RED AND BROWN IS THEATRICAL GOLD

Los Angeles is usually the last major theater city in the states to see productions of playwrights whose works have received praise in their world premieres, either in New York or at a regional house. It often takes years for exhilarating plays to arrive in what is the busiest theater city nationwide. Playwrights whose works have been presented in storefront and mid-size houses (Annie Baker and Amy Herzog come to mind) in Chicago, San Francisco, San Diego, et al, don’t see the light of day in L. A. for eons, if at all. According to artistic directors I have spoken to, the reason why Los Angeles is often the last man out is that literary agents, whose job it is to generate buzz from a scribe’s first few productions, will not release the rights to L. A. companies.

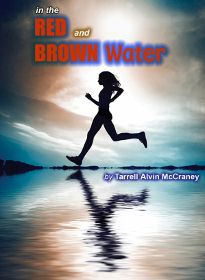

Interpret this as you will, but if The Fountain Theatre’s glorious, thrilling, and first-class Los Angeles premiere of In the Red and Brown Water were a benchmark for Los Angeles theater, these agents would be beating down our doors. With Shirley Jo Finney at the helm, and one of the best ensembles in years, the work of the most exciting playwright of his generation has finally arrived in the City of Angels four years after it premiered in Atlanta.

The playwright is Tarell Alvin McCraney, with whom I first became acquainted when San Francisco’s A.C.T. staged his Marcus, or the Smell of Sweet two years ago. I wrote of the young African-American writer, “It is thrilling to hear the poetic dialogue of a propitious new American playwright for the first time; one who uses a unique, innovative, and visionary arrangement of words that not only awaken your senses, but heighten your hopes that the profligate use of technological blather will not drown out a voice which is at once rich, challenging, and distinctive.” Marcus is the final installment of McCraney’s triptych, The Brother/Sister Plays, which includes In the Red and Brown Water and The Brothers Size’”all three utilize some of the same characters, but the plays stand on their own. (The Brothers Size will play at San Diego’s The Old Globe beginning January, 2013.)

While the stories are fictional, the trilogy’”which takes place in “the distant present” in the mythological town of San Pere, Louisiana (think New Orleans)’”has a base in the urban struggles from McCraney’s youth as a gay man in Miami, a third world country to him. He has converted his history’”a brother’s incarceration and a drug-addicted mother who died from AIDS’”into these plays, in which you will also find elements, among others, of Greek drama, August Wilson, Lorca, and Williams (the latter two are most apparent in both McCraney’s poetic language and his themes of sexuality).

Water concerns a young, beautiful runner named Oya who turns down a scholarship so that she may attend to her ailing Mama Mojo, who encourages her daughter’s dreams but discourages any entwinement with a snake of a man named Shango. Oya wants urgently to make her mark on the world, but once her opportunities begin to dwindle, the choices she does make stem from desperation, leading a blossoming woman and her promising career into a shadowy realm of troubled uncertainty.

First and foremost, McCraney is a storyteller who is interested in arousing the senses of his audience more than showing off his ear for poetry. To tell his tale, the playwright uses an emotionally authentic but heightened and rhythmic style of dialogue, which draws from Miami’s Liberty City neighborhood where he grew up, a mix of African-American, Caribbean, and West African cultures. In particular, it is the Yoruba people of West Africa that are the mortar of The Brother/Sister Plays: Yoruba culture, as contained in this play, consists of chanting, singing, dancing, folk/cultural philosophy, religion, and folktales (McCraney’s characters are named after Yoruba deities). This is why Water is current yet eternal, personal yet universal. And while all but one of the characters are people of color, the play’s themes of self-discovery, choices, and destiny transcend race. McCraney is not just a voice for all people, but for the ages.

At the center is Oya, who, at times of great stress or revelation, gasps for air as if she is drowning in the murky waters of young adulthood. But it is Diarra Kilpatrick who will have you breathless as she vacillates from wide-eyed innocence to tragic self-realization. Physically fit and vigorous, the beautiful Ms. Kilpatrick calls forth incorruptibility with such effortless grace that when rage suddenly emits from the ravishing actress, it startles like a crime against nature.

Once Mama Mojo (a crafty Peggy A. Blow) leaves our beloved Oya, the rogue Shango returns; although he is a serpent in Oya’s Garden of Eden, we always welcome back the wicked cad because Gilbert Glenn Brown slides into the scene like oil on water, turning a horny rascal into a loveable corruptor’”as Mama says, “Some of the nastiest things come wrapped like that.” Shango’s competition arrives via the stuttering Ogun (an irresistibly sweet Dorian Christian Baucum), who truly loves Oya, but may not have what it takes to get much more than pity from her.

A candy-addicted adolescent named Elegba (a tender and vulnerable Theodore Perkins) is haunted by dreams he cannot interpret and visits Oya’s home often; while he has a strong need to connect with his community, his petty thievery hints that he is more likely haunted by his own lack of self-control. It is the “grey” (read: bisexual) Elegba who will sire the “sweet” (read: gay) Marcus’”but that’s another play hopefully to be staged soon’¦by Ms. Finney’¦at the Fountain.

Other denizens of San Pere include the nosy but insightful Aunt Elegua (a sensuous and sassy Iona Morris), the gossipy troublemakers Nia and Shun (the colorful Maya Lynne Robinson and Simone Missick), a sympathetic school coach (Stephen Marshall), and a sexed-up DJ at a local club (Justin Chu Cary).

The realism and rich life of the ensemble will no doubt have spectators feeling as if they are eavesdropping on their neighbors, but the greatest connector between the viewer and the storytellers comes courtesy of Mr. McCraney, who has his characters speak stage directions: “Shango enters,” “Heavy breath,” “Oya bows her head,” and “Legba enters like the moon during the day, there but not saying anything.” As a result, our sensations are intensified, and we are part of the story, thereby freed up to examine our own choices as we stumble through life.

As in the plays of one of McCraney’s influences, August Wilson, the word “nigga” is bandied about, but it has never sounded less offensive. It is part of the patois of housing projects such as this one in San Pere, used to amplify words such as “fool,” “friend,” and “brother.” The poetic usage of the word elucidates that “nigga” is neutral, it’s the meaning we attach to it which is not. (Side bar: One of McCraney’s inspirations for writing Marcus was the profound absence of gay characters in Wilson’s oeuvre.)

As in the plays of one of McCraney’s influences, August Wilson, the word “nigga” is bandied about, but it has never sounded less offensive. It is part of the patois of housing projects such as this one in San Pere, used to amplify words such as “fool,” “friend,” and “brother.” The poetic usage of the word elucidates that “nigga” is neutral, it’s the meaning we attach to it which is not. (Side bar: One of McCraney’s inspirations for writing Marcus was the profound absence of gay characters in Wilson’s oeuvre.)

Another reason to see this production now is that The Brother/Sister Plays are far better-suited for an intimate space. Soon enough, McCraney will mature even more, and his works will be staged in unsuitable venues (even this glorious production would be swallowed up at the likes of The Ahmanson). It’s also sad that Los Angeles doesn’t have an ensemble regional theater with the integrity, clout, and backing of Steppenwolf in Chicago’”one which attracts and nurtures theater practitioners such as McCraney, who officially became the company’s 43rd ensemble member in April, 2010.

McCraney may have arrived late to Los Angeles, but the Fountain Theatre has ensured that his work demands the attendance of all who have been yearning for the next great American playwright.

photos by Ed Krieger

In the Red and Brown Water

Fountain Theatre

scheduled to end on December 16, 2012 EXTENDED to February 24, 2013

for tickets, call 323.663.1525 or visit http://www.FountainTheatre.com