GODS AND MONSTERS

Oedipus gets all the attention, what with his Freudian mixture of patricide and mommy love, but an arguably much more influential character in the Greek pantheon is the deeply confused Orestes. He didn’t fuck his mother Clytemnestra; he killed her’”and his act of (perhaps) justifiable homicide is woven into countless stories by some of biggies: Homer, Pindar, Sophocles, Euripides, Aeschylus, and Lucian, among others. Orestes’ murder of Clytemnestra is used to illustrate everything from the morally virtuous concept of mercy, to the terrible, awesome power of the gods, to the relative merits of misogyny, to the ultimate freewill that defines humanity, to the loyal wholesomeness of hot man-on-man action.

A whole tangled mess of murders and sexual indiscretions precedes Orestes’ birth, with that mess eventually overwhelming him and his monstrous family, the House of Atreus. They’re quite an assortment: Helen of Troy is his aunt; his uncle Menelaus is a morally bankrupt Trojan War hero and political hack; Orestes’ sister Electra is emotionally crippled, either by the murder of their father Agamemnon at the hands of their mother Clytemnestra (in revenge for Agamemnon killing their daughter Iphigenia, Orestes’ and Electra’s sister, at the behest of the goddess Artemis, who was pissed about her livestock getting eaten by Greek soldiers), or Electra might be going mad out of guilt over her incestuous relationship with Orestes, or it might just be that she’s petrified that she and Orestes will have to pay the price for their own crimes. Through it all, Orestes’ deepest connection seems to be with his studly BFF Pylades.

A whole tangled mess of murders and sexual indiscretions precedes Orestes’ birth, with that mess eventually overwhelming him and his monstrous family, the House of Atreus. They’re quite an assortment: Helen of Troy is his aunt; his uncle Menelaus is a morally bankrupt Trojan War hero and political hack; Orestes’ sister Electra is emotionally crippled, either by the murder of their father Agamemnon at the hands of their mother Clytemnestra (in revenge for Agamemnon killing their daughter Iphigenia, Orestes’ and Electra’s sister, at the behest of the goddess Artemis, who was pissed about her livestock getting eaten by Greek soldiers), or Electra might be going mad out of guilt over her incestuous relationship with Orestes, or it might just be that she’s petrified that she and Orestes will have to pay the price for their own crimes. Through it all, Orestes’ deepest connection seems to be with his studly BFF Pylades.

At the start of City Garage’s production of Orestes 3.0, Orestes is covered in blood, bedeviled by guilt, and hounded by the Furies’”a trio that is compelled by the gods to punish those guilty of familial impieties. He and his sister Electra have returned to Argos and must stand trial for the murder of their mother. Their ambitious uncle, Menalaus, is hypersensitive to public opinion (which trends firmly against Orestes and Electra) and he is unwilling to intervene. Under sentence of death, Orestes is persuaded by Pylades and Electra to kill Helen and kidnap her daughter Hermione’”also their niece, and unbeknownst to them (what a co-inky-dink!) will one day soon be Orestes’ wife. But before any more blood can be spilled, Apollo intervenes and forces everyone into something that passes for a happy ending’”in most Greek dramas, everyone who’s anyone ends up dead or with blood on their hands’”so anything short of mass murder counts as happy indeed.

At the start of City Garage’s production of Orestes 3.0, Orestes is covered in blood, bedeviled by guilt, and hounded by the Furies’”a trio that is compelled by the gods to punish those guilty of familial impieties. He and his sister Electra have returned to Argos and must stand trial for the murder of their mother. Their ambitious uncle, Menalaus, is hypersensitive to public opinion (which trends firmly against Orestes and Electra) and he is unwilling to intervene. Under sentence of death, Orestes is persuaded by Pylades and Electra to kill Helen and kidnap her daughter Hermione’”also their niece, and unbeknownst to them (what a co-inky-dink!) will one day soon be Orestes’ wife. But before any more blood can be spilled, Apollo intervenes and forces everyone into something that passes for a happy ending’”in most Greek dramas, everyone who’s anyone ends up dead or with blood on their hands’”so anything short of mass murder counts as happy indeed.

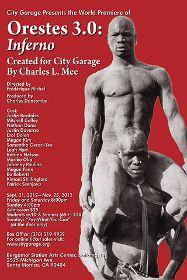

Depending on the author and the sensibilities involved, it’s a story that can seem ageless and classically relevant, or it can seem like an episode of Jerry Springer. In playwright Charles L. Mee’s new play Orestes 3.0: Inferno, there is a satisfying mixture of both. Directed by Frédérique Michel and produced by Charles Duncombe, it is a work of passion, intelligence, and mischief. There are some wobbly patches here and there, and a few of the performances wobble a bit as well, but Mee and Michel collaborate with graceful eclecticism as they seek to bring a modern sensibility to this ancient tragedy; employing music, dance, and a mélange of performance styles’”in an effectively utilized black box theater setting.

Depending on the author and the sensibilities involved, it’s a story that can seem ageless and classically relevant, or it can seem like an episode of Jerry Springer. In playwright Charles L. Mee’s new play Orestes 3.0: Inferno, there is a satisfying mixture of both. Directed by Frédérique Michel and produced by Charles Duncombe, it is a work of passion, intelligence, and mischief. There are some wobbly patches here and there, and a few of the performances wobble a bit as well, but Mee and Michel collaborate with graceful eclecticism as they seek to bring a modern sensibility to this ancient tragedy; employing music, dance, and a mélange of performance styles’”in an effectively utilized black box theater setting.

