AN AMUSING TRIFLE

A.R. Gurney’s entertaining, dynamic but trivial new play Heresy reinvents the story of Jesus Christ (in the play he’s called Chris), changing the setting from 33 A.D. Jerusalem to America in the not-so-distant future. Jim Simpson’s solid direction, engaging performances, clever dialogue, well-articulated ideas and an abundance of jokes manage to distract one from the play’s lack of drama and its confused logic, as well as the fact that the ideas it expresses so well are all rehashed dull liberal slogans; for those disdainful of intellectual masturbation, there are a number of eye-rolling moments.

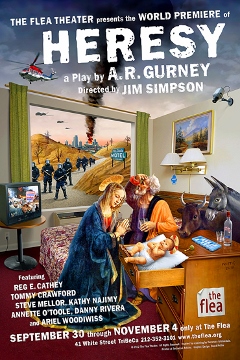

Joseph (Steve Mellor) and Mary (Annette O’Toole) come to the office of their old friend, the Homeland Security prefect Pontius Pilot (played with adroitness and charm by Reg E. Cathey), to inquire as to the whereabouts of their son Chris, who had been arrested a few weeks earlier and is now lost in the bureaucracy of America’s internal security apparatus. The minutes of this meeting are recorded by Pontius’s orderly Mark (Tommy Crawford), who changes and embellishes them, hoping to one day write a book. In the course of Pontius’s investigation and decision-making process we meet his materialistic wife Phillis (made charismatic by Kathy Najimy’s layered performance), Chris’s friend and college roommate Pedro (Danny Rivra), and Lena (Ariel Woodiwiss), a prostitute who is also Chris’s lover.

Heresy begins as a satire of the paranoid right-wing imperialistic forces in America; Pontius’s military uniform is reminiscent of that of an SS officer (costumes by Claudia Brown). In this version of the country’s future, prisoners are held in secret, incommunicado, and are routinely subjected to “enhanced interrogation.†Chris is one such prisoner and the only character ever in jeopardy in Mr. Gurney’s play. Though we never meet him, at the beginning at least, his fate concerns us, both in the abstract and as it affects his family and friends. Unfortunately, this thematic line and the potential for drama it offers are dispensed with early on, and whatever dangers Chris faces at the start of the play are basically neutralized about twenty minutes in. At that point Heresy becomes a polemic against materialism, consumerism, and religious, political and social dogmas.

Subsequent threats to Chris’s life are introduced; Pedro reveals that he was the one who had his friend arrested in order to protect him from violent fanatical individuals and organization that he fears would kill Chris for spreading his liberal message. But this threat, besides being vague and uncertain, is also not dealt with logically or meaningfully by the characters, causing whatever initial tension and suspense there was to evaporate.

For the most part the ideas expressed in Heresy are sound, its observations accurate. Unfortunately they are also old, obvious and dull; much of the dialogue feels like an excuse for Mr. Gurney to tell us what he thinks are the shortcomings of modern American society. Regrettably we see no dramatic examples of how these social failings hurt and destroy people and cultures. Perhaps the biggest thematic weakness of the play is in its portrayal of Chris (the Christ character) as merely an intelligent liberal activist-agitator, neglecting the most profound ideas Jesus embodies: spirituality and love. There is one powerful line in the play, the very last one, which resonates. But in view of the profound subject matter, one line is not nearly enough.

Set Design by Kate Foster; Lighting Design by Brian Aldous; Sound Design by Jeremy S. Bloom

poster design by David Prittie

photos by Hunter Canning

Heresy

The Flea Theater, 20 Thomas St. in TriBeCa/SoHo

ends on November 4, 2012

for tickets, call 212.226.2407 or visit The Flea