DISHONET ABE

Historical movies are often made as historical parallel. They comment on our time as much as their time. On some level this is the inevitable nature of history – taking from the past what is necessary to explain the present.

Historical parallel clearly seems to be the intention of Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln, which is a comment on our era as much as a comment on 1865: The inexperienced politician from Illinois tries to do the right thing amid a deeply divided nation. Lincoln focuses on a very short time frame in Abraham Lincoln’s presidency – the noble legislative fight for a constitutional amendment to end slavery toward the end of the Civil War. With this intense focus, Lincoln carries an underlying message from an ardent Obama supporter to today’s Chief Executive – to do what is right even if it is meets the opposition of the moment.

The weakness is that Lincoln engages in one of Spielberg’s pet emotional deceits – stacking the deck. In slavery, Lincoln is fighting an inarguable and overwhelming moral evil. There’s no modern way to disagree with the cause. The problems of today are financial, and therefore more tangled. So the question must be asked of Lincoln is whether it’s an accurate and functional parallel to the problems the country now faces. Or are our problems of today far less sinister, with far more variables and more uncertain outcomes?

Lincoln also misses another angle: Are the actions portrayed in Lincoln as righteous as they seem, without a double-edge to the sword? What Tony Kushner’s script does do especially well is document both Lincoln as a wily politician and Washington as a political sausage factory. Lincoln isn’t bothered by the need to bribe House members for votes. He lies and passes a stovetop hat filled with patronage and other political goodies in pursuit of what he sees as an unquestionable moral good. The movie could just as easily be titled Dishonest Abe.

As film, Lincoln has at least two-and-a-half weaknesses. John Williams’ score becomes the overbearing nightmare that we fear when we see the name John Williams. Janusz Kaminski’s cinematography, all spangles of ghostly light flowing through dark chambers, is another. The images are lovely on the surface, but they mythologize Lincoln while the rest of the film de-mythologizes him. Tony Kushner’s uneven script is a half-problem. It is brilliant when defining the presidential character and captures Lincoln’s ability to rule those around him by anecdote, but there is a struggle with how to supply the audience with backstory: There’s likely a more elegant way to do this than having Mary Todd Lincoln (Sally Field) run off her entire contentious history with Republican giant Thaddeus Stevens in a White House reception line.

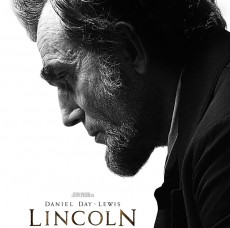

A majority of the aforementioned gripes are exonerated by the brilliance of Daniel Day-Lewis’ performance, portraying Lincoln gentle in manner, two steps ahead in intelligence, and determined to wrestle something worthwhile and lasting out of the nightmare of war. It makes him a slick politician, a loving but suffering husband, and a distant father. While Spielberg and Kushner miss the mark on an attempt at historical parallel, what they do best is to humanize the man on the five-dollar bill.

photos courtesy of Dreamworks Pictures and 20th Century Fox

Lincoln

Amblin Entertainment, Dreamworks Pictures, and 20th Century Fox

rated PG-13

in wide release November 16, 2012