THREE DEGREES OF SEPARATION

A woman asks for a martini in a highball glass and accuses her husband of peeing in the sink’¦ again. He doesn’t cop to it, but doesn’t deny it. The couple seems long married, used to one another, and not particularly happy’”probably in their 60s or early 70s. She’s nursing a hangover’”an event that appears to be numbingly normal in this couple’s life.

Then a disheveled woman comes in, apparently unseen by the couple; she destroys a painting and hurls it outside. A neighbor checks on the first couple and she brings an unwanted casserole. The disheveled woman has another episode of violent behavior and again, the couple does not see her. The neighbor returns. Now she doesn’t see the couple, but sees the disheveled woman. Her relationship to this woman is similar to her relationship with the other woman in the first couple’”but different. Now the neighbor seems more of a caretaker. Next, a loving, rather exuberant couple comes home, dressed in formal ware. The neighbor appears again, this time focusing on the new couple. Her relationship with this couple is similar’”but different’”from her relationship to the first couple.

Now all six characters are onstage at once. The pieces are in place, and you realize they are all the same characters’”but in three separate realities’”who have chosen very different roads in their lives. The women in the two couples and the single disheveled woman are all variations of Jesse, played by three actresses who don’t look particularly alike or unalike. The two husbands are Poppy’”a man we learn is quite ill’”and here the two actors look almost nothing alike. The neighbor, Mrs. Widkin, is played by the same actress in all the intersecting realities, and we realize that when Jesse is in her disheveled incarnation, she is mourning the recent suicide of Poppy’”which is why there are three versions of Jesse and only two of Poppy.

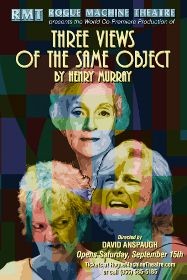

If any of this seems confusing here, it’s entirely down to me, since there is great clarity and purpose as the story unfolds onstage in Rogue Machine Theatre’s production of Henry Murray’s new play, Three Views of the Same Object. There is mystery, certainly, and that requires a bit of patience’”a quality sometimes lacking in those of us who scurry about multi-tasking ourselves into a fractured sense of what it means to actually focus, or think, or listen’”activities that take time’”and time is what fascinates Murray here. Time (and the lack thereof) is at the heart of these characters’ dilemmas; yet Murray is also quite concerned with how little time modern audiences have for narrative complexity. That led him to imagine a play where the surprises and intricacies of storytelling can all happen at once’”a kind of literary instant gratification.

The tone of the piece is every bit as exciting as the form. Murray’s language is matter-of-fact and smart’”never content with merely being clever. “You’re a china shop in a bull pasture,” is his kind of line; the wordplay is stylish and satisfying, but it cuts to the bone because of its authenticity and specificity.

The cast is remarkable. Anne Gee Byrd is a Los Angeles theater treasure, and her work here as the Jesse of the highball martini is sharp as a machete’”which makes her journey into self-pity and surrender as heartbreaking as it is inevitable. Nancy Linehan Charles tears into the character’s fury in a different way. If Byrd is enraged with the entire world, Charles plays it as a woman whose rage has turned inward’”deluging her with bitter hopelessness. K Callan’s version of Jesse is of a woman of grace, humor, and a keen ability to love who sees and accepts her own frailties. But what exactly does she gain from this self-awareness? All three views of this story come to a close without anything that could remotely be construed as a happy ending.

Allan Miller and Shelly Kurtz both bring qualities of pragmatism and a sense of mission to their respective views of Poppy. Miller is all regret and quiet acceptance, while Kurtz’”who plays the happier of the two versions’”gives Poppy more to lose, and thus, more to fear. Both actors shine in their parallel takes on very different kinds of despair. Kurtz’s Poppy despairs that his life with Jesse is almost over. Miller’s Poppy despairs that he is so ready for his life with Jesse to end.

Catherine Carlen brings real nuance and intelligence to her three variations on the same character. Small changes in her physicality speak volumes; she raises an eyebrow while essentially repeating the same line, and somehow, the meaning seems quite different. It’s not a showy role’”but Carlen’s is no less an accomplishment.

There is obvious symmetry to the fact that this play, with its three concurrent views of the same reality, has three directors: John Perrin Flynn, Brett Aune, and Hollace Starr. Yet I confess to feeling a certain dread at the thought of such a collaboration. Creating by committee is rarely satisfying; for the creative artist nor for the audience. I’ve no idea how these three worked on the piece; whether they rehearsed separately and then combined their efforts, or what, but this is a superbly fluid production; it is a single whole elegantly fractured, and whoever did whatever, the directors have formed a magnificent partnership.

Three Views of the Same Object is very much concerned with death, but it’s full of life and energy; muscular without being bulky; and it manages to be uplifting without a hint of treacle. And it’s a brilliant piece of theater. Any and all versions of me think so.

photos by John Flynn

Three Views of the Same Object

Rogue Machine Theatre

ends on November 4, 2012

for tickets, visit Rogue Machine

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Mr. Bernstein:

This is actually a fan letter. While I immensely appreciated your lovely review for our show, Three Views of the Same Object, I appreciated even more your clever writing. When my friends ask what the show is about, I point them to your review to not only answer that question, but as an example of just adorable writing.

Kudos!