MOLIÈRE FOR DUMMIES

Attend David Ives’ The School for Lies’”a manic contemporary travesty’”if you want to fully appreciate Molière’s 1666 masterpiece The Misanthrope, as serious a comedy as the 17th century farceur ever attempted. Brashly brilliant, grotesquely scatological, industriously low-brow, and perversely wrong-headed, this Midwest premiere of The School for Lies at Chicago Shakespeare Theater’s Courtyard Mainstage takes Molière’s bittersweet look at one man’s doomed quest for moral purity and perpetrates a punch-drunk, gag-reflex-ridden, toxically sarcastic, and woefully inadequate “translaptation.”

Crude and comically hip, David Ives wants to seek “the play underneath the words,” to strip The Misanthrope of the past and to create a comedy fitted to our modern follies, as if Molière’s universality is some kind of lodestone. The irony is that Ives’ modernization is instantly contradicted: The set and costumes are straight out of Versailles’ golden age, while the hyper-dialogue teems with enough product-placing anachronisms to give this new play a short shelf life: It should be unplayable within the decade.

Ives believes that his “Molière” is just what our trolling, anonymous-libeling, litigious, and plastically phony culture deserves. Sadly, that’s all the more reason to miss The School for Lies and stick with The Misanthrope. Molière looked beyond the shallow fops, smug toadies, rancid gossips, and corrupt careerists of Louis XIV’s sunny state. His “stage of fools” held a mirror to its audience. Above all, he never stooped to the blatant or obvious: He knew that our best traits are sickeningly interwoven with our worst.

In his tragicomedy, Molière contrasts the title character Alceste, a fearless opponent of pious or poetic cant and unearned entitlement, with Celimene, the flirtatious, scandal-speaking soubrette whom Alceste has woefully loved because opposites attract. He defends her merry mischief-making even as he loathes it. He’s the last to desert her when her hypocritical backbiting scares off all other suitors. But he too can’t abide the double-dealing. Alceste exiles himself from lying humanity. He runs off to a tropical isle. The pathos here is that Celimene finally treasures Alceste when it’s too late, while he loses his last hope for cherishing humanity when he misreads her late-blooming respect.

Ives doggedly ignores the depths behind Molière’s satire. He sticks to the surface, turning these supposedly courtly and often philosophical characters into foul-mouthed windbags, X-rated exhibitionists, and fashion zombies.

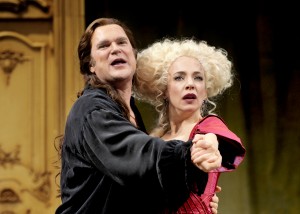

In Barbara Gaines’ sadly faithful staging, Deborah Hays’ sprightly Celimene is a born user, only interested in Alceste because she credulously believes he’s the king’s bastard brother and can help defend her against a suit for slander. (She’s too self-obsessed to even recognize that Alceste, here called “Frank,” is indeed someone completely different, a person she should know like her fan.) There’s no love here, only a bit less loathing. Ben Carlson’s bellowing “Frank” manages to entice Celimene’s idiotic cousin Eliante (Heidi Kettenring as a Baroque bimbo) and the prudish and ancient coquette Arsinoe (Judith-Marie Bergan mired in a thankless and typically sexist caricature).

Meanwhile, Frank’s confidant Philinte (rubber-faced Sean Fortunato)’”to Molière, a raisonneur who provides the play’s antidotes to the dysfunctional lovers’ extremes’”is reduced to a puerile attachment to Eliante, the greatest victim of Ives’ misogyny. Worse, in the increasingly incoherent second act, Fortunato endures a very unfortunate drag turn in which he impersonates the Queen of France and banishes Celimene’s predatory worshippers to the stupidity (Kevin Gudahl as Acaste), twerpiness (Paul Slade Smith as Clitander), and vacuity (Greg Vinkler as Oronte) they’ve earned so well. (Strangely, these buffoons, with their clueless and commedia-like fatuousness, deliver the most Molière-like imitations.)

No question, this bottom-feeding, too-clever-for-its-own-good parody and its Rococo raunch offers Gaines’ superb cast delicious chances to offend whatever sensibilities a modern audience dares to preserve. But Molière had bigger fish to fry than to turn bathroom-stall graffiti into dialogue. He skewered a worthier target’”the human weaknesses that are too strong’”hypocrisy, calumny, spite, revenge and, above all, misplaced love. The joke wasn’t on us’”the paltry payoff that Ives pursues’”it is us. Molière used a pen. Ives settles for spray paint.

Even more unfortunately, Ives, who can’t replicate Molière’s wit but never met an expletive-crammed insult he couldn’t use, relies for humor on forced feminine rhymes and singularly stupid sight gags. The worst is the wretched running joke in which a servant (an increasingly frantic Samuel Taylor) keeps having his canapé tray upset by Ives’ selfish and inconsiderate triflers. The result can only be called “Molière Meets Benny Hill.”

The cleverest ingredients in this sorry spectacle are Susan E. Mickey’s savagely mocking 17th century fashions and Daniel Ostling’s ugly, spiderweb-like chandelier. It threatens to squash the parasites below. But it can never match the deflation that Ives inflicts on the master Molière.

photos by Liz Lauren

The School for Lies

Chicago Shakespeare Theater; Courtyard Mainstage at Navy Pier

scheduled to end on January 20, 2013

for tickets call 312-595-5600 or visit http://www.chicagoshakes.com/school

for info on this and other Chicago Theater, visit http://www.TheatreinChicago.com

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

I am also a critic. Often, when we review plays, we forget that our job should be to analyze the product that is placed on the stage for not only our likes or dislikes, but in fact, will our readers get a bang for their entertainment buck. Those who like slapstick comedy and really don’t know diddly about the original work, will have a ball at CST. Yes, the purist will not enjoy what they see, but isn’t it a critic’s job to clarify this and say what we see as well as feel and not take the word “critic” that seriously. I respectfully ask Mr. Bommer to lighten up.

Al,

You want to protect the ignorance of an audience so they can enjoy a show for all it’s not. Sorry but that’s not something that critics are responsible for–quite the contrary. I want to judge this rancid raunch as it is and argue that it could have been so much more–if Ives didn’t try to kill vaudeville all over again. Laughter isn’t the true test of a play. It’s the shock of recognition, and, unlike Moliere, it doesn’t happen here. “Bangs for the buck”–how appropriate that is for this show…

The real misanthrope here is David Ives. He reduces all the characters to ninnies, zombies, zanies or toadies–a plague on all their houses. If only he’d been honest enough to pass it off as his own and spare Moliere any guilt by association. I loved Ives’ ALL IN THE TIMING and I might have been amused by THE SCHOOL FOR LIES if it weren’t so true to its title, if it didn’t batten off of a better author.

He calls it an “adaptation” of Moliere. But it’s just a merry mess, lacking anything like a coherent plot, believable characters or a moral center, just a lot of foul-mouthed one-liners spouted by actors who deserve better. In fact it’s the exact opposite of the work he says is his source and that will outlast this tripe by as many centuries as separate us from 1666. Critics should not create their own “house of lies” trying to defend Ives’.

Larry, your review is right on target! I am sorry that I did not read it before arranging a night out. Thank you for an honest appraisal.