UNFULFILLED WANTS

David Mamet’s latest dramatic work, The Anarchist, begins as abruptly as it ends, but despite the jarring effects, there is a good reason for the sharpness of these moments. Jeff Croiter’s lighting cues punctuate the first and final scenes like black and white markers for what is otherwise grey, nebulous and “opaque” material, the latter word often uttered by prisoner Cathy (Patti Lupone) during her conversation with her jailer, Ann (Debra Winger). But the lack of clarity is not derived from the insightful and clever way in which Mamet crafts his play. Rather, it is the complex characters and multi-layered plot that make it hard to figure everything out, and purposefully so. Yet, while Mamet does not err on the side of writing, his stilted and stunted direction of the show leaves much to be desired.

Set in what is vaguely described as “an office,” The Anarchist deals wholly with unfulfilled wants and wants that maybe should have been left unexplored. The latter ushers in this 2-character drama. Once again, Cathy, a woman imprisoned some 35 years ago for being rightfully convicted of murder during a bank robbery, is appealing to Ann, the woman who sent her to jail, for her release. This latest plea comes right before Ann vacates her position. As is customary for plays penned by Mamet, the characters engage in verbal hockey, swatting each other back and forth with questions and terse answers with increasing velocity for the first 20-minutes. From henceforward, the pace of the dialogue eases up and is intermittently interrupted by phone calls made to Ann.

Set in what is vaguely described as “an office,” The Anarchist deals wholly with unfulfilled wants and wants that maybe should have been left unexplored. The latter ushers in this 2-character drama. Once again, Cathy, a woman imprisoned some 35 years ago for being rightfully convicted of murder during a bank robbery, is appealing to Ann, the woman who sent her to jail, for her release. This latest plea comes right before Ann vacates her position. As is customary for plays penned by Mamet, the characters engage in verbal hockey, swatting each other back and forth with questions and terse answers with increasing velocity for the first 20-minutes. From henceforward, the pace of the dialogue eases up and is intermittently interrupted by phone calls made to Ann.

Through their exchange, it is revealed that much of this conversation has been regurgitated before, but for the latest and greatest news: Patty has found Jesus, and is urgently requesting a release not only to continue the good work that she has started while in prison, but to also steer the direction of her father’s dying soul. The problem? Despite an A+ for effort and good behavior, Ann does not believe in Patty’s conversion. Inmates have used this defense time and time again, and because Patty gunned down police officers after they begged for their lives and seemed to enjoy it, Anne’s just not buying it.

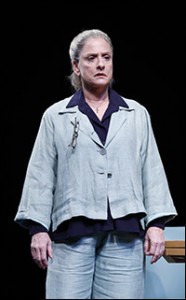

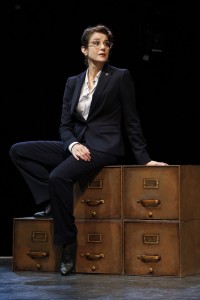

In addition to the anarchy, another subject where Ann and Patty play a mean tug-o-war is sexuality and gender. Neither women are characterized specifically as lesbian, but Patty admittedly has had several relationships with women while Ann openly discusses female attraction, even if restrainedly so. Patty accuses Ann of being jealous of her sexual exploits, and if words aren’t enough, Patrizia Von Brandenstein creates a cell block with Ann’s appearance while Patty is the picture of carefree. While both ladies don pant suits, Patty’s look is relaxed and casual, with her hair in a ponytail and shoulders ever round. Ann, on the other hand, looks uptight in a fussy, overwrought updo and stiff, uncomfortable and unwomanly posture. As the chatting continues, the tables are turned to where it is now Patty offering freedom to Ann; the freedom that she has found in Christ. Despite the cross around Ann’s neck, Patty insists that her study of Ann over the years has revealed that Ann is miserable and lacking faith. All of a sudden, The Anarchist becomes a “help me, and I’ll help you” situation, but who can know the truth?

In addition to the anarchy, another subject where Ann and Patty play a mean tug-o-war is sexuality and gender. Neither women are characterized specifically as lesbian, but Patty admittedly has had several relationships with women while Ann openly discusses female attraction, even if restrainedly so. Patty accuses Ann of being jealous of her sexual exploits, and if words aren’t enough, Patrizia Von Brandenstein creates a cell block with Ann’s appearance while Patty is the picture of carefree. While both ladies don pant suits, Patty’s look is relaxed and casual, with her hair in a ponytail and shoulders ever round. Ann, on the other hand, looks uptight in a fussy, overwrought updo and stiff, uncomfortable and unwomanly posture. As the chatting continues, the tables are turned to where it is now Patty offering freedom to Ann; the freedom that she has found in Christ. Despite the cross around Ann’s neck, Patty insists that her study of Ann over the years has revealed that Ann is miserable and lacking faith. All of a sudden, The Anarchist becomes a “help me, and I’ll help you” situation, but who can know the truth?

Based on Von Brandenstein’s set design, no one. To demonstrate what is going on between and inside of the characters, the stage background is colored grey and is coarse to the touch. To complement the emotions and positions even further, the simple furniture are in neutral and washed out shades of grey, light blues and natural colors.

Whereas all of the other production elements seem to be united in their depiction of obscurity, Mamet’s direction is peculiar for the wrong reasons. Mamet creates a lot of blank space between the characters, adding a dimension of difference between the two actors that does not enhance this piece. Though not in a jail cell, the two formidable and celebrated actors appear confined to a certain radius, deterring them from what may have been more dynamic performances.

Whereas all of the other production elements seem to be united in their depiction of obscurity, Mamet’s direction is peculiar for the wrong reasons. Mamet creates a lot of blank space between the characters, adding a dimension of difference between the two actors that does not enhance this piece. Though not in a jail cell, the two formidable and celebrated actors appear confined to a certain radius, deterring them from what may have been more dynamic performances.

At a mere 70 minutes, The Anarchist does not give you a lot of time to consider the arguments. However, since Mamet does stuff the allotted time with a lot of talk as well as an overzealous decorator would stuff an apartment, you won’t feel like the running time is cut short. The Anarchist is dense with sex, politics, religion, ethics and philosophy without being flashy, and it’s a good thing because those elements don’t need flash. It’s just too bad that the direction does.

photos by Joan Marcus

The Anarchist

John Golden Theatre in New York City

scheduled to end on December 16th, 2012

for tickets, call 212-947-8844 or visit The Anarchist