With any telling, retelling, or reimagining of Orestes, the whole thing rises or falls on the actor in the title role. Johanny Paulino has a lovely presence, and he is always believable and sympathetic’”perhaps a bit too sympathetic at times. Justified rage is a large part of what drives this character, and while there is a great deal of torment and desire on display, there’s not much ferocity. As Orestes’ hapless sister Electra, Megan Kim twirls in on point and never stops trying to keep her balance. Kim works hard, and her level of commitment is admirable, but I would like to see more colors. Her work is sometimes a bit flat in its hyper-intensity, with nowhere to go.

With any telling, retelling, or reimagining of Orestes, the whole thing rises or falls on the actor in the title role. Johanny Paulino has a lovely presence, and he is always believable and sympathetic’”perhaps a bit too sympathetic at times. Justified rage is a large part of what drives this character, and while there is a great deal of torment and desire on display, there’s not much ferocity. As Orestes’ hapless sister Electra, Megan Kim twirls in on point and never stops trying to keep her balance. Kim works hard, and her level of commitment is admirable, but I would like to see more colors. Her work is sometimes a bit flat in its hyper-intensity, with nowhere to go.

Helen of Troy is a standout. She is styled as a Hollywood glamor queen of the 1940s, followed around by slavish bellman who carry towers of wrapped boxes’”the spoils of her shop-til-you-drop exploits. Katrina Nelson is gorgeous and statuesque, with legs that go on and on forever and a stage presence to match. It’s not a role that calls for a lot of emotional range, but Nelson effortlessly snaps up everything she can from the material. I’m less enthralled by the devolution of her dialogue. Mee’s conception of Helen as a potty-mouthed nympho is funny, but as the narrative stakes mount, it gets less and less effective.

Helen of Troy is a standout. She is styled as a Hollywood glamor queen of the 1940s, followed around by slavish bellman who carry towers of wrapped boxes’”the spoils of her shop-til-you-drop exploits. Katrina Nelson is gorgeous and statuesque, with legs that go on and on forever and a stage presence to match. It’s not a role that calls for a lot of emotional range, but Nelson effortlessly snaps up everything she can from the material. I’m less enthralled by the devolution of her dialogue. Mee’s conception of Helen as a potty-mouthed nympho is funny, but as the narrative stakes mount, it gets less and less effective.

In his retooling of Menalaus, Mee seems to have channeled a bit of the slick, silver-tongued conman Billy Flynn from the musical Chicago. Darryl Keith Roach has a marvelous time as Menalaus, seducing any and all who cross his path, and he is a performer with a lot of power and range at his disposal, but he never really cuts loose completely. And the writing makes Menalaus seem less like a new take on a familiar character, than a pastiche of other showbiz archetypes.

In his retooling of Menalaus, Mee seems to have channeled a bit of the slick, silver-tongued conman Billy Flynn from the musical Chicago. Darryl Keith Roach has a marvelous time as Menalaus, seducing any and all who cross his path, and he is a performer with a lot of power and range at his disposal, but he never really cuts loose completely. And the writing makes Menalaus seem less like a new take on a familiar character, than a pastiche of other showbiz archetypes.

There’s a lot of movement here and Michel directs her actors with evident authority and imagination. One of my favorite bits is when the furies use their smart phones as up-lighting while they wheel around office chairs upon which sit their impossible high-heeled shoes. Their intended instruments of transport (the shoes) are themselves in need of transport, since none of the girls can really walk anywhere in them. It’s clever, fresh, and feels inspired.

Less effective for me are moments that feel more like what I imagine off-off-Broadway must have been in the 1960s and 70s’”a lot of in-your-face sexual posturing that isn’t nearly as shocking anymore, where saying the words “vagina” and “penis” is meant to be cutting edge. It isn’t. Passages that are meant to feel shockingly alive sometimes feel more like sophomoric digressions.

Less effective for me are moments that feel more like what I imagine off-off-Broadway must have been in the 1960s and 70s’”a lot of in-your-face sexual posturing that isn’t nearly as shocking anymore, where saying the words “vagina” and “penis” is meant to be cutting edge. It isn’t. Passages that are meant to feel shockingly alive sometimes feel more like sophomoric digressions.

If there is one true misfire here, it is Mee’s rendering of Apollo, performed with coy artificiality by Erol Dolen. I’ve no doubt that Dolen is doing what is asked of him when he makes Apollo into an impish, self-satisfied bore’”but it’s an idea that I just don’t get. Apollo comes across as something more like the naughty, playful Hermes, or the wine-soaked party boy Dionysus, which makes his actions feel even that much more arbitrary, even by the standards of Greek gods. And it points up the trouble modern audiences can sometimes have with Greek drama. The undeniable importance of the gods can be maddening. We are the bratty children, whining, “But why?!” And the gods are our exhausted parents, snapping back, “Because we said so!”

photos by Paul M. Rubinstein

Orestes 3.0: Inferno

Gity Garage at Bergamot Station Arts Center in Santa Monica (Los Angeles Theater)

through November 25, 2012

for tickets, visit http://www.citygarage.org