. As her professor and then husband Ted (based on the future British Poet Laureate Ted Hughes), Colin Simon looks all angular and rumpled in the right ways, but he is hampered by a wildly fluctuating British accent that can’t make up its mind where it’s from: Mayfair? Manchester? Wales? Ireland? A little bit of everything gets thrown in, and Simon’s intensity level is always at full volume. He never stops yelling at us. Of course, Sylvia grows exasperated. We all do.

Bryan Chesters has the pedantic self-involvement one imagines Robert Lowell might (or might not) have had, but he isn’t able to translate that into a character motivated by anything more than hearing himself speak. That’s a good place to start, but not a satisfying place to finish. Certainly there must be more to mine in the life of even a pretend Lowell’”a man who was regarded in his day as one of the finest poets ever produced in this country, and was American Poet Laureate. Lauren Dunagan looks terrific as Anne Sexton, dressed mainly in bedclothes, hair askew, boozy, and beautiful. Yet Dunagan never manages to make Anne’s turmoil feel genuine, so there’s nothing at stake.

Bryan Chesters has the pedantic self-involvement one imagines Robert Lowell might (or might not) have had, but he isn’t able to translate that into a character motivated by anything more than hearing himself speak. That’s a good place to start, but not a satisfying place to finish. Certainly there must be more to mine in the life of even a pretend Lowell’”a man who was regarded in his day as one of the finest poets ever produced in this country, and was American Poet Laureate. Lauren Dunagan looks terrific as Anne Sexton, dressed mainly in bedclothes, hair askew, boozy, and beautiful. Yet Dunagan never manages to make Anne’s turmoil feel genuine, so there’s nothing at stake.

I don’t care for the playwrights conception of Emily Dickinson: Ms. Freed makes the fabled Belle of Amherst into a hysterical wraith from a Victorian penny dreadful. Actress Anne Elizabeth Butler flounders with the material, shrieking and waving her arms about with little connection to organic emotion.

I don’t care for the playwrights conception of Emily Dickinson: Ms. Freed makes the fabled Belle of Amherst into a hysterical wraith from a Victorian penny dreadful. Actress Anne Elizabeth Butler flounders with the material, shrieking and waving her arms about with little connection to organic emotion.

Presented by the Latino Theater Company (for no discernible reason, since there are no Latinos on stage and no exploration of anything to do with Latino culture in the play) and the Savage Players, this feels like a vanity production more than anything else. And two words about electric cigarettes: Stop it. They’re distractingly artificial in a period setting, all vapor, with the actors lighting up like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. Either flout the law and smoke for real or give it up cold turkey.

photos by April Shih, Pablo Santiago and Lauren Dunagan

The Psychic Life of Savages

presented by The Latino Theater Company & Savage Players at LATC

through August 16, 2012

for tickets, visit http://www.thelatc.org

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

I hope that readers of this review will see that Mr. Bernstein has forgotten the first principle of reviewing, as stated by Henry James: “We must grant the artist his subject, his idea; our criticism is applied only to what he makes of it.” Evidently, Mr. Bernstein came expecting to see realistic representations of poets he admires, rather than the darkly comic distortions of them that the play presents–and in the case of Emily Dickinson, a hallucinatory alter-ego projection by a suicidal woman undergoing shock therapy. Mr. Bernstein finds the other characters besides Dickinson “closer to the mark in varying degrees.” Whose mark? And having made a fundamental critical error, he fluctuates between blaming the play and blaming the actors for not living up to his mistaken expectations. I was privileged to see this production on its preview night and thought it consistently engaging and all the actors fresh and interesting. Anyone who enjoys exciting, stimulating theater should see it.